Savior Complex, The Mission, and the culture behind toxic missionary work.

We aren’t born knowing who the heroes are. We’re taught to see them, instilled with desires to wear their cape, don their uniform, doff their 10-gallon hat, slip into their well-worn shoes.

I don’t know who your heroes were, or how that affected your life’s trajectory, but I know for certain that you had your own heroes. I also know that for me and millions of other millennials in American evangelical churches — like Renee Bach and John Chau, the subjects of two new documentaries — those heroes were Christian missionaries: ordinary people who left their homes, ventured overseas, and preached about Jesus. They were adventurers and explorers, descended from people like the Apostle Paul and Francis of Assisi and David Livingstone and Hudson Taylor, all men who journeyed great distances propelled by their belief that God wanted them to do so because there were people who needed to hear that Jesus could save them from their sins. (Evangelical doesn’t mean evangelism, but the two words come from the same Greek root, evangelion, which means gospel, or good news.)

We read their biographies and heard their stories. People like Amy Carmichael and Jim Elliot were household names. (In my early teens, I wore a sari to play Carmichael in a church skit.) For kids born in the ’80s and ’90s, the age when colorful mass entertainment became a part of evangelical subculture, movies, comic books, and cartoons illustrated their lives. At youth conferences we were exhorted to be “radical” for Jesus, to pledge our lives to go wherever God sent us, to be ready to sacrifice our lives, figuratively or literally, for the gospel. It was going to be amazing. It was heady fuel for the imagination.

Imagination, as it happens, is where a lot of would-be missionaries find their origin story. The subject of The Mission, John Chau, found his inspiration in figures like Elliot, who died in 1956 alongside several white missionaries when they traveled to evangelize the Huaorani of Ecuador. At 26, Chau followed in Elliot’s footsteps, journeying illegally in 2018 to evangelize the Sentinelese people on a remote island off the Indian coast, then making global headlines when his body was found on the shore.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/24951373/themission.jpg)

National Geographic Films

The Mission is an exemplary, thoughtful film about Chau, as well as the larger missionary movement, alongside Western tendencies to exoticize and simultaneously denigrate “primitive” people. (National Geographic Documentary Films is a producer on the movie, and it’s to their credit that the film spends a lot of time on the responsibility that National Geographic, specifically, bears in this area.) Empathetic and non-reactionary, the film weaves together perspectives from people highly skeptical of missions and those who are still true believers. “My friend did something stupid and courageous and bold,” says one of Chau’s closest friends near the start of the film. “I wish I was that bold.”

The Mission — directed by Amanda McBaine and Jesse Moss, whose 2014 The Overnighters was another thoughtful look at a faith community — lets audiences into Chau’s mental framework, as well as those of his critics. They’re grappling with the notion of “foreign missions” — traveling far from home to preach about Jesus. That’s built into the DNA of the modern evangelical movement, which was born in a period that coincided, not entirely accidentally, with the height of European colonialism. But Christianity is an evangelistic religion, and spreading the “good news” has been a fundamental part of the practice in one way or another since the start.

Yet as with most things in the age of mass media, it’s taken on its own turns of phrase and genre conventions. That’s why it’s hard for me to know how some of the film’s other interviewees sound to people who aren’t conversant in the very particular linguistic turns and codes of contemporary evangelical culture. Does “unreached people group” mean something? What about “the gospel call”? For those familiar with the language, though — and, I have to assume, even those who aren’t — The Mission digs directly into how the missions movement of this era often works: by creating what one pastor calls “fantasies” in the minds of young people, building up a celebrity culture around missionaries, then making an emotional plea to them to join the effort.

The actual work of missionaries, an issue that can deserve careful critique of its own, isn’t the focus of The Mission, though of course it comes up. Instead, the documentary deals with the culture that’s sprung up around promoting missionary work. Ways of talking and thinking about “unreached people” that dehumanizes and suggests they’re somehow not “modern,” the way we are. An encouragement of “idealism masquerading as God’s calling,” as one of Chau’s former pastors calls it in the film. There’s a wide range of views about missionary work, as wide a range as the types of work people engage in and the good and harm it can promote. What The Mission is wise to recognize is that even proponents need to reckon with the way missions work has been spoken about and promoted to young people in recent decades.

This issue runs directly parallel to the cottage industry that sprung up around creating “martyrs” from several students murdered at Columbine in 1999, a market that expanded to books, movies, songs, and conferences. On the surface, these were all aimed at creating a “radical” faith — there’s that word again — in young evangelical millennials, who’d be willing to stand up and declare their faith even when faced with opposition. Yet the method created a martyrdom fantasy in teens virtually indistinguishable from the feeling that propelled Chau to go against the wishes of the people he was so certain he was supposed to visit, love, and evangelize. (The Sentinelese are isolated by choice; as one person in the film puts it, “Outsiders coming there with friendship in their hearts can do a lot of harm.”)

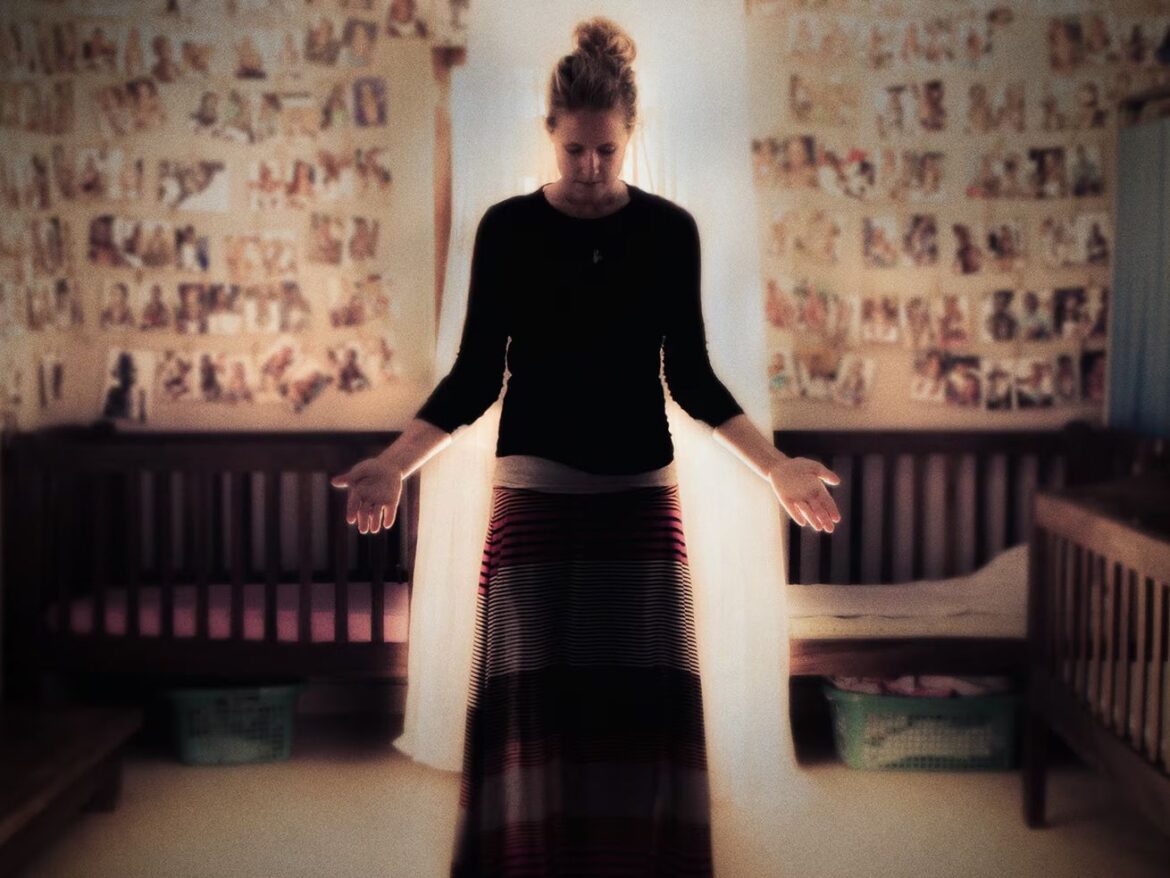

Most importantly, The Mission spotlights how stories, told with breathless admiration, create expectations in youthful, idealistic Christians who long to serve others so that they, too, will be the center of a heroic story. That same idea is at the center of Savior Complex, a three-episode HBO documentary series about Renee Bach, the Virginian who moved to Jinja, Uganda (a center of NGO work) when barely out of her teens. She launched a malnutrition rehabilitation center called Serving His Children that took in children discharged from the local hospital who needed treatment before returning home. In 2019, she came under fire for running the clinic without medical training (or, it turns out, being registered with the government as a medical NGO at all). She’s since returned to Virginia, and she and her mother — who was among the small leadership staff in her organization — are among the main subjects of the documentary.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/24951376/saviorcomplex2.jpg)

HBO

Savior Complex is a tad clunkier in its storytelling than The Mission, though the reasons for one of its more unwieldy elements — the inclusion of an advocacy group called No White Saviors, which poured enormous energy into calling out Bach on social media platforms — becomes vitally clear by the end of the series.

Yet it’s a perfect companion piece, particularly for the incisive diagnosis raised by former Serving His Children volunteer Jackie Kramlich, a young nurse who moved to Jinja with her husband and became frustrated with what she saw as Bach’s inability to take criticism or suggestions, even from people more educated than herself. “I think Renee got into a fantasy that she was ordained and special and set apart,” Kramlich says. Her husband Chris agrees, saying he believes that “Renee felt like if she took advice from other people it would lessen her value to the story of being someone that God worked through to heal these children.”

“Lessen her value to the story” — that’s where it clicked for me. An element of solipsism exists in all of us, even those who want to spend their lives serving others. We all want to believe we’re in the right, that we’re doing the enlightened thing. What the Kramlichs saw in Bach’s unwillingness to take medical advice, however, was the belief that she was the heroine of this story — that she was appointed by God, in the way God appointed others in the past, to save these children, and that she thus innately had the skill to do so. “God doesn’t call the qualified, he qualifies the called,” as the popular saying (and the first episode’s title) goes.

It’s an impulse that does, in fact, run counter to both Christian teaching (in which Jesus is always supposed to be the hero) and to being a good person. As my thesis director put it to me in grad school, when you tell your own story, you should be the protagonist, but probably not the hero.

That is not the way a lot of missionary storytelling works — nor the way that “white savior” stories, or “magical teacher” stories, or any other story that fires up youthful idealism, often work. Savior Complex even gently suggests that the kind of crusading the No White Saviors group and others like it engaged in falls into the same pattern: the idea that passion and drive and righteousness are enough to make change that matters.

The fact of the matter, as any long-time advocate will tell you, is that activism, service, and saving the world is hard, painful, frustrating, and often very boring work. It is not glamorous; it does not feel heroic; it is often ignored entirely. People like to give money to celebrities and people with good stories. They want to be those people. Especially when they’re young and full of possibility.

In this way, The Mission and Savior Complex contain a lesson for everyone, whether they find missions work reprehensible, admirable, or something in between. Heroes that we’ve heard of are just people with well-told stories on well-prepared platforms. The real heroic work happens in the shadows and the dirt. And very, very few of us are ready to take that on.

Savior Complex premieres on HBO on September 26 at 9 pm ET and begins streaming on Max. The Mission opens in theaters on October 13.