The beloved Cartoon Network series was a silly kids’ show, an epic fantasy, a stoner’s dream, and one of the best shows of its time.

After more than eight years of shenanigans involving candy people, alternate universes, vampires, nearly 3,000 wiki pages’ worth of lore, some highly unusual exclamations (“Mathematical!”), and bacon pancakes, Cartoon Network’s beloved Adventure Time is coming to a close.

Since its debut in 2010, the series has evolved into one of the most popular and influential programs in the channel’s history. Despite being first and foremost a kids’ show, it built a sizable fan base among older audiences and gained mounting psychological and even philosophical weight over its 10-season run. The September 3 series finale marks the end of an era in imagining new storytelling possibilities, not just for cartoons but for TV in general.

Adventure Time spans nearly 300 11-minute episodes involving hundreds of distinct characters — so it’s no easy feat to describe. But in brief, it takes place 1,000 years after a nuclear apocalypse known as the “Mushroom War” warps the Earth into a fantasy landscape; its main setting, the Land of Ooo, is populated by offbeat creatures and people made of candy, fire, or “lumpy space,” among other things.

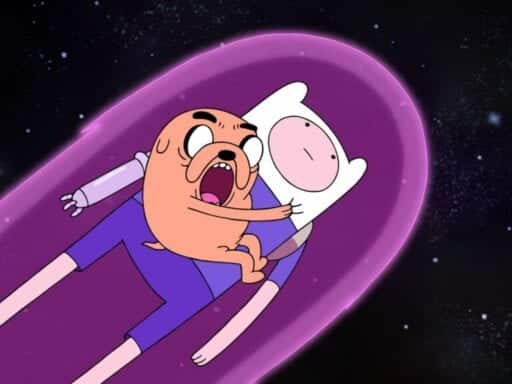

A young boy named Finn (Jeremy Shada) is apparently the last human being on the planet, and he and his foster brother/best friend — a shape-shifting dog named Jake (John DiMaggio) — have taken it upon themselves to be as helpful around Ooo as possible. They lend their treasure-hunting, monster-fighting, errand-running prowess to their many friends and neighbors, and along the way, the complex backstory of Adventure Time’s characters and their world is unspooled.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/12761383/Adventure_Time_Episode_260_Still.jpg)

That supremely odd summary belies the fact that Adventure Time has sneakily persisted as one of the most critically acclaimed shows of the 2010s. When considering the recent “Golden Age” of TV, few would rank it alongside the likes of Breaking Bad, Mad Men, or Game of Thrones. And yet it has received high praise from sources as wide-ranging as the A.V. Club, the New Yorker, NPR, and this very site.

In addition to being aimed at kids, Adventure Time lies at the intersection of multiple artistic categories that often struggle to attract serious critical consideration — namely, animation, fantasy, and short-form episodic TV (which for a long time was mainly the playground of experimental Adult Swim shows like Aqua Teen Hunger Force). Still, it has won over many critics. And though its erratic airing schedule has led to a decline in viewership and prestige in its later years, it has maintained a consistent standard of quality nonetheless.

With its series finale now on the horizon, let’s take a look back at the brilliance of Adventure Time, both as a singular achievement and as a show that has left a lasting impact on the TV landscape.

Throughout its run, Adventure Time was one of the most artistically adventurous shows on television

Adventure Time began as a short film made for Nicktoons. After the short leaked online and subsequently went viral, creator Pendleton Ward was able to successfully pitch it to Cartoon Network as a series. Produced in 2006, it exemplifies the “random” style of internet humor of that time, pioneered by the likes of Homestar Runner, eBaum’s World, and Newgrounds.

In just under seven minutes, a boy and his dog fight an ice-powered, princess-abducting king, with a brief dream excursion to Mars for a pep talk from Abraham Lincoln, before ultimately running off to confront some ninjas who have stolen an old man’s diamonds (ninjas were to internet comedy in the mid-2000s what bacon would be to it in the early 2010s). Millions of people loved it when it hit (the then-young) YouTube, and the short was eventually nominated for an Annie Award.

Once Adventure Time the show made its Cartoon Network debut, it found instant success and regularly drew millions of viewers per episode for many years. Examining the phenomenon, critics have often cited the show’s broad appeal for both kids and adults as a big reason for its popularity.

Cartoons have long embraced an anything-goes sensibility, but Adventure Time took the approach to a new level. Every single episode would pack its brief running time with strange new characters, places, and ideas: A vampire who drinks the color red. A pack of sentient balloons eager to die. An imaginative robot that “switches places” with its reflection. And to fit within the 11-minute runtime of each episode, it all came at the audience at a breathless pace.

Animated shorts are as old as television itself, but Adventure Time spurred a revival of the format, especially on Cartoon Network. The show also led the way in turning “random” humor and world-building from a niche interest into what is now practically an industry standard, not just for animated series aimed at kids but for adult-oriented ones as well. Shows like BoJack Horseman and Rick and Morty demonstrate a common willingness to indulge the strange, an instinct that Adventure Time arguably introduced to the mainstream.

It didn’t stop there. Even as Adventure Time told bizarre tales of trickster gods from Mars and penguins that turned out to be world-threatening alien abominations, it worked hard to incorporate them into its complicated backstory and world, maintaining dense continuity through multiple long-running story arcs. In the grand tradition of prestige TV, it featured overarching plots about Finn’s search for his birth parents, or the recurring threat of the fearsome undead sorcerer the Lich. And yet it also made time for many standalone episodes, sometimes ultimately folding them into the larger picture, with major characters like Marceline the Vampire Queen being introduced in apparent one-off installments.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/12761393/Adventure_Time_Episode_277_Still.jpg)

Adventure Time’s penchant for experimentation was both admirable and skillfully executed. The show didn’t hesitate to hand over multiple episodes to guest directors simply to riff on a different animation style. It occasionally adopted an idiosyncratic airing schedule, where several new episodes would drop over the course of a single week and then months would go by with nothing new. While the inconsistency sometimes hurt Adventure Time’s ratings, the show’s creative team used the “episode bomb” approach to produce several miniseries that featured some of its most ambitious ideas and set pieces.

Despite the show’s overall comedic tone, it handled its biggest ideas with gravitas and sincere emotion. And for all the manic energy it could indulge, Adventure Time never hesitated to slow down for a scene or two, or even a whole episode. American animation sometimes has trouble simply putting breathing space into shows and movies — superfluous gestures, brief pauses, and other moments that aren’t necessarily propelling the plot forward. Hayao Miyazaki once explained this to Roger Ebert as ma, the soundless beats between claps of the hand. Adventure Time had lots of ma.

Look at this scene from the “Stakes” miniseries, in the episode “Everything Stays.” In less than a minute, the episode creates an extraordinary evocation of intimacy between a parent and child. The animators inject dozens of little gestures to establish this feeling — note the brief shot in which young Marceline strokes her mother’s arm. And then the scene is over, and it’s on to the next beat.

This kind of formal economy, doing a lot in precious little time, is rare in television. Today, many prestige shows are running longer with each installment yet still struggle to carve out time for characters to simply be. They could learn something from Adventure Time, a show that used its 11-minute episodes to explore myriad genre ideas and flights of fancy, and to demonstrate the endless potential of simply being artistically open and flexible.

Adventure Time boasts more thoughtful character development and writing than most live-action shows

Every single character on Adventure Time, from the regulars to the one-episode guests, had a distinct voice. And I don’t mean in terms of acting (though the show’s voice acting was excellent), but in how each person spoke. The writers gave everyone a unique slang, or attitude, or cadence to work with.

Finn and Jake had their own adolescence-inflected goofy rapport and strange swears (“Aw, dingle!” “Algebraic!”). Marceline was a laid-back slacker punk rocker. Princess Bubblegum was officious and scientifically minded. Finn and Jake’s parents, who only appeared in a few episodes, had ’30s-style trans-Atlantic accents (“Make like there’s egg in your shoe and beat it!”). One episode set in an alternate universe introduced an entirely different future lingo. No character was too minor to be considered as a distinct individual.

Adventure Time frequently devoted entire episodes to fleshing out secondary characters, sometimes shining a spotlight on someone who had only existed in the background for the entire show up to that point. It drew up complex inner lives for the likes of characters with names like “Root Beer Guy” — a sentient, walking mug of soda — and “Cinnamon Bun.”

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/12761375/Adventure_Time_Episode_283_Still.jpg)

And what it could do for its main characters was even more impressive. Some of them were hundreds of years old, with a few of them predating the Mushroom War, and as we got to know them better, we came to understand a long history of regrets, which stemmed first from the act of survival and then from trying to build a new society out of the ruins. Their arcs were contrasted with the subtle but definable trajectories of Finn and Jake, who slowly matured over the course of the show from goofballs to responsible figures.

Many episodes of Adventure Time took detours to toss out different philosophical challenges, aiming them at both the characters and the audience. In one, Finn got trapped in another world and lived an entire lifetime there before returning to his own as a child again. In another, Finn and Jake confronted a population of people willingly submitting to a Matrix-like virtual reality existence. In a sequence emblematic of the series’ simultaneous whimsical tone and intellectual seriousness, one character mused: “What’s real? Your eyes think the sky is blue, but that’s just sun rays farting apart in the barf of our atmosphere. The sky is black.”

Adventure Time dared to be anything and everything, often at the same time. It was a silly, plotless kids’ show. It was an epic fantasy adventure. It was a long-term coming-of-age story. It was an experimental exercise. It was a stoner’s dream. It was a relationship drama. It was a heartbreaker.

Episodic television offers a canvas unique among the arts: time. The best shows make use of this canvas to tell their stories as creatively and ambitiously as they can; Adventure Time used it to become one of the best television series of its day.

Adventure Time’s four-part finale, “Come Along With Me,” airs Monday, September 3, on Cartoon Network.

Author: Dan Schindel