More people than ever say they’re feeling pressured to look and be the best. It’s taking a toll.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/15986155/Vox_The_Highlight_Logo_wide.jpg)

In fifth grade, Hailey Magee rushed home from school distraught and crying after seeing that she’d received an A-minus on her first letter grade report card. Growing up, she had learned that the way to receive validation and love from family members and teachers was to be a high achiever. So to Magee, that A-minus felt like a failure.

“I was shattered,” she said. “In that moment, I felt like my self-worth as a human had fallen far below what it would have been if I’d gotten an A or an A-plus.”

Magee turning a good grade into an example of her inferiority is a textbook example of a growing trend in recent years: perfectionist behavior. Paul Hewitt, a clinical psychologist and professor at the University of British Columbia who studies the phenomenon, remembers a bright young college student who came to him, similarly obsessed with earning an A+ in one of those ridiculously difficult courses that are designed to weed out people who aren’t serious about a major. By the end of the term, he told Hewitt he was having suicidal thoughts. “I got the A+, but all it did was demonstrate to me that if I was really smart I wouldn’t have had to work so hard to get it,” he said.

Perfectionism is a broad personality style characterized by a hypercritical relationship with one’s self, said Hewitt, who co-authored Perfectionism: A Relational Approach to Conceptualization, Assessment, and Treatment. Setting high standards and aiming for excellence can be positive traits, but perfectionism is dysfunctional, Hewitt said, because it’s underscored by a person’s sense of themselves as permanently flawed or defective. “One way they try to correct that is by being perfect,” Hewitt said.

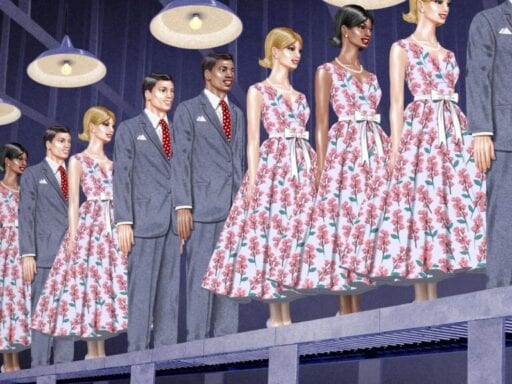

Once an issue that affected a select few, perfectionism is now a growing cultural phenomenon, fueled by modern parenting and social media and an increasingly competitive economy, researchers say. Struggles with perfectionism have been the subject of multiple TED talks, Instagram memes, Oprah discussions, and books. Even celebrities such as Demi Lovato, Zendaya, and Natasha Lyonne are opening up about their battles with perfectionism.

“We are so sucked into our screens, and our life is so perfectly curated,” Netflix star Lana Condor said in an episode of the “Hi Anxiety” video series about mental health. “You see other perfect lives and your life isn’t like that. And so if I go out, and people see that my life isn’t perfect, I’m afraid they’ll judge me.”

Look around these days, and you can find perfectionism “everywhere,” said Thomas Curran, a psychologist at the University of Bath. “I see it in my own friends and colleagues and the students I teach.” In an age where social media makes it possible to constantly compare your own life to others, perfectionism has only become amplified.

Curran and his colleague Andrew Hill gathered data from more than 40,000 college students who had taken a psychological measure of perfectionism between 1989 and 2016. In 1989, about nine percent of respondents posted high scores in socially prescribed perfectionism, but by the end of the study, that had doubled to about 18 percent, he says. “On average, young people are more perfectionistic than they used to be,” Hill says, and “the belief that other people expect you to be perfect has increased the most.”

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19414447/GettyImages_1151695913t.jpg) Robyn Beck/AFP via Getty Images

Robyn Beck/AFP via Getty ImagesThe rise in perfectionism is especially troubling because it has been linked to an array of mental health issues — a meta-analysis of 284 studies found that high levels of perfectionism were correlated with depression, anxiety, eating disorders, deliberate self-harm and obsessive-compulsive disorder. The constant stress of striving to be perfect can also leave people fatigued, stressed and suffering from headaches and insomnia.

Author Amber Rae was in her early 20s and running herself thin working at a Silicon Valley company. She was even taking the stimulant Adderall to help her meet her ridiculously high career expectations. “I was burning the candle at both ends,” she described. “I wasn’t sleeping.” One day after she came home from work, she fainted, eventually waking up with no idea how long she’d been out. When Rae went to a doctor, she was told the episode was caused by depletion in her body. “It was a wakeup call,” she said.

Up until then, she hadn’t been conscious of the story she’d been telling herself — that her lovability and safety as a human were tied to being perfect. “I’d been telling myself this story for my entire life, and it was sucking the joy out of my creative process,” Rae, now 34, said. “Something had to change.”

Perfectionism comes in three common flavors — “self-oriented,” where someone demands perfection from themselves; “other-oriented,” where they demand perfection from others around them (like spouses, co-workers or friends), and “socially prescribed” perfectionism, where the person feels external pressure from the larger world and society to be perfect.

The latter type seems to be especially pernicious, says Gordon Flett, a psychologist at York University in Canada, because it’s consistently linked to health and emotional problems. He recently published a paper looking at people with chronic health problems like fibromyalgia or heart problems. About one in four of them scored high in socially prescribed perfectionism, where they felt that society or people around them expected them to be perfect.

Striving for perfection isn’t the same as being competitive or aiming for excellence, which can be healthy things. What makes perfectionism toxic is that you’re holding yourself to an impossible standard that can never be achieved — essentially setting yourself up for perpetual failure.

As a budding artist, Rae remembers ripping up middle school art projects at the sight of any small imperfection. “I had high taste, and my talent wasn’t there yet, so I would get frustrated. I felt like I had a potential that I wasn’t living up to,” she says. Rae had created a story for herself that perfection meant she would be loved. “If I could do things perfectly and look perfect, then people would love and approve of me and I’d be safe,” Rae says.

“It’s really difficult when people feel like they’re being held up to impossible standards. And when these people are successful, they may fear that now the expectations are just raised even further,” Flett says. “You see an escalating sense of pressure.”

Eating disorders are a common manifestation of perfectionism, according to Karina Limburg, a clinical psychologist at Ludwig-Maximilians University in Munich, Germany, who authored a study linking perfectionism to mental health disorders. She recalls one woman she saw with anorexia nervosa who had extremely strict and rigid rules about eating.

“Every time she ate a forbidden food, it meant she had failed to meet her standards,” Limburg said. A healthy person might say, “Oh well, I didn’t make that goal,” but for this patient a single lapse could completely wreck her feelings of self-worth. “She based her self-worth on reaching a perfect goal weight,” Limburg said, and this impossible standard set her up for failure.

There does seem to be at least some genetic component to perfectionism, but to what extent it’s an innate, heritable disposition versus something that’s learned or provoked by one’s environment isn’t completely clear, Flett explained. “If you are a perfectionist, you’re more likely to have perfectionist parents. It can be genetic, and it can also be modeling and circumstances.”

When Magee was growing up, success felt like a way to connect with her father on an emotional level. The only times he seemed to really pay attention to her, she said, was when she succeeded at something, like scoring a soccer goal or getting a good grade. “I learned from a young age that I was most likely to be seen and valued when I was achieving something,” she said.

The kind of success-focused parenting Magee experienced could be getting more common. Kids crave love that’s not contingent on math scores or performance in a soccer game, said Simon Sherry, a clinical psychologist and professor at Dalhousie University, yet many parents today feel a sense of competitiveness that they may push onto their kids, whether by pressuring them to get perfect grades so they can get into elite schools or signing them up for extracurricular activities that might look good on a college application. But if a child is only rewarded for high achievement, over time they learn that their value as a person depends on being perfect. “Parents need to be loving their kids without strings attached,” Sherry said.

Instagram, Facebook and other social media platforms also fuel unhealthy comparisons. “It’s a real problem — those social media images end up serving as yard sticks that people can compare themselves to, and a perfectionist is always trying to keep up with the Joneses,” Sherry said. And it’s never been harder to keep up with the Joneses, because today we are constantly bombarded with seemingly perfect images of other peoples’ lives.

Perfectionism doesn’t automatically resolve itself as someone gets older, and in fact may become worse as people age, said Martin Smith, a researcher at York St. John University in the UK. His team published a meta-analysis of the relationship between perfectionism and other personality factors, and found that as people who score high in perfectionism age, they seem to become more prone to experiencing negative emotions like anger, anxiety, and irritability and they also become less conscientious.

Smith said that what may be happening is that over time, as perfectionists repeatedly fall short of their impossible standards, they start to adopt a bleak view of their past. They tend to see most of their experiences as failures, since they only rarely achieve the perfection they’re striving for.

In school or in a competitive sport setting, it’s often fairly easy to gauge performance relative to others via grades or other statistics. But in the workplace, comparisons to colleagues may be more subjective, and for a perfectionist who is always striving to be the best, this can be difficult, Smith says. “It’s rare that you can say that you got a 95 percent on this thing at work. It’s a lot more murky.”

Several decades of research on perfectionism has shown that perfectionism is associated with suicidal thinking and behaviors. Suicidal thoughts and impulses are more common among perfectionists than most people appreciate, Sherry said. Red flags can include taking extra measures to hide distress, and actively presenting a picture of perfection that doesn’t reflect reality. These are facades, Sherry explained, that can often be seen through by the people close to the person.

Rae realized she’d built an identity around her need to be perfect, and it was one she had to let go of if she were to get past her destructive behavior. To help her recognize when she was falling into her old patterns, Rae gave her inner perfectionist a name — Grace. Giving it a name helped her find some distance that allowed her to recognize what was happening when she fell into that way of thinking. “I could say, oh that’s Grace. And instead of bashing Grace, I could have compassion for her.” She would ask herself, what does Grace need right now? The answer could help her understand the needs that her perfectionism was bubbling up to try and meet.

Treating perfectionism, Hewitt said, is somewhat like working with a child who is afraid of an imaginary monster under their bed. He remembers a patient who self-identified as a perfectionist who casually mentioned in their first meeting that when she was five years old, her parents had sent her away to live with relatives while they arranged the family’s overseas move. She remembered being reunited with her mother after the absence and being transfixed by how beautiful she looked. After that, she made it her life’s work to be the perfect daughter, with the subconscious hope that if only she were perfect she’d never be separated from her mother again. Cases like these, Hewitt explained, are often more about the underlying relationship than anything else.

Ironically, many people pursue perfectionism with the belief that striving for perfection will make them more acceptable to other people, but instead what more often happens is that they’re perceived as prickly, guarded or hostile, Hewitt says. “It’s meant to garner acceptance and closeness to others, but instead, it pushes people away — that’s the neurotic paradox.”

Magee’s perfectionism made it difficult for her to build friendships. She was always seeking recognition and affirmation, rather than the vulnerable human connections that friendships require. “I would have relationships, but they were performative, not authentic,” she said.

Eventually Magee, now 26 and living in Seattle and working as a co-dependency recovery coach, learned that she had to let go a little and allow herself to show up with all her imperfections. “I had to learn to be able to say, ‘I feel anxious today, but I’m still going to hang out with you.’” It took some practice, but she eventually learned to trust that she could show up and not be perfect and still feel valued. It’s taken time, but she now has two or three close friends she can totally feel like herself around. These friendships have helped her see that “I can be imperfect and everything can be fine!”

Christie Aschwanden is an award-winning science journalist. She’s the author of the New York Times bestseller, Good to Go: What the Athlete in All of Us Can Learn from the Strange Science of Recovery, and co-host of the podcast Emerging Form. Find her on Twitter at @CragCrest.

Author: Christie Aschwanden

Read More