Are a strike and a walkout the same thing?

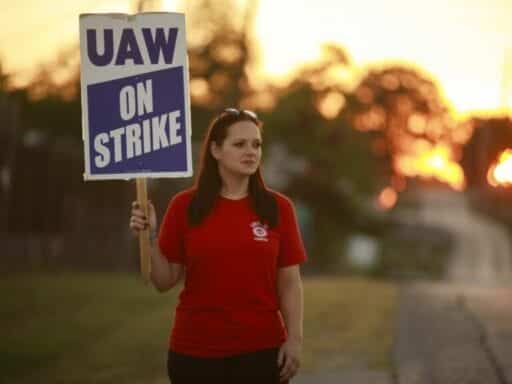

Nearly 1,000 Amazon employees are walking out of work. More than 45,000 GM auto workers are on strike for the fifth day in a row. In October, about 80,000 Kaiser Permanente employees are set to go on strike.

The wave of labor unrest has become a defining feature of the economy since the 2008 Great Recession. In 2018, a record number of employees went on strike: School teachers, hotel workers, health care workers — even Google employees. Most of them were angry about stagnant wages and proposed benefits cuts, but some were just frustrated with company policies.

But all the walkouts have raised the question of what, exactly, counts as a strike and what are the consequences? Is it the same as a walkout? Is it even legal?

I spoke to four labor lawyers across the country to get a better understanding of what legal rights workers have to throw up their hands and walk off the job — and what right a company has to respond.

One law professor pointed out that a walkout to protest climate change, for example, is not protected under federal labor law because it’s not related to an employee’s working conditions. But if workers walk out because they believe their employer (like, say, Amazon) isn’t doing enough to make the company sustainable, then that would likely be a protected work stoppage.

“If everyone walks out or calls in sick, it’s still a strike,” Kenneth Dau-Schmidt, an employment law professor at Indiana University Bloomington, said to me. Whether or not the law protects workers from getting fired depends on the context.

1) Am I allowed to strike?

If you work in the private sector, definitely. It doesn’t matter if you are part of a labor union or not. For government workers, though, it depends.

The National Labor Relations Act of 1935 enshrined the right to strike into law. At the time, workers were reeling from the Great Depression and President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s pro-labor administration saw collective bargaining as a fundamental right. But the law only covered workers in the private sector, as they were more at risk of being exploited.

The NLRA reversed years of federal opposition to organized labor and guaranteed the right of employees to organize, form unions, and bargain collectively with their employers. Striking was considered the most powerful tool in collective bargaining, so it was given special emphasis in the NLRA.

“The law protects the right to strike, no question,” Ruben Garcia, co-director of the Workplace Law Program at the University of Nevada Las Vegas, said to me, regarding employees in the private sector. “You don’t have to give any notice or any reason for walking.”

But this doesn’t apply to all workers. The NLRA doesn’t cover certain transportation workers, agricultural laborers, or public employees. Government employees — state, local, and federal — do not have a right to strike under the federal law.

That said, eight states allow most government employees to strike. Illinois and California, for example, allow teachers to strike. Yet it’s illegal for police and firefighters to walk off the job in any state.

2) What’s the difference between a walkout, a strike, and a work stoppage?

There’s really no difference, legally speaking. All could fall under the “protected concerted activity” clause in the National Labor Relations Act. (Translation: All of them could involve employees organizing to improve their working conditions.) It doesn’t matter if an employee belongs to a union or not.

There are two main types of legal strikes: One is called an economic strike, when workers are bargaining for better pay and benefits. That’s what GM workers are currently doing.

The other one is called an unfair labor practices strike, in which employees stop working because their employer violated labor laws. For example, employees may refuse to return to work because the company fired two union leaders for encouraging workers to join the union. A company can’t retaliate like that — it’s against the law. Workers can file a complaint with the National Labor Relations Board, which enforces the NRLA, and they would likely force the company to rehire the fired workers.

Which brings me to the next question.

3) Can workers get fired for going on strike?

No, but a company can permanently replace a striking worker by hiring someone else. I know it sounds like the same thing, and in practice it is, but there’s some nuance.

The Supreme Court has ruled that companies have a right to hire replacements to keep the business running during the strike. And even when the strike is over, replacement employees have a right to keep their job. All that an employer has to do is guarantee that a striking worker will get first dibs on any job that opens up in the following year. But there’s no guarantee that a position will open up.

So getting fired and getting replaced are basically the same thing.

“It’s a legal distinction with very little practical significance,” James Brudney, the Joseph Crowley chair in labor and employment law at Fordham University, explained to me.

However, employers have been hesitant to hire replacement workers during the wave of labor strikes in recent years.

There are two main reasons: For one, unions generally negotiate the terms to end a strike, and the conditions always include the promise to let workers who walked out return to their jobs.

Another reason is that workers are often hard to replace. Take the example of the GM strike: Not just anyone knows how to assemble a Chevy pickup truck.

“You can’t have people walk off the street and make a car,” Dau-Schmidt said me. “That’s a skilled job.”

But companies can punish workers in other ways. They don’t have to pay striking workers, and they can cut their benefits. In a drastic move, GM decided to cut off striking employees from their health insurance. But that just made workers angrier.

@GM took my sons health insurance from him so he joined Dad on the line this evening. #UAW #UAWStrike #UAWStrong #GMShame

Thankful to the @UAW for providing coverage in light of GMs callous decision. #Medicare4All pic.twitter.com/HQIJ51KCPp— Jyoung (@resistingjen) September 18, 2019

The potential for a backlash is why Amazon probably won’t punish workers who walk out to protest the company’s lack of action on climate change.

“You can do almost anything if you have the bargaining power,” Dau-Schmidt added. “It all depends on how valuable you are.”

Note the “almost.”

5) Is there such a thing as an illegal strike?

Absolutely, though a more accurate term is “unprotected.” Even though private-sector workers have a right to strike, there are rules. There are exceptions to everything.

A sit-in strike is not protected under federal law. That’s when striking employees occupy their workplace and don’t let anyone else get work done, which was common in the 1930s.

A slow-down strike, in which employees intentionally slow down their work pace, is also unprotected, says Kate Andrias, a law professor at the University of Michigan. So is an “intermittent strike,” when employees say they will strike on-and-off over a period of time.

An employer could easily fire workers for taking part in unlawful strikes.

For union members, there are usually strict limits on walkouts. Most collective bargaining agreements include a guarantee that workers will not strike for the duration of a contract. That’s why GM workers went on strike the minute their contract expired at midnight. When employees go on strike without union approval, that’s called a “wildcat” strike. And if it violates the contract, a union can discipline those members or else the company may sue.

Some of the most famous illegal strikes in recent years have been the teachers strikes. Because government employees are not covered by the NLRA, they are subject to state laws. And in West Virginia, Kentucky, and Oklahoma, it’s illegal for public school teachers to strike.

Teachers in these states went on strike anyway, and most of them got the pay raises they wanted. They could have all gotten fired, or even put in jail. But they had an advantage: strength in numbers.

“You can’t replace all these teachers en masse, especially with the low wages that they were paying,” Dau-Schmidt said. “If you’re hard to replace and you’re unified, you can get away with it.”

Author: Alexia Fernández Campbell

Read More