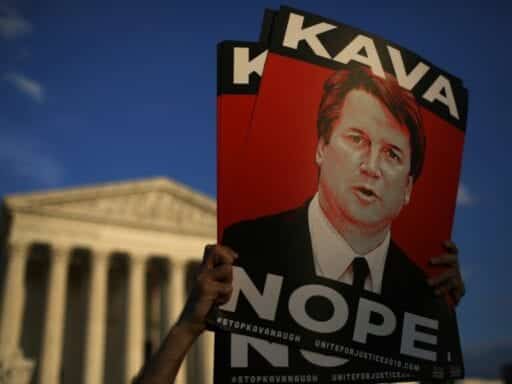

America will be forever changed after Kavanaugh’s divisive entry to the Court.

The battle over Brett Kavanaugh’s confirmation to the Supreme Court is over, and Republicans have won.

The 53-year-old DC Circuit Court judge will be promoted to the nation’s highest court, where he could well sit for decades. Christine Blasey Ford’s decision to come forward with sexual assault allegations against him, as inspiring as it may have been to many across the country, did not, in the end, prevent Kavanaugh’s confirmation.

The consequences from all this will be enormous. Key Supreme Court precedents on abortion rights, economic regulation, and many other issues hang in the balance — as does the Court’s very legitimacy after this intensely controversial process. There will be major political and cultural ramifications as well, as the midterm elections play out and the country grapples with what this means for #MeToo.

Here, then, are several takeaways from how Kavanaugh’s confirmation played out, and a look at what might be next.

Christine Blasey Ford unintentionally gave us a test of the #MeToo movement. Conservatives largely failed.

On October 5, 2017 — exactly a year before the Senate invoked cloture on the confirmation of Brett Kavanaugh — New York Times reporters Jodi Kantor and Megan Twohey published an exposé detailing accusations of sexual abuse and misconduct against Harvey Weinstein.

In the year since, women have spoken out. Not just by bringing accusations against other powerful men, but also in conversation with men (or more often with each other), in Facebook posts and group texts and living rooms — about things they had carried inside them in silence and shame. They were speaking out not as a means of group therapy — to the contrary, the past year has been emotionally exhausting — but as a political declaration.

That conversation — the #MeToo movement — has brought certain tenets into public understanding. That male misbehavior was accepted for a very long time, and that things that seem flagrantly wrong were often not treated as such when they happened. That long-ago traumas still ripple through victims’ lives. That how someone treats vulnerable women is a reflection of his character; that someone who seems like a “good man,” and generally does the right thing, doesn’t get a pass; that the reflex to close ranks against an accused peer is part of what shames victims into silence. That people should face social and professional consequences for socially and professionally unacceptable behavior, even if it doesn’t rise to the level of a crime.

That America might finally be ready to believe women.

If Kavanaugh had been nominated instead of Neil Gorsuch in early 2017, maybe Ford wouldn’t even have sent a letter to her representatives in Congress; she might not have thought her story mattered. She ultimately (if unwittingly) tested the strength of the #MeToo movement with public testimony last week. In some circles, her performance was seen as courageous — a show of strength that few would be able to muster and no one should have to. Few Republicans, even, dared to mock or question Ford directly, with the infuriating exception of the president of the United States.

Conservatives might not have openly doubted Ford’s story — a level of respect we might not have witnessed before #MeToo — but in the end, some of the justifications they offered echoed all the same old clichés that women have spent the past year or more debunking: that social sanctions against someone should be applied only if their accusers meet criminal standards of proof; that sexual assault is always an unknowable matter of he said, she said; that what happened 35 years ago doesn’t matter.

Taking #MeToo seriously requires accepting that norms have shifted, and that past behavior might need to be reexamined, or that people might need to apologize for things (like an inside joke in a yearbook) that seemed fine at the time. And the haste to move forward and confirm Brett Kavanaugh has been the latest reminder that people are uncomfortable looking backward; they would rather skip to the end, and to forgiveness.

—Dara Lind

Mitch McConnell proves (again) that he delivers for donors

In July of last year, Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell was overheard on the streets of Washington saying, “I’d really like to get that Kennedy slot.”

Now he’s got it.

By successfully ramming through Brett Kavanaugh’s nomination despite his unpopularity and despite Christine Blasey Ford’s sexual assault allegations, McConnell has delivered an enormously consequential prize to his political backers: He’s locked in conservative control of the Supreme Court, perhaps for a generation.

This is what the religious right, GOP megadonors, business groups, and the Federalist Society network of conservative legal activists care so intensely about, and why they’ve worked so hard to put McConnell and his party in power and keep them there.

McConnell understood full well how important this was to them, and has been willing to embrace controversial and unconventional political tactics to deliver it: refusing to consider any Obama replacement for Antonin Scalia, changing Senate rules to confirm Neil Gorsuch, and vowing to “plow right through” (his words) Kavanaugh’s nomination even though Ford had come forward.

It was remarkably ugly, but McConnell got what he wanted. His aggressive, uncompromising strategy, for both Scalia’s and Kennedy’s replacements, succeeded.

—Andrew Prokop

Lisa Murkowski listened to the victims of sexual assault — and the coalition that wrote her into office

In the end, only one Republican senator stood up to McConnell and cast a dissenting vote in Kavanaugh’s confirmation: Alaska’s Sen. Lisa Murkowski. (She ultimately voted “present” on the final vote so her colleague Sen. Steve Daines (R-MT) could attend his daughter’s wedding.)

“I believe Brett Kavanaugh’s a good man,” Murkowski said. “It just may be that in my view he’s not the right man for the court at this time.”

For weeks, Democrats and Republicans have been talking past each other on Kavanaugh’s nomination. As Democrats called for a thorough investigation into the allegations of sexual misconduct, Republican leaders called it nothing more than a partisan scheme to obstruct the confirmation process. But the entire time, Murkowski seemed to be looking past the partisan bickering. She emphasized the importance of listening to the accusers.

“We are now in a place where it’s not about whether or not Judge Kavanaugh is qualified,” she told the New York Times. “It is about whether or not a woman who has been a victim at some point in her life is to be believed.”

And when her own party’s leaders brushed away calls for an independent FBI investigation into the allegations, she expressed a need for more facts — that an FBI investigation could bring.

But even before the allegations of sexual misconduct were brought forward, Murkowski’s vote was uncertain. She is one of the few in the Republican Senate conference who supports abortion rights — an issue that was raised heavily during Kavanaugh’s initial hearings. She was also under pressure from Alaska’s Native population to reject Kavanaugh’s nomination, out of concern for his positions on health care and American Indian tribes’ rights. She met with sexual assault survivors and Native American leaders from her state throughout the confirmation process.

Those voices likely shaped her vote, because they are the same voices that put her in office. It goes back to 2010: After losing her Republican primary to a Tea Party insurgent, Murkowski managed to band together a unique political coalition of Alaska Natives, Democrats, and centrist Republicans to win as a write-in candidate.

Ever since, she’s made it clear that she’s not going to vote with Republicans because they tell her to. Last year, she was one of Republican leaders’ major obstacles in repealing Obamacare, and now, even in a close Supreme Court vote, she stuck to her guns.

—Tara Golshan

The conservative movement finally got its majority on the Supreme Court

Conservatives have been on a mission to remake federal courts for decades.

After witnessing the heyday of liberalism on the Supreme Court in the 1960s and ’70s — a time when the Court ordered schools integrated, legalized abortion, and outlawed discriminatory voting laws in Southern states — conservatives saw the judiciary as a tyranny run by liberal justices and law schools. Those decisions were seismic cultural shifts, and conservatives were tired of feeling powerless to stop, slow, or reverse these changes.

So they set out to grow the ranks of conservatives in law schools, in federal courts, and ultimately at the Supreme Court. (The Federalist Society, of which Brett Kavanaugh was once a member and which vetted Trump’s list of all other possible nominees, was founded in the early 1980s.)

Now, with Kavanaugh as the fifth vote in the Court’s conservative bloc, the Federalist Society and their fellow activists are going to get their prize. Kavanaugh is more conservative than Republican-appointed Justice Anthony Kennedy, whom he is replacing, and though Kavanaugh gave a lot of non-answers on controversial topics throughout his confirmation hearings, conservatives widely expect he will hand down victories on restricting abortion, striking down affirmative action, and protecting corporations from onerous environmental regulations.

This explains why all the debate about the allegations of sexual misconduct against him didn’t make much of a difference. Conservatives saw this as one of their few opportunities to dominate the Supreme Court. Frustrated liberals could never gain any traction, no matter how serious the charges, be it sexual assault, possible perjury, or his display of partisanship. Republicans have been putting up with Trump precisely for this moment. For them, the mission has always been about getting a majority of conservatives on the Court.

Indeed, as Vox’s Jane Coaston pointed out, 56 percent of voters who found the Supreme Court nominations to be “the most important factor” went for Trump in 2016. Republicans made a deal: They’d protect Trump, and Trump would give them their Supreme Court nominee. Now they have him.

—Kay Steiger

Susan Collins and most Republican women don’t believe women when it’s their guy getting accused

Republican women have been at an impossible crossroads ever since the election of President Donald Trump.

While many may agree with his policy agenda, they’ve also been forced to sidestep his numerous sexual misconduct allegations along with his crude and demeaning rhetoric toward women — the best example of which came in the now-infamous Access Hollywood tape, which leaked two years ago Sunday: “Grab ’em by the pussy. You can do anything,” he said.

Republican women like Rep. Martha Roby (R-AL), who withdrew her support for him at the time, have seen themselves penalized at the polls for speaking out. Rep. Martha McSally (R-AZ) — who never even endorsed Trump in 2016 — has now been forced to cozy up to him as she vies for a Senate seat.

Republicans — women included — have broadly avoided confronting Trump’s past bad behavior, including the 20-plus sexual misconduct allegations he’s faced, in favor of getting their policies jammed through Congress.

Kavanaugh’s nomination gave Republicans the Diet Coke version of this years-long dilemma with Trump. He is a conservative justice. He will likely help advance rulings on issues like corporate power, abortion rights, and gun control that Republicans will herald. His confirmation is a Republican win. Despite his qualifications, however, Kavanaugh — and his nomination process — have been marred by multiple allegations of sexual misconduct.

And Republicans’ decision to support him anyway has also shined a light on the longstanding partisan divide in how likely people are to believe women.

A New York Times/Siena College poll found a stark split between Republican and Democratic women on this subject, with 64 percent of Democratic women believing Christine Blasey Ford’s account, and just 7 percent of Republican women feeling the same.

Against this backdrop, Republican senators ultimately had two options: They could trust Ford’s testimony — and reject Kavanaugh — as Sen. Lisa Murkowski has done, and in doing so could potentially incur the wrath of their party and face high political costs. Or they could support him and cast doubt on the credibility of the allegations, an approach trumpeted by the male-dominated conference.

With Republican Sens. Shelley Moore Capito (WV), Joni Ernst (IA), and Cindy Hyde-Smith (MS) sitting behind her on the Senate floor, Sen. Susan Collins announced on Friday that she had chosen the latter. “I believe that she is a survivor of a sexual assault and that this trauma has upended her life,” she said. “Nevertheless, the four witnesses she named could not corroborate any of the events of that evening gathering where she says the assault occurred.”

—Li Zhou

The Supreme Court is damaged as an institution — perhaps irrevocably

In confirming Kavanaugh within years of blocking Merrick Garland, Republicans have done extraordinary damage to the Supreme Court itself.

The Court’s legitimacy depends on most Americans viewing it as above the political fray, an institution whose decisions are driven by legal reasoning not by the justices’ partisan leanings.

But Republicans just confirmed Kavanaugh with a razor-thin, almost entirely partisan majority. And they did it after Kavanaugh’s fiery and nakedly partisan testimony before the Senate Judiciary Committee, in which he blamed the sexual assault allegations against him on a left-wing conspiracy. They were, he said, a “calculated and orchestrated political hit, fueled with apparent pent-up anger about President Trump and the 2016 election.”

The September 27 hearing revealed a justice who was less an “impartial arbiter” of the law and more a partisan creature who would take his political grudges to the Supreme Court. He claimed, without evidence, that Democrats were going after him to get “revenge on behalf of the Clintons,” with the support of “millions of dollars in money from outside, left-wing opposition groups.” He was defiant, even downright rude, toward the Democratic senators who asked him questions.

And after all of that, you have Kavanaugh rammed through despite the cloud of sexual assault allegations, after an FBI investigation Democrats (correctly) believe was too limited to help adjudicate the truth of the allegations against the now-justice.

Chief Justice John Roberts has long been concerned with the Court’s legitimacy and standing as a neutral arbiter. This appears to be part of the calculation behind his decision to uphold the Affordable Care Act: Roberts was worried about the Court being perceived as simply a partisan Republican actor.

Kavanaugh’s very presence on the Court, especially after the clearly partisan blockade of Merrick Garland (President Barack Obama’s 2016 nominee to fill the spot on the bench that Neil Gorsuch eventually did), has led to what Roberts has long tried to avoid here. It will be hard for many liberals to accept Court rulings that go against them as legitimate and fair, rather than as the outcome of a partisan Republican majority.

And that is a recipe for crisis: The system depends on everyone having faith in the Supreme Court adjudicating partisan disputes. Confirming Kavanaugh, who is the most unpopular Supreme Court nominee ever to be approved by the Senate, could quite plausibly collapse this consensus.

—Zack Beauchamp

Some red-state Democrats voted no — come what may in November

Sen. Joe Manchin (D-WV) was the one red-state Democrat facing a tough reelection in 2018 who voted for Brett Kavanaugh. But two more red-state senators — Heidi Heitkamp (ND) and Joe Donnelly (IN) voted against him, and it could cost them in their bids for reelection.

Both Donnelly and Heitkamp voted for Trump’s first Supreme Court nominee Neil Gorsuch, but both made clear they were troubled by the sexual assault allegations against Kavanaugh and talked about the need to listen to sexual assault survivors.

Heitkamp, the Democrat from North Dakota, tops many lists of most endangered senators. She’s running against Republican Kevin Cramer, who is leading recent polls by about 8 points, according to the latest RealClearPolitics average. Trump won North Dakota by 35 points, and the majority of the state’s voters support Kavanaugh’s nomination to the Supreme Court; in a recent Fox News poll, 34 percent of likely voters surveyed said they’d be less likely to vote for Heitkamp if she voted against Kavanaugh, and another 46 percent said it wouldn’t have an impact on their vote.

Donnelly announced his opposition to Kavanaugh last week. The Indiana senator appears to be in a better spot polling-wise than Heitkamp — but he’s just 2.5 points ahead of Republican challenger Mike Braun according to the RealClearPolitics spread, so it’s still a very close race.

Ironically, Manchin might be the best off of all of them — he’s leading in some polls by double digits — but he seemed unpersuaded by Ford’s testimony. Still, he is running in a state Trump won by 40 points.

Other red-state Democrats, including Sens. Claire McCaskill, Jon Tester, and Bill Nelson, all announced they would vote against Kavanaugh last week.

—Ella Nilsen

House Republicans in Clinton-friendly districts might be goners

Now that Kavanaugh appears to be getting confirmed, it could bode poorly for House Republicans running for reelection in 2018.

When Kavanaugh’s nomination appeared to be in real trouble last week, it had the effect of revving up the Republican base in a way pollsters haven’t seen all election cycle. An NPR/Marist poll released on Wednesday showed that 80 percent of Republican voters polled said the midterms were “very important,” essentially on par with Democratic voters, who were at 82 percent.

Compare that to July, when Republican voters lagged 10 percentage points behind Democrats when asked how important the midterms were. The sudden jump in enthusiasm signaled that Republicans were fired up about Kavanaugh in a way nothing else had been able to achieve.

“The result of hearings, at least in the short run, is the Republican base was awakened,” said Lee Miringoff, director of the Marist Institute for Public Opinion.

Now that it appears Kavanaugh will be confirmed after all, the effect could indeed be short-term. (It’s important to note it’s still too early for enough polling data to tell us if this was a short-term spike or a larger trend among Republican voters.) But Kavanaugh’s drawn-out, embattled confirmation hearing, ending with him being confirmed, could now have the effect of spurring more Democrats to the polls on November 6.

—EN

Author: Kay Steiger