YouTube gives half its revenue to the people who make its videos. Facebook — despite a $1 billion pledge — doesn’t want to do that.

Facebook has nearly 2.9 billion users, so lots of people use Facebook to reach that giant audience. But Facebook wants even more people posting more stuff on its platforms, so it’s going to pay out $1 billion by the end of 2022 to encourage creators — people who make internet content for fun and profit but generally aren’t running full-fledged media companies — to make stuff for Facebook and Instagram. The impetus here is clear: Facebook wants more engaging stuff on its apps, and it’s also trying to compete with the likes of TikTok, Snapchat, and YouTube.

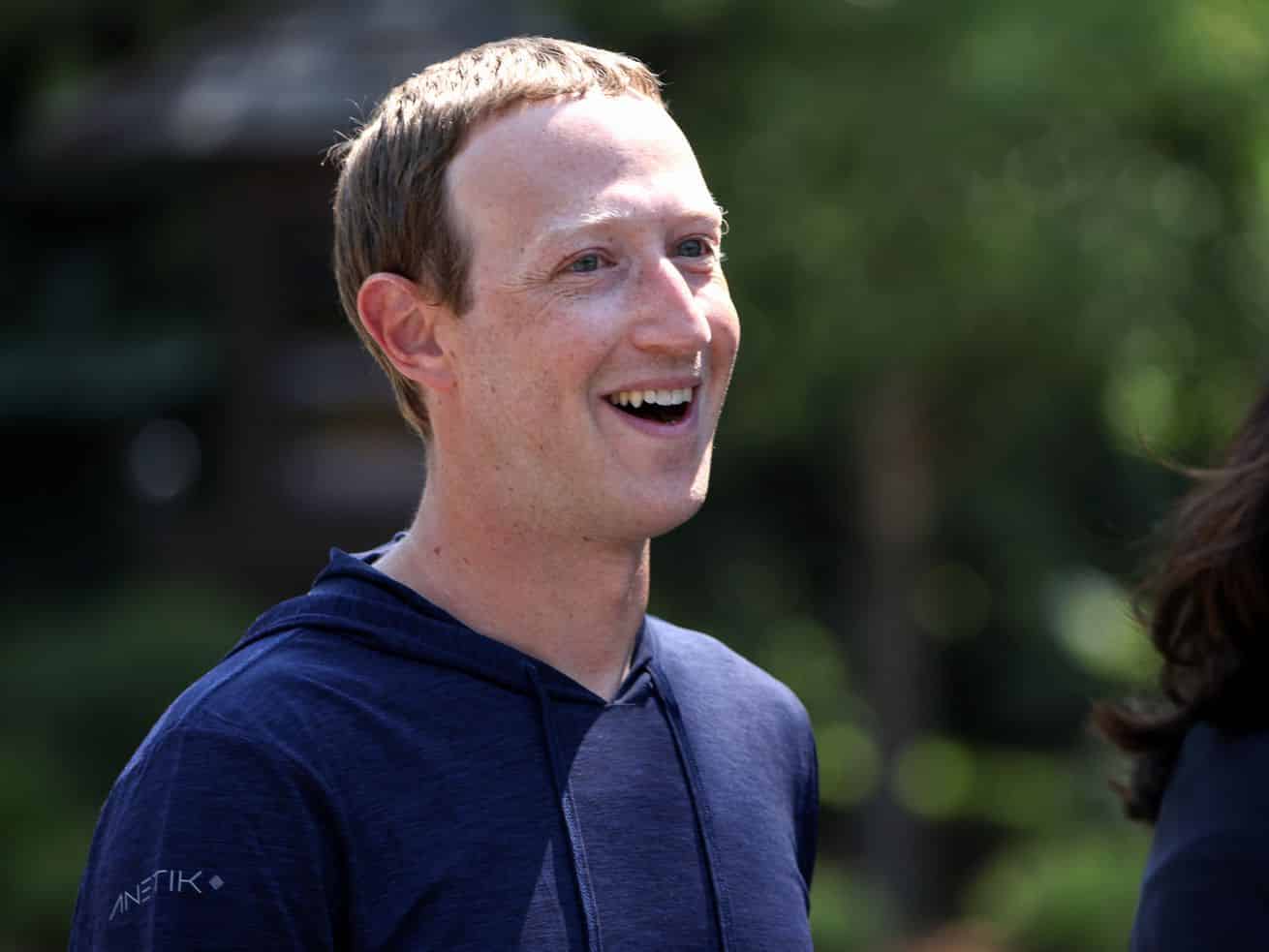

Rewarding people who make stuff for you by paying them is a well-worn playbook for the big internet platforms. Yes, they would really rather have you give them your stuff for free — and you are very much welcome to continue giving Mark Zuckerberg pictures of your dogs and kids. Still, Facebook and its competitors have come to realize that people who are really good at making things often want to get paid for those things. So, fine.

But it’s worth noting that there’s a meaningful difference between Facebook’s newest gambit and the one that Google’s YouTube has been using to great success: Facebook, for now, is giving creators a lot less money.

When you make stuff for YouTube, you get a chance to make money the same way YouTube makes money — from ads that run next to the videos you upload to YouTube. At Facebook, though, there are two different pools of money: One is generated by ads connected to the videos and photos you post on Facebook, and the other is generated by ads everywhere else on Facebook. The first pool is the one that Facebook’s creators can access. The other one is really, really, big. And that’s the one Facebook is keeping all for itself.

This is one of those that’s a little easier to understand with visual aids. So: Here’s a YouTube video by Mr. Beast, the site’s most popular creator. YouTube gets paid for the ads that run before and during the clip, and Jimmy Donaldson, the 23-year-old behind Mr. Beast, gets 55 percent of the revenue those ads generate.

YouTube can also make money other ways, like selling banner ads on its homepage. But the vast majority of its money comes from ads attached directly to the videos it shows to more than 2 billion people every month. So YouTube is directly aligned with the people who generate the stuff that powers YouTube.

At Facebook, though, that connection is much weaker. In theory, Facebook can run ads on videos on things like IG TV, its attempt to create a sorta-YouTube. But most of the money that Facebook makes from ads — and Facebook makes nearly all of its money from ads — isn’t tied directly to content users post there. If you flip through Instagram and see a Nike ad, that ad floats on its own. It’s not tethered to a post from The Rock or Kylie Jenner. The same goes for your Facebook News Feed.

So though Facebook has some ways to share revenue directly with creators, it usually doesn’t give them a cut of money associated with their content. And it’s why lots of the new programs Zuckerberg laid out today are generally connected to frequency or performance — Facebook is fuzzy about what exactly performance means, though — as opposed to the revenue the content generates.

Which means there’s a real money gap for creators who thrive on Facebook versus those on YouTube; it’s why top YouTube creators like Donaldson stick with YouTube instead of trying to branch out onto other platforms. And it’s why YouTube says it paid out $30 billion to its content partners over the last three years.

So if Facebook really wants people to put engaging stuff on Facebook so it can compete with YouTube and TikTok and Twitter and Snapchat, why not give them a chance to make more money?

People familiar with the company tell me there are two reasons. The first is practical: On YouTube, it’s easy to understand that someone who watched a Mr. Beast video watched the ad that ran before it. On Facebook or Instagram, though, it would be difficult to attribute the connection between the Airbnb ad you scrolled past and the Ariana Grande post you eventually landed on.

The second reason is philosophical, and perhaps more important: I’m told that Mark Zuckerberg doesn’t think Facebook content-makers should get a cut of all of Facebook’s revenue. And that while he’s happy Facebook content-makers are giving him content, he thinks he can replace them with others if they don’t like the terms.

That philosophy runs a bit contrary to the fact that Facebook has just said it’s going to spend $1 billion to prompt people to give it content — Facebook clearly feels that it has to compete for creators’ time and energy. On the other hand, $1 billion over a year is much less than $30 billion over three years.

And, to put a fine point on it, the “our content makes Facebook more valuable so Facebook should pay us for it” argument is the one that lawmakers in Australia and an increasing number of European countries are making to justify mandatory payouts from Facebook to publishers — a set of rules Facebook absolutely hates but has had to grudgingly accept.

So telling creators — even those Facebook would really like on the platform — that they can have a piece of the entire Facebook pie — instead of a slice of a slice — doesn’t seem like it’s going to happen.

Author: Peter Kafka

Read More