Netflix’s biggest and most troubling edit to the show, for which the platform created a new English-language translation and voice track, dials back its famous homoerotic subtext. The late-series love expressed between the main character, Shinji, and his close friend Kaworu, seems to have been inexplicably reframed as a less overtly romantic kind of friendship — to the extent that in some scenes, the word “love” has been replaced with more euphemistic words. Given that the boys’ relationship is an important turning point for the series and its feature film continuations, it’s a strange choice, and one that has alienated many fans.

There are other differences to the show that longtime viewers have taken issue with — most notably the removal of the series’ famous ending theme, variants of the classic jazz standard “Fly Me to the Moon,” due to licensing issues. But a long, systemic tradition of queer erasure has prompted the most vocal fans to criticize the Netflix translation for seemingly diminishing what they call the series’ previously unambiguous queerness. And that has only stoked debate about why that queer reading of the original series wasn’t seen as the most accurate one in the first place. (I’ve reached out to Netflix for comment.)

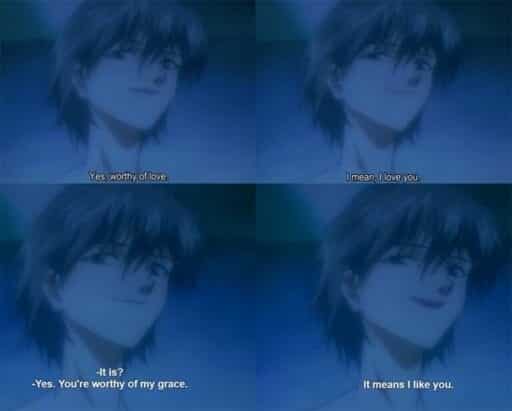

The new Netflix translation waters down the homoerotic nature of one of the series’ significant relationships

Neon Genesis Evangelion, a.k.a. Eva, is a dark, complex anime series that spends a lot of time focusing on sexual exploration and the development of sexual and romantic relationships. That makes it particularly significant that the hero Shinji has a close friendship with another boy, Kaworu, who openly declares his love for him.

Or at least he used to. Now, 24 years after Eva first debuted in 1995, the new, official Netflix translation of the anime has significantly altered some of Kaworu and Shinji’s most famous interactions to be less, well, gay. Below is a comparison between the original English translation of the series from the ’90s, originally released by the Japanese studio Gainax, and Netflix’s version, illustrating the type of translation shift that fans are particularly unhappy about. The top row is the original translation, followed by Netflix’s new version on the second row.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/16448009/kaworu.jpg) Gainax; Netflix

Gainax; NetflixThis translation change is not only emotionally meaningful but dramatically so. Later on, Shinji remarks that this is the first time anyone has told him they love him. In the new version, however, this remark carries a completely different kind of emotional weight. See below — the Netflix translation is in the right column; the original translation is in the left:

sorry but this is not ok (right is from the new netflix eva script) pic.twitter.com/LehJYFjMng

— Jimmy Gnome (@jimmygnome9) June 21, 2019

Translator Dan Kanemitsu worked with Studio Khara, the studio that Eva’s creator Hideaki Anno created in 2006 and that produces the modern-retelling feature film series inspired by the anime, on the new translation for Netflix. In a Twitter thread, he responded to one fan’s questions about the scene, first noting that he couldn’t speak to translation decisions made about the “I love you” scene in particular, before adding that he wanted to keep the scene’s meaning open to “interpretation.”

While I am not in a position to refer specifically to the decision involved in the scene you described, in all my translation of any title, I have tried my best to be faithful to the original source material. Bar none.

— 兼光ダニエル真 (@dankanemitsu) June 21, 2019

It is one thing for characters to confess their love. It is quite another for the audience to infer affection and leave them guessing. How committed are the characters? What possible misunderstandings might be talking place? Leaving room for interpretation make things exciting.

— 兼光ダニエル真 (@dankanemitsu) June 21, 2019

Kanemitsu’s responses quickly garnered plenty of fan criticism. Some argued that the new translation of these lines was nowhere close to their literal reading; others pointed out that this drastically shifts the narrative weight of their relationship.

In an email, Kanemitsu asserted that while he can’t discuss the decision-making that went into this scene, “It is not my intention to marginalize queer relations in media, as I have fought hard to ensure free speech should cover queer relations in manga and this material should be made available to the largest audience possible.” Referencing a 2010 Tokyo ordinance designed to restrict access to sexually explicit manga and other material, he noted, “I pointed out the hypocrisy of the laws that was being designed specifically to restrict manga and anime that featured relationships between same sex couples.”

But the very existence of laws like the ones Kanemitsu is referencing is more reason not to water down the translation, fans protest. Insisting that hints of queer relationships be kept ambiguous has been done for decades to erase acknowledgment of queer identity and queer relationships from media narratives. “This may be true of storytelling in general,” wrote one fan in a lengthy thread responding to Kanemitsu, “but it ignores what LGBT media consumers, esp. anime fans, have been dealing with their whole lives.”

Above all, fans of the series argue that the decision to take this action now is as troubling as it is puzzling, given that Eva and its themes have been well known for nearly 25 years. Throughout that time, Kaworu’s textual love for Shinji, and the tension between them, has been coded as queer.

This relationship has been queer for a quarter-century

Between 1994 and 2013, manga writer/artist Yoshiyuki Sadamoto published the Neon Genesis Evangelion manga, which both adapts and expands upon the series. The Evangelion manga, which originally began appearing in Japan before the anime series even aired, was intended to be an official companion to the anime. While it does not serve as the source text for the anime, the manga is widely considered to be a very good synthesis and expansion of the Eva storyline. And although there are some differences in plot between the two, the manga is frequently discussed and analyzed in conjunction with the anime and films.

In 2006, Sadamoto published the 67th chapter of the manga, later collected in the series’ 10th volume; in it, Kaworu’s sexual interest in Shinji becomes explicit in a scene where Kaworu repeatedly kisses Shinji and then shares his romantic feelings for him. This scene is visually sexualized:

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/16448031/Screen_Shot_2019_06_21_at_7.47.11_PM.png) Viz Manga

Viz Manga“How does it feel when a person comes to like another person?” Kaworu asks in the official English translation of this scene (the manga was published in the US by Viz). “Wanting to touch them. Wanting to kiss them. Not wanting to lose them.”

Shinji then rejects Kaworu with some good old-fashioned gay panic:

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/16448034/Screen_Shot_2019_06_21_at_7.40.49_PM.png) Viz Manga

Viz MangaLater on, however, in chapter 75 of the manga, Shinji admits that he was “attracted to” Kaworu all along, even though “a guy shouldn’t like another guy like that.”

Sadamoto wasn’t just inventing this attraction as a new twist in their relationship. The homoerotic nature of Kaworu and Shinji’s bond has been well established since the series first aired, and has been present throughout later installments in the franchise.

In 1997, a pair of companion books about Evangelion, featuring interviews with creator Anno, were released in Japan. One of the books, Hideaki Anno Parano Neon Genesis Evangelion, opens with a section of character descriptions, one of which describes Kaworu’s relationship to Shinji. I contacted four people fluent in Japanese, including a native Japanese speaker, who all translated this passage in the same way: “To Shinji, Kaworu was the first friend he could open up to, and he could also be someone that could be a same-sex partner.” The key phrase “same-sex partner” also translates to “same-sex lover” and “someone he could love romantically.” Each of the people I spoke to was adamant that there is no room for interpretation in this paragraph.

This is a section of the book that is separate from Anno’s interviews, and perhaps was written by its editor, Kentaro Takekuma, and not taken from Anno himself. But the inclusion of this reference to the love between the two characters makes it clear, at least, that an explicitly queer reading of the characters was officially on the radar as early as 1997.

In his email, however, Kanemitsu noted that Anno makes no reference to the characters’ sexuality in the interviews that appear in the two books. He shared with us quotes from Anno, taken from the other companion book. (Vox has verified Kanemitsu’s translation.) In that book, Hideaki Anno Schizo Neon Genesis Evangelion, Anno repeats several times in his interview that the series is meant to be ambiguous, something of “a Rorschach test.” As translated by Kanemitsu in his email, one passage in particular implies that Anno intended for everything to be up for debate:

Anno: [Eva is a work] where the remaining process [of completing the work] is in the hands of the audience. I place strong emphasis in that relationship. After you get to a certain point, I want them to make their own judgment. There are portions where things are left ambiguous, so it all depends on how you view [and judge it for yourself.] I think the character of the person [e.g. a personality] reveals itself in that process. [Eva is a work] where if ten people watch it, not all of the ten will [compliment] it. In that sense, it’s very Japanese.

“Please do not interpret this as a defense on the [Netflix] translation,” Kanemitsu told me, “but rather, an argument of what makes Evangelion so wonderful and compelling for people of so many walks of life.”

Kanemitsu thus invites the question: If everything is up for debate, how do we arrive at clear and meaningful translations?

Translation work requires nuanced decision-making that isn’t always clear. But de-gaying the characters shouldn’t be part of the process.

The relationship between Kaworu and Shinji isn’t the only thing that’s been updated in the new release — nor the only difference that’s caused fans to side-eye the new version. For example, in one of the series’ darkest (and most spoiler-laden) moments, a character’s intense declaration that “I’m so fucked up” has become “I’m the lowest of the low.” And while this is a more literal translation of the original Japanese, many fans argue that the new line doesn’t carry nearly the impact of the original version.

Overall, Netflix’s subtitling has hewed more closely to a literal interpretation of the original Japanese — though that makes the liberties taken with a word as easy to translate as “love” seem all the stranger in comparison.

To make a little more sense of how all this interconnects, I reached out to Narelle Bailey, an anime localization editor based out of Melbourne, Australia, who’s been a fan of Eva since its original release. Localization editors work with English-language translations of anime to make them more culturally relevant to viewers in different regions outside of Japan. Bailey told me she’s always trying to consider the broader and historical context of the texts she edits.

“I definitely try to think of things like, how does this fit with what has come before it in terms of tone and intent,” she said. “Sometimes I’ll ask the translator questions to clarify the exact layers on a certain term or phrase. For a show as big and important as Evangelion, I’d like to think they were thinking about this. It’s really gonna come down to the individual team involved, and their process and how much freedom they have.”

As a queer anime fan, Bailey was upset by the changes to the new Netflix release of Eva; still, she gave me a bit of insight into what the thought process might have been like. Eva is a deeply religious show, full of symbols drawn from Judeo-Christian tradition, so Bailey suggested that the translators might have wanted to make the relationship between Kaworu and Shinji more connected to those themes — which could be how we get the phrase “worthy of love” being converted to the far more confusing “worthy of my grace.”

“Arguably, they felt that the religious themes made the most narrative sense. Kaworu is speaking in an encompassing, Christ-like way, which is fine!” she told me. “But the ‘love’ part is still essential when taken in concert with the themes of the show, with what Shinji has been through, and with the intense way [the plot develops].”

Bailey scoffed at Kanemitsu’s argument that the relationship needed to be left up to interpretation. “‘I love you’ is already ambiguous enough in the context of this show,” she said. “There’s a reason people have found ways to argue against the nature of this relationship and its feelings for 20 years.” The nature of queer fictional relationships is such that even if what’s presented textually can be read as overtly romantic, she explained, society tends to insist on the least queer reading possible.

But the word love is hugely significant to the plot, she said. “This teenage boy, who’s been through the emotional wringer and has never been offered an uncomplicated pure scrap of affection in his whole life, is told in no uncertain terms, with no ambiguity, that he is deserving of love, and is thus loved. Whether you want to deny the queer/romantic reading or not, the ‘love’ part is important narratively and thematically.”

Because fans already are often framed derisively as being obsessed with romantic relationships, it may be easy to minimize their legitimate anger over the changes. “I hate that this will be framed as ‘shipping’ nonsense most of all, when Shinji’s experiences of love and affection and relationships with others are so much what the show is about,” Bailey told me.

She observed that it wouldn’t be difficult at all for Netflix to quickly re-subtitle the track to change the textual translation. However, the dubbed voiceover, she speculated, would be harder to amend. And it’s possible that due to the many moving parts of Netflix itself, any questions translators and localization editors might have for the creator would remain unanswered. In a typical translation scenario, “at least myself or a translator can pose a question for clarification to the original publisher or rights holder,” she noted. But because Netflix most likely works with third-party studios and distributors like Anno’s Studio Khara, outsourcing elements like the audio and language tracks, this kind of direct communication would likely never happen.

Still, she added, “Honestly, did nobody working on the show look at its history … and go, hey, this is gonna ruffle feathers?!”

But while many fans were annoyed with Netflix, others were frustrated that the conversation was overshadowing other important aspects of the rerelease. One writer pointed out that Netflix had cast a nonbinary actor, Casey Mongillo, in the lead role of Shinji, but this laudable move had virtually gone unnoticed amid the more widespread outcry over the other changes that had been made.

I would very much like to just be excited and intrigued about a trans actor being cast as Shinji but WELL HERE’S ALL THIS OTHER BULLSHIT I GUESS

— ㋐ Vrai Kaiser ㋐ (@WriterVrai) June 21, 2019

Toward the end of the day, I was chatting with a friend of mine, a longtime geek culture journalist, about the experience of going to bed excited for the long-awaited release of the series and waking up to a maelstrom of backlash. Pragmatically, she reminded me that Eva has been a series mired in controversy since its debut two decades ago.

“Everyone has always been mad about Evangelion,” she said, sounding weary. “This is the way of the world.”

Author: Aja Romano

Read More