China’s new security law just went into effect in Hong Kong. Free speech evaporated overnight.

At 11pm local time on Tuesday, Hong Kong’s government unveiled the text of a draconian new national security law that gives the Chinese government vast new powers to crackdown on free speech and dissent in Hong Kong.

Drafted in secrecy by top Chinese officials in Beijing — and not seen by the public until that very moment — the law criminalizes “secession, subversion, organization and perpetration of terrorist activities, and collusion with a foreign country or with external elements to endanger national security.”

Those who commit such acts — which experts say are vaguely defined in the law, and thus allow for an extremely broad interpretation by authorities — face severe punishment, up to and including life in prison.

“The things that you talk about, you write about, you publish about, and even the people you know about, that you have connection with, can be potentially at risk of being prosecuted under this law,” Ho-Fung Hung, a political economy professor at Johns Hopkins University who focuses on China and East Asia, told Vox.

And, according to the New York Times, “The law opens the way for defendants in important cases to stand trial before courts in mainland China, where convictions are usually assured and penalties are often harsh.”

The law went into effect immediately. Less than 24 hours later, Hong Kong police announced the first arrest under the new policy.

And they weren’t subtle about it: They immediately posted photos on their official Twitter account of the young man they’d arrested. His alleged offense? Holding a pro-Hong Kong independence flag.

#BREAKING: A man was arrested for holding a #HKIndependence flag in #CausewayBay, Hong Kong, violating the #NationalSecurityLaw. This is the first arrest made since the law has come into force. pic.twitter.com/C0ezm3SGDm

— Hong Kong Police Force (@hkpoliceforce) July 1, 2020

Chinese state media quickly reported the story of the first arrest — but they made sure to blur out the offending images of the pro-independence flag itself, lest they commit the same grievous act of promoting such a seditious idea (something the Hong Kong Police Force apparently didn’t think to do before tweeting the photos).

CGTN appears to have rectified the HKPF’s tweet through the magic of pixelation https://t.co/syCh9Vy1i5

— David Moll (@moll_david) July 1, 2020

For many Hong Kong watchers, these images marked the beginning of the end of the freedoms that Hong Kong, unlike the rest of mainland China, had enjoyed for decades.

The law effectively ends “one country, one system”

The “one country, two systems” principle — enshrined in the Basic Law, Hong Kong’s de facto constitution — has been in place ever since Britain handed back control of the territory to China in 1997.

As Vox’s Jen Kirby explains, “The ‘one country’ part means [Hong Hong] is officially part of China, while the ‘two systems’ part gives it a degree of autonomy, including rights like freedom of the press that are absent in mainland China. China is supposed to abide by this arrangement until 2047, but it has been eroding those freedoms and trying to bring Hong Kong more tightly under its control for years.” Kirby continues:

Last spring, Hong Kong’s legislature tried to pass an extradition bill that critics feared would allow the Chinese government to arbitrarily detain Hongkongers. That ignited massive protests, leading to months of unrest that sometimes turned violent. The bill was withdrawn, but the demonstrations continued, as the fight transformed into a larger battle to protect Hong Kong’s democratic institutions.

But Beijing’s imposition of this new national security law is the most direct and dramatic move China has made toward erasing those freedoms once and for all.

“[The National Security Law] is a complete destruction of the rule of law in Hong Kong and threatens every aspect of freedom the people of Hong Kong enjoyed under the international human rights standards or the Basic Law,” Lee Cheuk Yan, a veteran Hong Kong politician and activist, told US lawmakers during a House Foreign Affairs Committee hearing on the new law on Wednesday.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/20062949/GettyImages_1223717145.jpg) Anthony Wallace/AFP via Getty Images

Anthony Wallace/AFP via Getty ImagesAnd Bonnie Glaser, director of the China Power Project at the Center for Strategic and International Studies think tank, told Vox, “This law really eliminates ‘one country, two systems.’”

But Hong Kong’s pro-democracy activists aren’t cowed — or at least, not yet

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/20063027/GettyImages_1223468732.jpg) Anthony Kwan/Getty Images

Anthony Kwan/Getty ImagesOn Wednesday, Hong Kong Chief Executive Carrie Lam held a press conference to announce the new law — a law drafted without her input and whose full details even she didn’t know until just the day before.

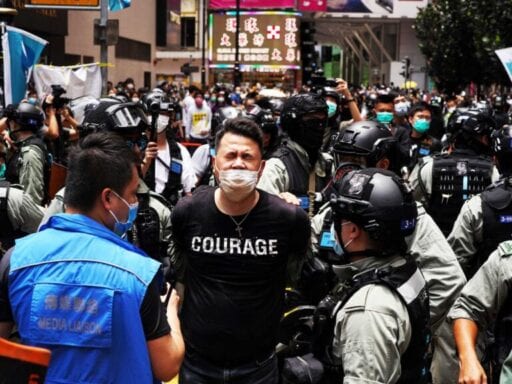

Outside, thousands of Hongkongers took to the streets to protest against — and in direct defiance of — it, despite a heavy police presence.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/20062905/GettyImages_1223718458.jpg) STR/AFP via Getty Images

STR/AFP via Getty Images/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/20062967/GettyImages_1223723438.jpg) Anthony Kwan/Getty Images

Anthony Kwan/Getty ImagesRiot police deployed around the city held up large purple banners that read: “This is a police warning. You are displaying flags or banners / chanting slogans / or conducting yourselves with an intent such as secession or subversion, which may constitute offenses under the ‘HKSAR National Security Law.’ You may be arrested and prosecuted.”

By the end of the day, nearly 400 people had been arrested, including 10 who were specifically arrested for violating the new law.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/20062930/GettyImages_1223720160.jpg) Anthony Kwan/Getty Images

Anthony Kwan/Getty Images/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/20062832/GettyImages_1223719853.jpg) Dale de la Rey/AFP via Getty Images

Dale de la Rey/AFP via Getty ImagesBut experts fear that despite this initial strong opposition, the law’s chilling effect will happen eventually.

“People will be intimidated. They will charge people and they will sentence them,” Glaser said. “The Chinese have this saying, ‘kill the chicken to scare the monkey.’ They will look for very early cases that they can prosecute so that they can demonstrate their resolve in the hope of intimidating other people from challenging their authority.”

Johns Hopkins’s Hung also said the law could have major implications for September’s Hong Kong legislative elections, because the Chinese government could use the new law as a legal basis to suppress pro-democracy candidates.

“Under the new law, many of the slogans, many of the opinions are going to be illegal,” Hung said.

There’s already precedent for Chinese election officials intervening in Hong Kong’s legislative elections — in 2016, a number of candidates were disqualified for allegedly supporting Hong Kong independence, Hung said.

“I think that the Chinese were nervous after the last round of the district elections that there could be many Democrats who would be elected and, potentially, the pro-China legislature would lose legislators,” Glaser said.

“I think that if candidates do not moderate what they say, that they will be prevented from running under the law,” Glaser added. “They could easily be arrested.”

In fact, that has already happened: one pro-democracy lawmaker, the Democratic Party’s Andrew Wan, was arrested during the protests Wednesday.

It’s a stark example of just how quickly life has changed in Hong Kong, literally overnight.

Author: Jennifer Williams

Read More