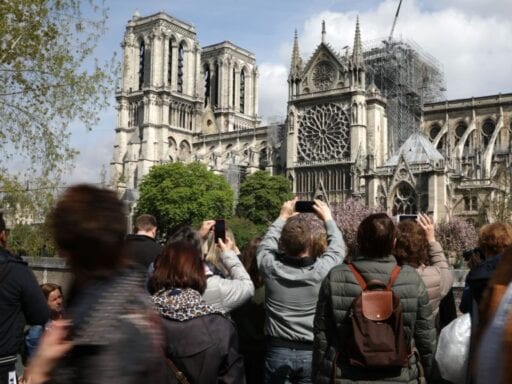

Some say the $1 billion donated to the Paris cathedral should’ve been directed elsewhere.

As more than $1 billion has rolled in to repair the Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris, a debate is raging over whether the glut of donations would have been better spent on other causes.

People on social media asked why similar support was not going to Native American sacred lands destroyed in fracking and development, to historically black Louisiana churches devastated in arson attacks, to the fight against climate change, or to development aid for African countries. (In the case of black churches, the post-Notre Dame publicity led to a surge in donations.)

Meanwhile, within France, many are saying the heaps of money should be directed toward French people in poverty. Over the past year, homelessness has increased by 21 percent in Paris. And for months, the “Yellow Vest” movement has been protesting rising social inequality in the country. The Yellow Vests and their allies saw President Emmanuel Macron’s pledge to rebuild Notre Dame within five years as further proof that he’s prioritizing the wrong causes.

“If they can give tens of millions to rebuild Notre Dame, then they should stop telling us there is no money to help with the social emergency,” Philippe Martinez, who leads the General Confederation of Labor trade union, said on Wednesday.

What should we make of the competing priorities people are pushing in this debate? As potential donors, how do we assess where our money would be best allocated? And should we be criticizing other people when they donate to causes we think are less important?

You don’t have to choose between helping the poor and helping Notre Dame

It might be tempting to think you have to align yourself with only one camp in this debate, especially when the camps themselves present the situation that way. But that’s not the case.

Say you side with the Yellow Vests and argue that poverty is the problem much more deserving of — and likely to benefit from — your resources. You’d be in good company: Movements like effective altruism (EA) have argued that people should try harder to identify high-impact charities, and direct more of their money toward them. Effective altruists tend to think the best charities will focus on an issue that meets three criteria: It’s important (it affects many lives in a massive way), it’s tractable (extra resources will do a lot to fix it), and it’s neglected (not that many people are devoted to this issue yet).

But they’re not so extreme as to say you should only ever donate to the charity where your money will do the most good.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/16178122/notre_dame_interior_GettyImages_1137551205.jpg) AFP / Getty Images

AFP / Getty ImagesJulia Wise, who works in the EA community, recently wrote a blog post explaining that although cost-effectiveness analysis is a useful tool that she wishes more people applied to more problems, it’s not meant to govern every single decision you make. That’s because you have lots of different goals, from improving the world to feeling connected in your friendships. Wise explains:

If I donate to my friend’s fundraiser for her sick uncle, I’m pursuing a goal. But it’s the goal of “support my friend and our friendship,” not my goal of “make the world as good as possible.” When I make a decision, it’s better if I’m clear about which goal I’m pursuing. I don’t have to beat myself up about this money not being used for optimizing the world — that was never the point of that donation. That money is coming from my “personal satisfaction” budget, along with getting coffee with my friend.

I have another pot of money set aside for donating as effectively as I can. When I’m deciding what to do with that money, I turn on that bright light of cost-effectiveness and try to make as much progress as I can on the world’s problems. … The best cause I can find usually ends up being one that I didn’t previously have any personal connection to, and that doesn’t nicely connect with my personal life. And that’s fine, because personal meaning-making is not my goal here.

Wise recommends that we be clear with ourselves about which goal we’re pursuing whenever we devote time and money to a given cause. That way we’ll notice if, over time, we’re devoting ourselves only to dramatic causes (like a tragic fire) and causes that have a personal connection, or whether we’re also making progress on other world issues that we believe are important.

This seems like a useful way of keeping us accountable to ourselves. And you can hear an echo of it in a French homelessness charity’s response to the outpouring of support for Notre Dame.

The Abbe Pierre Foundation, which is named after a prominent priest whose funeral was held at Notre Dame in 2007, said: “We are very attached to where Father Pierre’s funeral was held. But we are equally committed to his cause. If you could contribute even one percent of the amount to the homeless, we would be moved.”

In other words, there’s nothing wrong with donating to the restoration of a burned cathedral if that’s something we’re passionate about. We can take that out of our “personal satisfaction” budget, or maybe our “preserving cultural identity” budget. But it’s worth making sure we’re also remembering the other problems — including urgent ones like homelessness — and dedicating resources to those problems in proportion to their urgency.

Sign up for the Future Perfect newsletter. Twice a week, you’ll get a roundup of ideas and solutions for tackling our biggest challenges: improving public health, decreasing human and animal suffering, easing catastrophic risks, and — to put it simply — getting better at doing good.

Author: Sigal Samuel

Read More