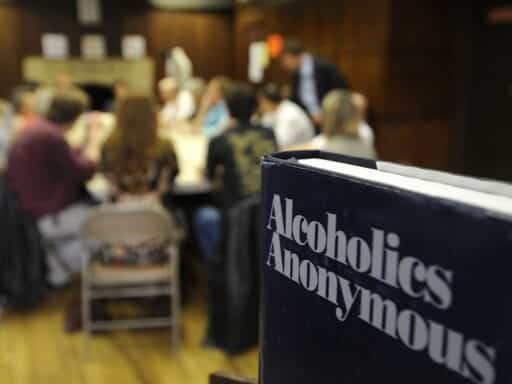

The 12-step approach doesn’t work for everyone, but it can be as effective as other forms of treatment for some people.

Addiction treatment based on Alcoholics Anonymous works as well as or better than scientifically proven treatments for alcohol addiction, according to a new review of previous studies by Cochrane, an organization renowned for its analyses of scientific research.

The review does not mean that AA and treatments that use the 12 steps, which are derived from AA, work for everyone with alcohol addiction. But it shows that, at least for some people, AA and 12-step treatments work as well as alternative treatments like cognitive behavioral therapy, which has solid scientific evidence behind it.

In fact, AA and 12-step treatment appear to work better in terms of producing abstinence from alcohol. And some studies indicate that they lead to cost savings. (AA meetings, after all, are free.)

“From a public health standpoint, this is good news, because it means that we got a freebie out there that works,” John Kelly, a researcher at Harvard who led the Cochrane review, told me.

The new review, which looked at 27 studies involving nearly 11,000 participants, builds on a previous one by Cochrane. That review, in 2006, concluded that no studies “unequivocally demonstrated the effectiveness of AA or [12-step facilitation treatment] approaches for reducing alcohol dependence or problems,” but that 12-step treatment fared about as well as other treatment programs. This time, the Cochrane review found, there was more solid evidence for the finding that AA and 12-step treatment work at least as well as alternatives, although the quality of the evidence still had a wide range from very low to high.

Kelly said that, based on the evidence, the positive findings probably aren’t a result of anything unique to AA or 12-step treatment, but the kinds of traits more broadly applicable to mutual help groups in general, particularly the ability to bring people together and shift their social networks to better favor recovery.

The major strength of AA, then, is that it’s everywhere, with thousands of meetings a day and millions of members. If alternative mutual help groups, like SMART Recovery or LifeRing Secular Recovery, were as available, Kelly suspects that they would work as well as AA — and could fill the remaining void for people who, for whatever reason, don’t do well in AA.

“I don’t think it’s something unique to AA, as if it’s got some sort of magic,” Kelly said. “It’s rather that the magic of AA is that it’s everywhere and mobilizes these therapeutic mechanisms in a very strong, socially supportive network of recovery support.”

A big caveat: Cochrane’s findings only apply to alcohol addiction. The evidence for whether AA and 12-step treatment work for other drugs is much weaker — even nonexistent in some areas.

Still, alcohol addiction is by far the most prominent kind of drug addiction in the US. Based on federal data, more than 20 million Americans 12 or older had a substance use disorder in 2018, and nearly 15 million of those had an alcohol use disorder. Excessive drinking alone is linked to 88,000 deaths each year, with that death toll rising in recent years. So AA and 12-step treatment’s potential effectiveness for some people with alcohol addiction is a big deal — potentially a lifesaver.

What Cochrane’s review of AA and 12-step treatment found

The Cochrane review looked at studies that analyzed the effects of AA or 12-step treatment. That includes the typical AA meeting, thousands of which happen in churches and treatment centers all over the US on a daily basis. It also includes the more formal treatment programs that facilitate the 12 steps by guiding people to AA — an approach that more than 70 percent of addiction treatment facilities in the US use, according to federal data.

The review included studies comparing AA or 12-step facilitation treatment to other kinds of treatment, like cognitive behavioral therapy and motivational enhancement therapy, and different ways of facilitating the 12 steps.

The researchers evaluated studies for methodological quality, then gauged how AA and 12-step treatment fared in terms of rates of continuous abstinence from alcohol, percentage of days abstinent, longest period of abstinence, drinking intensity, alcohol addiction severity, alcohol-related consequences, and cost-effectiveness. (In most addiction treatment in the US, full abstinence from drinking is the goal. But some favor a less restrictive approach, which the other metrics cover.)

The findings: AA and 12-step treatment seem better than other treatment approaches for continuous abstinence and percentage of days abstinent, while likely producing “substantial cost-saving benefits.” AA and 12-step treatment did about as well on the remaining measures.

Given that AA meetings are free, Kelly said the findings suggest AA and groups like it “are the closest thing in public health we have to a free lunch.”

The findings apply only to alcohol addiction. The review did not look at 12-step treatment’s benefits for other drugs. Although some studies have looked at this, there’s generally a lack of evidence for AA and the 12-step approach when it comes to other substances, including opioid addiction.

Even within alcohol addiction, an area in which there’s been much more research on AA, the evidence was often lacking — with evidence from the included studies and for tracked outcomes at times graded as “very low” or “low” quality. This makes it hard to put too much stock in some of the review’s findings for individual outcomes, although AA and 12-step treatment do seem to be effective on average and overall.

Kelly also cautioned that not all 12-step treatments are the same, so they shouldn’t all receive the same credit. Some of the research, for instance, found using motivational interviewing techniques to persuade people to go to AA may produce better outcomes than just describing AA and the 12 steps to patients.

The findings also don’t mean that AA and the 12 steps work for everyone. J. Scott Tonigan, a researcher at the University of New Mexico Center on Alcoholism, Substance Abuse, and Addictions, previously told me that there’s roughly a “rule of thirds”: About a third of people maintain recovery from alcohol addiction due to AA, another third get something out of AA but not enough for full recovery, and another third get nothing at all. That’s potentially two-thirds of people who can’t get into recovery solely through AA or 12-step treatment.

The review didn’t look at how and why AA and 12-step facilitation treatment work, but Kelly and other researchers have studied that question for years. Despite the 12 steps’ emphasis on spirituality — the final step invokes “a spiritual awakening” — researchers say spirituality actually isn’t the key component in general, even if it’s helpful for some individuals.

The power of AA and the 12 steps instead lies in how they shift social networks, bringing people who struggle with alcohol addiction together. That gives people an important outlet for discussing challenges and coping mechanisms related to addiction with others who can credibly relate to the struggle of getting into recovery, while also providing a social check on unwanted behaviors.

And AA meetings can do this all by being accessible over long periods of time, with AA meetings spread all over the country and some localities having dozens of meeting a day.

“Pure and simple, it links people to an indigenous, ubiquitous community resource,” Kelly said. “If you’re treating a chronic illness, you want to link people to something that can help sustain that gain made initially in treatment, but over time.”

Even if AA works for some, we still need alternatives

As positive as the findings are for the 12 steps, Kelly cautioned against using the review’s findings as proof that AA is a one-size-fits-all solution for alcohol addiction. The same thing that appears to work for AA — the rerouting of social networks — could, after all, work as well for other mutual help groups, like SMART and LifeRing, if they were just as common.

In fact, one study already suggested that’s the case: The research, published in 2018 in the Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, found that the three biggest alternative mutual help groups — SMART, LifeRing, and Women for Sobriety — perform about as well as 12-step programs. It’s only one study, but it’s a promising finding.

In an ideal world, people would be able to choose from a menu of mutual help groups to find their best way to recovery. Someone who wants a spiritual focus can go to AA, while someone who wants a more secular experience can go to LifeRing. Someone who wants to use medications for addiction, like naltrexone and acamprosate for alcohol or methadone and buprenorphine for opioids, may do better in SMART and LifeRing — since AA groups can be hostile, despite the scientific evidence, to medications. Or someone could prefer the style of one group for whatever other reason.

Still, the reality is that AA and other 12-step groups are much more common in the US. No matter where you live in the US, there’s a good chance you can find an AA or other 12-step meeting that week — maybe even dozens a day, making it especially easy to fit one into a busy schedule. That’s not true for the alternatives in most places.

This gets to a key failure of the addiction treatment system: It’s simply not filling the need from people who do not do well in AA or 12-step programs in general. Treatment programs in the US tend to use the 12 steps as a core philosophy, pushing people to AA meetings as a necessary part of treatment. But even if that works for some people — as Cochrane’s review demonstrates — it’s not going to work for everyone. The concern here is particularly acute for drugs besides alcohol, since there’s not even good evidence the 12 steps work for other substances.

I’ve heard this firsthand from people struggling with addiction: Emilie Cote struggled for years to find an addiction treatment program that worked for her, in large part because so many emphasized the 12 steps. “I had a really hard time with the whole God thing,” Cote, who’s “not religious at all,” previously told me. She eventually found help for her opioid and meth use disorders in a secular program that provided medications for addiction.

But as Cote and other people in recovery are always quick to tell me, what works for them may not work for others. Even medications, which are considered the gold standard for opioid addiction, don’t work or aren’t necessary for everyone. The ideal, then, is to have a bunch of tools ready to tackle each individual’s specific problems.

So the Cochrane review doesn’t prove that AA and the 12 steps work for everyone. But it does, at least, show that AA is one more evidence-based tool in the shed. As Kelly put it, “Now we have a good science base also on which to base those [AA] recommendations.”

Author: German Lopez

Read More