How Trump’s nominee will affect abortion, prisons, affirmative action, and gay rights.

Barring a major surprise in the Senate, Brett Kavanaugh will be taking a seat on the Supreme Court this fall.

He will be replacing Anthony Kennedy who has, since at least 2005, been the swing vote on many of the Court’s most ideologically charged decisions, responsible for 5-4 rulings that legalized same-sex marriage, preserved Roe v. Wade, upheld warrantless wiretapping, blew up campaign finance restrictions, overturned DC’s handgun ban, and weakened the Voting Rights Act. That position has made him one of the most powerful people in America for well over a decade now, not even counting the 18 years he shared his position as the Court’s swing voter with Sandra Day O’Connor.

The new median justice will be Chief Justice John Roberts, a mostly reliable conservative who has proven remarkably willing to overturn decades-old precedents.

With Kennedy gone and Kavanaugh in his place, the Court’s decisions on issues where Kennedy has been a down-the-line conservative — like campaign finance and corruption, most business regulation and voting cases, gun rights, religious liberty, etc. — likely won’t change. There’s already a 5-4 conservative majority on those, so conservative rulings like the ones Kennedy wrote or joined in DC v. Heller, Citizens United, or Hobby Lobby will continue apace.

What will change are rulings on issues where Kennedy has helped maintain a shaky 5-4 center-left consensus and where Kavanaugh absolutely will not. Because of the Court’s longstanding principle of stare decisis, or obeying past precedent barring a compelling reason not to do so, some liberal Court achievements are likely to stay. But a Court without Kennedy and with Kavanaugh is substantially more likely to:

- Overturn Roe v. Wade and allow states (and maybe the federal government too) to ban most or all abortions.

- Reject challenges to capital punishment and solitary confinement.

- Rule in favor of religious challenges to anti-discrimination law, and perhaps, in an extreme case, reverse some past Supreme Court rulings on gay rights.

- Bar government actors from engaging in explicit race-based affirmative action.

And there are likely to be more aftershocks that are hard to anticipate this far in advance.

An America after Anthony Kennedy and under Brett Kavanaugh looks significantly different from America before. The movement against mass incarceration could run into unprecedented resistance from the Court, and the anti-abortion movement could notch its greatest victories in a half-century.

This Supreme Court vacancy will give Donald Trump the power to shift jurisprudence on a range of critical issues. It could wind up being the most important part of his legacy.

Abortion under Kavanaugh

Nothing is guaranteed, but Kavanaugh will be much likelier to join a decision overturning Roe v. Wade and giving states the ability to ban abortions as early as the first trimester.

This may take years after Kavanaugh’s confirmation; a state would need to pass a law clearly incompatible with the Court’s existing approach to abortion rights and wait for the challenge to reach the Supreme Court before the new justice would have a chance to join a ruling. The anti-abortion movement might choose a more cautious strategy, instead chipping away at Roe with measures that fall short of outright bans. But with Kennedy gone, the votes for an outright reversal of Roe would probably be there.

It’s clear that Kavanaugh believes Roe was wrongly decided. In a speech last year to the American Enterprise Institute, Kavanaugh praised then-Associate Justice William Rehnquist’s dissent in Roe at length, saying that Rehnquist’s jurisprudence on substantive due process issues (the constitutional theory that enabled the ruling for abortion rights in Roe) “help[ed] to ensure that the Court operates more as a court of law and less as an institution of social policy,” even if Rehnquist didn’t succeed in preventing the majority decision in Roe or in overturning it.

Kavanaugh has also, as a federal judge, attempted to prevent a 17-year-old unauthorized immigrant from receiving an abortion, writing once his efforts were rebuffed by the full DC Circuit that the court had created “a new right for unlawful immigrant minors in U.S. Government detention to obtain immediate abortion on demand.” Such a right, he wrote, did not and should not exist.

Alex Wong/Getty Images

Alex Wong/Getty ImagesKavanaugh is not the pivotal justice on Roe, however; that would be John Roberts, who in 1990 wrote a brief arguing that Roe was “wrongly decided and should be overruled.” But Roberts has nonetheless acted as chief justice to preserve laws he clearly has trouble with constitutionally (like Obamacare) for the sake of the court’s legitimacy. Roe could be the same.

Then again, his gradual efforts to roll back the Voting Rights Act and public-sector unions, by contrast, are an example of his willingness to rock the boat to get a conservative outcome, as Irin Carmon details in the Washington Post. Maybe he’ll attempt the same strategy on abortion.

You can go back and forth on where Roberts will land seemingly forever. William Saletan at Slate has a piece making the case that Roe will survive, while UC Irvine constitutional law professor Leah Litman argues it’s done for.

But it’s worth asking what overturning Roe will look like if the Court does go that direction. There are two broad ways it could happen. The first is the overturn-without-overturning approach. The second is a full-on reversal.

Kavanaugh has, in the unauthorized immigrant minor case, already suggested what an overturn-without-overturning approach could look like. Not to be too hyperbolic, but he argued that literally keeping a girl in detention to keep her from getting an abortion was not an undue burden on her right to an abortion. That might seem implausible (it certainly did to the rest of the DC Circuit), but it offers a pathway to allowing other extreme restrictions on abortion rights.

The 20-week abortion bans adopted by 21 states haven’t reached the Supreme Court yet. The Ninth Circuit overturned Arizona and Idaho’s bans, only for the Supreme Court to decline to hear an appeal. Under Roe, abortion bans before viability (or about 24 weeks) are generally unacceptable. But Kavanaugh and the court’s other conservatives could weaken that standard by taking up a 20-week ban and judging it to not be an undue burden on abortion rights.

After that, a state could attempt a ban on abortions after a heartbeat is detected (generally at week six of a pregnancy). That would be a dramatic escalation, but building on the 20-week decision, the conservatives could judge it to not be an undue burden. After Roe has been duly chipped away at, an outright reversal would look more plausible.

But it’s also possible the Supreme Court will hear a case about an outright ban before it has time to gradually weaken Roe. As Carmon notes, states have been adopting a wide array of abortion restrictions, from ones that clearly violate Roe and would set up an outright challenge to it, to ones that could be upheld without junking Roe and Casey entirely.

Mississippi recently approved a 15-week abortion ban (already blocked in federal court); Kentucky passed a ban applying to dilation-and-evacuation abortions after 11 weeks and Ohio and South Carolina are weighing “total prohibitions.” Just this past May, Iowa adopted a law banning abortions after fetal heartbeats, which again, usually occur at six weeks of pregnancy.

The passage of heartbeat bans or total bans on abortion at the state level will almost certainly lead federal appeals courts to overturn them, and if the conservatives on the Supreme Court don’t want to fully overturn yet, they can simply decline to hear the case.

But a conservative Court of Appeals panel could rogue and decide to disobey Roe and Casey. (This would most likely happen after the post-Kavanaugh Court allows some less dramatic regulations like a 20-week ban to go forward, after which the circuit judges could argue that Roe and Casey no longer apply in the wake of more recent Supreme Court jurisprudence.) Then the Supreme Court would likely be forced to take up the issue.

This is what happened in 2014 to 2015 with same-sex marriage: Circuit courts split on the issue, forcing the Supreme Court to resolve the disagreement.

That eventuality would bring the possibility of overturning Roe entirely to the Court’s door, and it would have little choice but to hear the case. After that point, all bets are off.

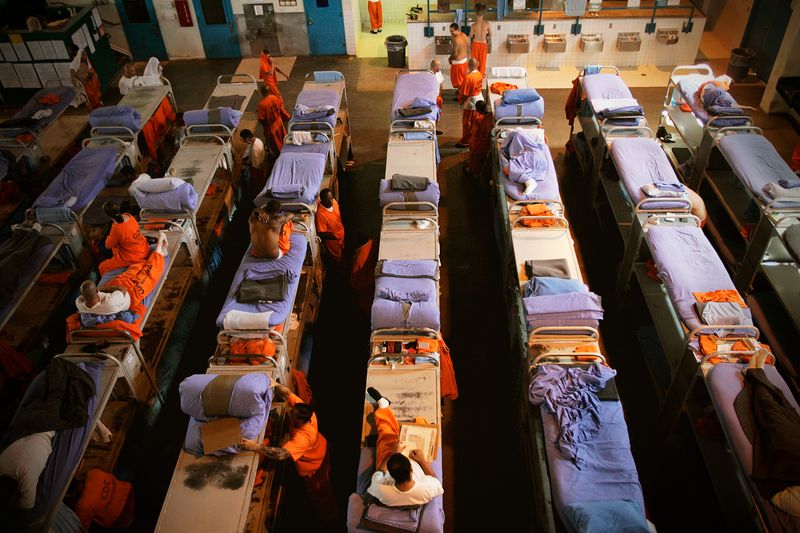

Prisons and the death penalty in America under Kavanaugh

Currently, with Kennedy, there appears to be a five-justice majority on the Supreme Court for sharply limiting solitary confinement in America. With Kavanaugh in Kennedy’s place, that majority has evaporated, likely replaced with a harder-line majority that could preserve the practice.

In 2015, Anthony Kennedy filed a concurring opinion in Davis v. Ayala, a death-penalty case in which the Court (joined by Kennedy) sided against the defendant. Nevertheless, Kennedy used his concurrence to unleash a bracing jeremiad against the evils of solitary confinement, in which the defendant had been held for most of his 25-plus years in prison.

”Research still confirms what this Court suggested over a century ago: Years on end of near-total isolation exact a terrible price,” Kennedy wrote. “In a case that presented the issue, the judiciary may be required, within its proper jurisdiction and authority, to determine whether workable alternative systems for long-term confinement exist, and, if so, whether a correctional system should be required to adopt them.”

Bebeto Matthews/AP

Bebeto Matthews/APThe implication was clear: Kennedy wanted advocates to bring a case challenging the constitutionality of long-term solitary confinement on the grounds that it constitutes cruel and unusual punishment under the Eighth Amendment. He basically dared them to, and suggested that if such a case reached the Court, he’d be inclined to limit the practice.

Sharon Dolovich, a law professor at UCLA and faculty director of the university’s Prison Law & Policy Program, told me in 2016 that solitary confinement was the “one major unresolved issue” in criminal justice “that is definitely going to come up” in the next few years.

It’s a long time coming. At any given moment, about 80,000 to 100,000 people are held in solitary confinement in the US; in many states, the average stint in solitary lasts years. And it’s been that way at least since the 1980s, without any federal court intervention to halt it.

”There’s so much data now — physiological data, psychological data, reentry data — there’s so much data making clear the extended physical, psychological, and emotional trauma that people suffer in extended solitary confinement, it would be so easy for the Court just to point to it all and conclude there’s an objective harm,” Dolovich said.

Jonathan Simon, a law professor and director of the Center for the Study of Law and Society at UC Berkeley, also speaking in 2016, told me that solitary confinement is on “the verge of being found unconstitutional, at least in its most excessive forms.” Just what “excessive” means there is, naturally, a matter of debate, and Simon cautions that the Court could err on the side of giving prisons too much leeway.

He noted that Ashker v. Brown, a recent case challenging solitary confinement in California that ended in a settlement rather than reaching the Supreme Court, “involved a class of inmates that had been held more than 10 years, and the settlement will still allow people to be held up to five years, and even after that they can still be held in solitary if they’re given programming and special services.” By contrast, the United Nations special rapporteur on torture has called for an absolute ban on solitary confinement lasting 15 days or more. “I’m not sure Kennedy or any justice would go nearly that far,” Simon says.

But without Kennedy on the Court, a ruling going even as far as a five-year maximum becomes less likely.

Solitary confinement is not the only case where a more conservative justice could make a difference. In 2011, Kennedy wrote a 5-4 decision upholding a lower court order mandating that California release tens of thousands of prisoners to reduce overcrowding, which the state itself admitted was unconstitutional. It was, Simon told me, “the first prisoners’ rights decision to come down in favor of the prisoner in a long time. It ended mass incarceration in California.”

Kennedy was also the best hope that opponents of capital punishment had for a ruling against the practice, even though he’s often sided with conservatives in past death penalty cases on the constitutionality of, say, using a particular lethal injection method.

Back in 2016, Simon told me that he was “somewhat optimistic” that Kennedy would join with Breyer and Ginsburg (who have already declared their belief that capital punishment is across-the-board unconstitutional), Sotomayor, and Kagan in an anti-death penalty case. “The reason … goes back to his interest in dignity,” Simon said. “The strongest of the opinions in Furman” — the 1972 case that briefly abolished capital punishment — “was William Brennan’s, and Brennan based it most directly on human dignity. He argued the Eighth Amendment bans any punishment you can’t carry out without respecting the dignity of those being punished.”

Kennedy leaned heavily on the importance of dignity in Brown v. Plata, the California prison overcrowding case. Simon even found an early Kennedy opinion from when he was a circuit court judge in the 1970s in which he quoted Brennan’s concurrence in Furman at length.

Even if Kennedy didn’t buy a dignity argument for abolishing the death penalty, Simon said he thought Kennedy would be swayed by the issue of delays, which Breyer raised in his 2015 anti-capital punishment dissent. Legal delays were the entire reason for the prisoner’s stay in solitary confinement that Kennedy assailed in his concurrence last year.

Gary Friedman/Los Angeles Times via Getty Images

Gary Friedman/Los Angeles Times via Getty Images”[Kennedy] came and gave a talk at Berkeley Law about a year and a half ago, and one of my colleagues was rude enough to ask him point blank whether he thought the death penalty was compatible with human dignity,” Simon told me. “Of course he declined to answer, but he said kind of cryptically, ‘Here in California you guys take so long enough to execute people that we may not even need to reach that cliff.’”

This is all moot now that Kennedy is gone, sure to be replaced by a more doctrinaire supporter of capital punishment.

Having him off the bench will also prevent incremental steps against capital punishment from going forward. In 2008, Kennedy wrote for a 5-4 liberal majority that it was unconstitutional to impose the death penalty on people convicted merely of rape, not murder.

The status quo is especially likely to hold given the records of Kavanaugh and of Roberts, the new median justice. According to SCOTUSBlog’s Edith Roberts, Kavanaugh has “tended to rule against defendants” in criminal cases; he lacks much of a record on capital punishment and solitary confinement, however.

Roberts has vocally defended lethal injection from the bench and declined to join Kennedy’s anti-solitary confinement concurrence. He has shown occasional glimmers of a willingness to limit the death penalty and life imprisonment, when juvenile defendants and racially biased witnesses are involved, but in general is a much more hostile figure for opponents of mass incarceration and capital punishment than Kennedy has been.

Affirmative action in America under Kavanaugh

Anthony Kennedy is hardly an uncritical supporter of affirmative action in public employment, education admissions, or other realms.

In 2003, he dissented in Grutter v. Bollinger, a case in which O’Connor and the Court’s liberals ruled that the University of Michigan Law School’s racial affirmative action system was constitutional, and not an unconstitutional quota system. In 2007’s Parents Involved in Community Schools v. Seattle School District No. 1, he was the swing vote behind a ruling holding that Seattle, Washington, and Louisville, Kentucky’s voluntary desegregation programs were unconstitutional.

In 2009’s Ricci v. DeStefano, he ruled that New Haven, Connecticut’s Fire Department discriminated against white applicants for promotions. He wrote the controlling opinion in 2014’s Schuette v. Coalition to Defend Affirmative Action, which upheld Michigan’s ban on affirmative action.

But he is not an implacable foe of the practice, either. In his Grutter dissent, he echoed Justice Lewis Powell, who held Kennedy’s seat before him and wrote the controlling opinion in Regents of the University of California v. Bakke, a 1978 case in which the Court held that affirmative action was constitutional but explicit quotas (“16 of the 100 students must be black”) went too far.

“There is no constitutional objection to the goal of considering race as one modest factor among many others to achieve diversity, but an educational institution must ensure, through sufficient procedures, that each applicant receives individual consideration and that race does not become a predominant factor in the admissions decision-making,” Kennedy wrote in the Grutter dissent.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThis position of his became additionally relevant with 2016’s Fisher v. University of Texas, in which he wrote a majority opinion defending the University of Texas’s use of race in admissions. With Fisher, he effectively became the one vote holding together the Court’s majority defending affirmative action in at least some cases.

A more stalwart conservative in Kavanaugh now takes Kennedy’s place. In 1999, Kavanaugh wrote an amicus brief for the anti-affirmative action Center for Equal Opportunity arguing that Hawaii’s law only allowing Native Hawaiians to vote for officials of the Office of Hawaiian Affairs was unconstitutional (the Supreme Court agreed). The Court agreed, 7-2, but the fact that Kavanaugh teamed up with the Center is a strong indication of his views on affirmative action more broadly.

After a Kennedy-for-Kavanaugh swap, it’s likely that the uneasy affirmative action consensus will buckle, and a ruling finally doing away with public affirmative action programs will come.

Gay rights in America under Kavanaugh

Arguably, Kennedy’s greatest legacy on the Court — and certainly what he hopes will be his greatest legacy — are his decisions expanding the scope of LGBTQ rights.

In 1996’s Romer v. Evans, he authored the Court’s first major pro-gay rights decision, invoking the 14th Amendment’s Equal Protection Clause in striking down a Colorado state constitutional amendment that prevented cities and towns from adopting their own bans on discrimination against gays, lesbians, or bisexuals.

Seven years later, in 2003’s Lawrence v. Texas, Kennedy wrote a 6-3 decision invalidating Texas’s ban on oral and anal sex between two men or two women. That decision overrode 1986’s Bowers v. Hardwick, a decision upholding Georgia’s sodomy law. In Lawrence, Kennedy tellingly did not use equal protection reasoning but instead found that any bans on consensual sexual behavior between adults, regardless of the genders involved, violate the due process clause’s guarantee of personal liberty. (This was similar to the reasoning the Court had used in Roe and to invalidate bans on contraception in Griswold v. Connecticut.)

A decade later, in 2013, Kennedy wrote the 5-4 decision in United States v. Windsor overturning the federal Defense of Marriage Act on equal protection grounds. The decision required the federal government to respect and honor same-sex marriages at the state level, while still allowing states to ban same-sex marriage if they wished. And two years after that, in 2015’s Obergefell v. Hodges, he swept away bans on same-sex marriage altogether, ending with a stirring tribute to the value of marriage that’s become a mainstay of wedding readings in the years since:

No union is more profound than marriage, for it embodies the highest ideals of love, fidelity, devotion, sacrifice, and family. In forming a marital union, two people become something greater than once they were. As some of the petitioners in these cases demonstrate, marriage embodies a love that may endure even past death. It would misunderstand these men and women to say they disrespect the idea of marriage. Their plea is that they do respect it, respect it so deeply that they seek to find its fulfillment for themselves. Their hope is not to be condemned to live in loneliness, excluded from one of civilization’s oldest institutions. They ask for equal dignity in the eyes of the law. The Constitution grants them that right.

Mark Wilson/Getty Images

Mark Wilson/Getty ImagesIt is fair, then, for gay rights advocates to worry about what could happen to the Obergefell precedent now that Kennedy has retired and will be replaced by Kavanaugh, who is opposed by every LGBT rights group you can imagine.

There are certainly some conservatives on the Court who are interested in chipping away at the ruling’s guarantees. Gorsuch, Thomas, and Alito in 2017 dissented from a ruling requiring Arkansas to list same-sex parents on their children’s birth certificates, arguing that to do so does not violate Obergefell. That, Slate’s Mark Joseph Stern argued, set the stage for a legal strategy based on gradually chipping away at the right to marriage until it’s practically worthless.

“[John] Roberts would be free to rewrite Windsor and Obergefell however he wants,” Stern writes. “Roberts could remain faithful to the original text of both decisions. He could also reverse them. But the likeliest possibility is that Roberts first cuts them down to a single guarantee—the right for same-sex couples to receive a marriage license with no attendant privileges. In case after case, Roberts could vote to allow discrimination against same-sex couples but affirm their right to the license itself.”

The trouble with this argument is that we don’t actually know where Roberts stands on the precedential value of Obergefell. He didn’t register a dissent in the Arkansas case the way his conservative colleagues did; it’s possible he dissented without letting that dissent be recorded, but it’s also possible he sided with the liberals.

Moreover, majorities of Americans in 44 of the 50 states now support same-sex marriage. The overwhelming public opinion shift in favor of marriage equality might make Roberts more hesitant to chip away at the right, and it also might deny the Court opportunities to take up the issue, if the popularity of same-sex marriage prevents states from trying to restrict the right in ways that would be challenged and make it to the Court.

My hunch is that LGBTQ rights are the part of Kennedy’s legacy least likely to be sacrificed once he’s gone. But certainly a Court without Kennedy, and with Kavanaugh, will be less friendly to LGBTQ causes than one with Kennedy still around.

Read More

https://cdn.vox-cdn.com/community_logos/52517/voxv.png