No Republican “epiphany” will be forthcoming.

All successful politicians traffic in feel-good fantasy. After all, who doesn’t want to hear that hard problems have easy solutions and that whatever feels troubling today is but a passing storm cloud.

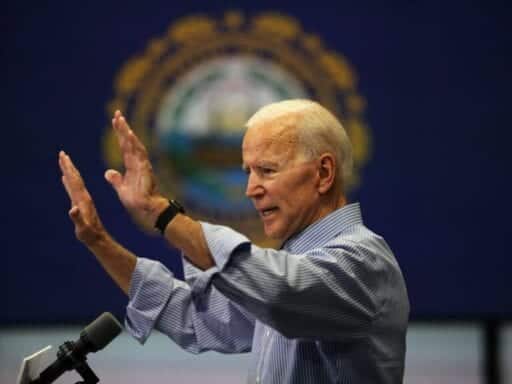

Perhaps it is in this spirit, then, that we should interpret candidate Joe Biden’s campaign trail remark that once President Joe Biden kicks Donald Trump out of the White House, Republicans will have an “epiphany” and start working with Democrats toward consensus.

“I just think there is a way, and the thing that will fundamentally change things is with Donald Trump out of the White House. Not a joke. You will see an epiphany occur among many of my Republican friends,” Biden said. (Though the “not a joke” qualification does raise the obvious question of whether it is, in fact, a joke.)

Certainly, such an epiphany would be a welcome development if it were to occur. And perhaps many voters believe it should be this easy, which is why Biden is peddling this line. Perhaps Biden even believes it himself. But, spoiler alert: It’s not that easy.

Why there will be no “epiphany”

In June 2012, Barack Obama made a similar prediction about Republicans embracing bipartisanship after Obama was re-elected:

”I believe that If we’re successful in this election, when we’re successful in this election, that the fever may break, because there’s a tradition in the Republican Party of more common sense than that. My hope, my expectation, is that after the election, now that it turns out that the goal of beating Obama doesn’t make much sense because I’m not running again, that we can start getting some cooperation again.”

Obviously, Obama’s prediction did not come true. Republicans did not suddenly embrace bipartisanship on November 7, 2012.

Biden’s prediction and Obama’s prediction have the some underlying logic: that Republicans’ hostility to Democrats is personality-based. In Obama’s explanation, it was a fundamental hostility to him personally. In Biden’s case, Republicans are deeply under the spell of Donald Trump, who is uniquely hostile to civility and consensus.

The problem with Obama’s theory was that, once Obama was out of office, Republicans’ hostility transferred seamlessly to another Democrat, Hillary Clinton. The problem with Biden’s theory is that Republicans’ hostility to Democrats did not begin with Donald Trump (see, the Obama administration).

Today, as in 2012, the partisan hostility is highly transferable. It is based neither in opposition to one president nor loyalty to another. It is based in the underlying zero-sum electoral logic that defines the American two-party system and the winner-take-all elections that make the two-party system possible.

As political scientist Frances Lee has eloquently written in her book, Insecure Majorities:

“The primary way that parties make an electoral case for themselves vis-a-vis their opposition is by magnifying their differences. In a two-party system, one party’s loss is another party’s gain. A party looks for ways to make its opposition appear weak and incompetent, and to seem extreme and out of touch with mainstream public opinion. As parties angle for competitive advantage using such tactics, the upshot is a more confrontational style of partisanship in Congress.”

Lee has argued that today’s close partisan balance, with control of national governing institutions potentially up for grabs with every election, has made bipartisan compromise very difficult. The more the “out” party obstructs and attacks the “in” party, the less legitimate the “in” party will seem in the next election.

In short, if Joe Biden assumes office in 2021, what incentive will congressional Republicans have to work with him? Helping a President Biden achieve his policy goals would help Democrats become more popular. Republicans’ future electoral success would depend on Democrats becoming less popular. It’s the same as when Obama began his second term in 2013. This is why the “fever” didn’t break.

It’s also why congressional Democrats immediately went into resistance mode following the 2016 election. Why would Democrats ever work with Republicans to help Donald Trump achieve anything? It’s the same logic, but with a very different emotional feel.

Of course, if you are a Democrat, you might now be thinking something like this: “Of course Democrats had to oppose Trump. He is anathema to everything Democrats stand for.”

And this takes us to the second reason why Republicans are not going to suddenly work with Democrats. Republicans and Democrats represent very different constituencies, with different values. The two parties today have very little overlap. And because their coalitions are so different, they deeply distrust and fear each other.

The parties are really different today

In his campaign remarks, Biden recalled how, over his career, he worked with “a lot of good people” in both parties. “We can get back to that place,” Biden said optimistically. Again, it’s a nice sentiment. But unless Joe Biden has a secret time machine, it ain’t gonna happen.

Joe Biden was first elected in the United States in 1972, when partisan polarization was at a low. In the 1970s, it was fashionable to argue that political parties were on the verge of extinction; there was so much cross-partisan deal-making that partisan labels had become basically meaningless. Congress operated very differently as a result.

Over the course of Biden’s career, partisan polarization has grown steadily. The liberal Republicans and conservative Democrats who once crossed party lines have gone extinct. When Biden was first elected in 1972, Mississippi had two Democratic Senators (John C. Stennis and James Eastland), and Vermont had two Republican Senators (George Aiken and Robert Stafford). Split-ticket voting was at an all-time high.

In short, there were bipartisan deals to be made because genuine cross-party overlap existed on many issues, and many lawmakers were responding to genuine cross-party constituencies.

Those incentives simply don’t exist today. The two parties today are actually two separate parties, with little overlap, in large part due to the nationalization of politics. The two parties today represent genuinely different constituencies and coalitions. The old liberal Republicans from the Northeast who Biden once had lots in common with are now gone. The new conservative Republicans from the South (who replaced the conservative Democrats) have little interest in consensus politics.

Moreover, in the 1970s and into the 1980s, Democrats appeared to have a lock on the House of Representatives, while Republicans appeared to mostly have an advantage in presidential elections. Nobody expected the balance of power to change all that much from election to election, and so there was not much sense holding out for partisan control to shift. Besides, both chambers were mostly decentralized committee-based institutions, where partisan leadership exerted minimal agenda control, so partisan control of the chamber didn’t matter as much.

This is very different today. Today, leadership in Congress is highly centralized, and control of the chamber means total agenda control. It’s a grand prize that demands high-stakes electoral fighting.

What Biden could have said instead

Rather than peddling a fantasy theory in which electing a Democrat to the White House causes a sudden epiphany of bipartisanship, Joe Biden could have said that the political incentives in our system are all screwed up, and that until they change, our politics is going to get even nastier. He could have said that if we want more functional politics, we’re going to need to change the winner-take-all electoral system that has created today’s zero-sum toxic politics.

But that would require some hard explaining. And sunny nostalgia is a much easier, on-brand sell.

But if Biden should have an epiphany of his own and become interested in tackling the hard problems of our broken political system, his staff should let me know — I can get him an advance copy of my forthcoming book. It explains how to change the political incentives so that compromise doesn’t rely on epiphanies that are unlikely to be forthcoming.

Author: Lee Drutman

Read More