If schools in America do reopen, other countries have some best practices worth adopting.

Cities and states across the United States are grappling with how — or even whether — to reopen schools this fall amid the ongoing coronavirus pandemic. But the experiences of other countries around the world suggest an uncomfortable reality: While there are some best practices that can help reduce the risk of spreading the virus, there’s still no surefire way to bring children back into classrooms safely.

Countries from Germany to New Zealand to Vietnam have employed all sorts of methods to keep the coronavirus from spreading among students and staff, including having some kids show up in the morning and others in the afternoon; putting a group of students together in a well-ventilated room with a single teacher all day; wearing masks; and administering repeated temperature checks and coronavirus tests.

The results have been varied. In Denmark, for example, coronavirus cases dwindled even as elementary schools and day care centers reopened in April. But Israel saw confirmed cases spike after restarting in-person classroom instruction in May, when the government felt it had a handle on the crisis.

Even if American schools were to take all the necessary precautions learned from other countries, it’s possible some reopenings could still fuel worsening local outbreaks.

There’s another problem, too: The United States is somewhat of an outlier, in terms of both its large population size and its high infection rate. There’s a dearth of coronavirus-related data from schools in countries with populations and/or infection rates similar to America’s, which means that while the experiences of other nations can be illustrative, they’re not entirely instructive.

“There have been lots of different methods taken” around the world to curb the spread inside schools, said Brandon Guthrie, a global health and epidemiology expert at the University of Washington, “but the challenge is that they’re not head-to-head comparisons.”

As a result, “There is no clear consensus about what measures are and are not effective” for a country in America’s situation, Guthrie added.

On top of that, most countries began gradually reopening schools only once they’d gotten their coronavirus outbreaks largely under control. In the US, on the other hand, cases are on the rise, with several states including California, Arizona, Florida, and Texas facing severe outbreaks that are causing state and local officials to rethink the wisdom of reopening. In fact, as of July 8, only four states met the basic criteria that public health experts say are critical to reopen safely.

“No country that has reopened schools so far has had the pandemic under such little control,” said Emiliana Vegas, co-director of the Center for Universal Education at the Brookings Institution. “That’s what’s complicating everything for schools.”

According to the New York Times, as of Wednesday only two of the nation’s 10 largest school districts are in cities that have daily infection rates below 5 percent (among those who are tested). The continuing outbreak in California is why school districts in Los Angeles and San Diego have decided to go completely online in the fall.

Still, President Donald Trump is clear he wants classes to resume in person. Should some local leaders follow his lead, experts say they would do well to adopt strategies from other nations that invested a lot of time and effort into figuring out how best to resume normal operations.

In Germany, Denmark, Norway, Sweden and many other countries, SCHOOLS ARE OPEN WITH NO PROBLEMS. The Dems think it would be bad for them politically if U.S. schools open before the November Election, but is important for the children & families. May cut off funding if not open!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) July 8, 2020

But, experts warn, leaders need to fully understand that opening schools across America incurs a real — and potentially dangerous — risk.

How other countries are reopening schools

A quick look around the world shows how countries are trying to balance the safety of students and staff while regaining a sense of normalcy in the classroom — and with some success.

In New South Wales, a southeastern territory in Australia with Sydney as its capital, students are physically allowed in class only one day a week. It’s up to individual schools to decide which students and teachers attend when — for example, by assigning a certain day to certain grades, or dividing students alphabetically throughout the week.

“We really felt that every student deserves that connection with their teacher, that there wasn’t a single year of schooling that we would want to miss out from that,” Georgina Harrisson, deputy secretary of educational services at the New South Wales Department of Education, told Education Week in June.

Having students present in school only one day a week and continuing education online the rest of the time is still vastly different from the way things were before the pandemic, but it’s at least meant to provide everyone with some sense of normalcy while still keeping people safe.

Meanwhile, in Denmark, the first European country to reopen day care facilities and schools for children between 2 and 12 years old, the main strategy is to keep certain classes in “enclaves.” Essentially, a group of students and one teacher are positioned in a specific part of campus all day with no interaction outside of their assigned pod. They’re even required to eat lunch at their desks, which are positioned a safe distance from others inside their group.

Data from May indicated this reopening strategy didn’t make the country’s already minimal outbreak worse. Despite an initial uptick after schools reopened, infections among children between 1 and 19 years old declined from late April onward. “You cannot see any negative effects from the reopening of schools,” Peter Andersen, an epidemiologist at the Danish Serum Institute, told Reuters at the time.

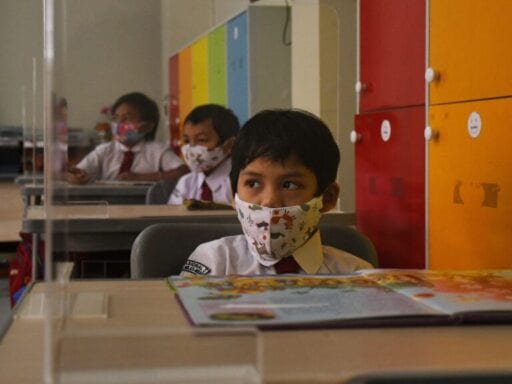

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/20003738/1211674325.jpg.jpg) Manan Vatsyanana/AFP via Getty Images

Manan Vatsyanana/AFP via Getty ImagesOther countries, such as Vietnam, have emphasized ubiquitous mask-wearing.

After a three-month hiatus, some of Vietnam’s 22 million school-aged children and university students were allowed to begin returning to classrooms in May after first passing a daily mandatory temperature check at their school’s entrance. If a child doesn’t have a fever, they’re allowed to attend classes, but they must wear a mask for the entire school day. One school in Hanoi, Vietnam’s capital city, bought 10,000 masks to ensure it had enough for students to use.

Some may have found it cumbersome to wear a mask for hours, but 11-year-old Pham Anh Kiet, who attends a western Hanoi school, didn’t seem to mind. “I feel safe when I wear a mask and have my temperature checked, I am not afraid of being infected with the virus,” he told Agence France-Presse on May 4.

All this would seem to imply that resuming normal school-day operations is relatively low-risk as long as measures like these are put in place. Well, not exactly.

For example, take what’s happening in Israel. On May 17, schools reopened partly because the government felt the disease had been defeated in the country. There was good reason for that at the time: Israel reported only 10 new cases that day. Israel now sees about 1,500 new cases per day — far higher than two months ago. In fact, as of Monday, Israel’s education ministry said around 1,335 students and 691 staff had been infected in schools since the reopen.

There are two important caveats, though. First, Israeli schools weren’t so strict in imposing social distancing and preventive measures inside the classroom, which may have contributed to a wider spread. Second, Israel also lifted bans on large gatherings at the same time, which might indicate some students and staff were infected outside of school.

“Due to the fact that the restrictions were released very fast, it’s difficult to disentangle the effects of each separately,” Eli Waxman, a physicist who heads the panel of experts advising the Israeli government on the coronavirus, told the Wall Street Journal on Tuesday.

Still, Israel’s complications should give US school leaders pause as they consider how, exactly, to bring kids back to school. “It needs to be planned, and it can’t be improvised,” says Brookings’s Vegas.

A natural impulse would be to assume the experiences of the more successful countries would translate to the US context. But such an impulse is, sadly, misguided.

The problem with “lessons learned” from other countries

Dr. Kathryn Edwards, a pediatrician at the Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, walked me through the complexities of designing an experiment to see just how safe it is inside of any school.

Assume you were trying to design a randomized study in which some students wear masks in class and others don’t. Immediately a few alarm bells start ringing: For example, surely some parents of the students who were placed into the non-mask-wearing group would be unhappy their child was going to be unprotected. The school may also have trouble enforcing mask wearing — especially if younger children are the subjects — and may not have the labor or funds to see the study through to the end.

And even if the study overcame all those hurdles, how could anyone be sure the results at one school would be comparable to another? The truth is no one can. “There are a lot of variables present,” Edwards told me, noting each local situation deeply impacts the inner workings of a school. “We’re really struggling with how to study this.”

Which leads to one troubling conclusion: The “lessons learned” from other nations won’t necessarily translate directly to American schools.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/20085489/1227111470.jpg.jpg) Montinique Monroe/Getty Images

Montinique Monroe/Getty Images“There are very few good models that fit the US context,” the University of Washington’s Guthrie said. “From a purely data-driven approach, we have limited information to build off of.”

Only two factors will really determine when it’s safe for parts of the US to reopen schools and how to do so, experts say.

The first is the state of the local coronavirus outbreak itself. “The feasibility is really going to depend on the state of the epidemic in the community,” said Lauren Meyers, a mathematical epidemiologist at the University of Texas at Austin.

Texas’s capital has seen a massive growth in new coronavirus cases over the last few weeks, which makes it an inopportune time to restart in-classroom instruction there. Meyer’s own model indicates a 500-student school in Austin could expect at least four new coronavirus cases if it reopened today. Should the school adopt a zero-tolerance policy — that is, the school would close again once a new coronavirus case was confirmed — then such a reopening would be ultimately ineffective.

In other words, the top factor any school should consider when deciding whether or not to reopen is the state of the coronavirus outside the school’s walls. “If the incidence of coronavirus is high, there will likely be more people infected in schools, who could then transmit the virus further,” Emmi Sarvikivi, an epidemiologist at the National Institute for Health and Welfare in Finland, told me.

The second factor is if US schools have data from areas similar to theirs showing a return to school didn’t further exacerbate the outbreaks in those places. So far, such results aren’t promising.

The University of Washington’s Guthrie pointed me to Quebec, the hardest-hit province in Canada, which decided to reopen schools in May. There were immediate problems: in just the first three weeks, nearly 50 students and over 30 staffers tested positive for the disease.

Quebec, with its high rate of infection and shared border with four US states, is perhaps the best glimpse into what reopening schools in America might look like, experts say. However, they also note that not much can be gleaned from just one region, which is why analysts would like to see more data come in from school systems in similar circumstances.

Despite all this, experts are clear that returning to in-person instruction is paramount. Not only is it the most effective way for all students to learn, but school allows small kids especially to develop social skills they can’t learn at home. It’s why some countries are fine reopening schools as coronavirus cases dwindle as long as precautions are put in place, and are especially comfortable sending younger children back to the classroom since there’s evidence they transmit the disease at lesser rates than adults.

But experts also are clear that returning to classroom instruction will only be safe if and when the US gets a handle on its coronavirus outbreak. “Is it better off returning to physical school? Yes,” said Harvard University education expert Robert Schwartz, “but this administration has made that extremely problematic.”

Support Vox’s explanatory journalism

Every day at Vox, we aim to answer your most important questions and provide you, and our audience around the world, with information that has the power to save lives. Our mission has never been more vital than it is in this moment: to empower you through understanding. Vox’s work is reaching more people than ever, but our distinctive brand of explanatory journalism takes resources — particularly during a pandemic and an economic downturn. Your financial contribution will not constitute a donation, but it will enable our staff to continue to offer free articles, videos, and podcasts at the quality and volume that this moment requires. Please consider making a contribution to Vox today.

Author: Alex Ward

Read More