It starts with a nationwide rent-control initiative.

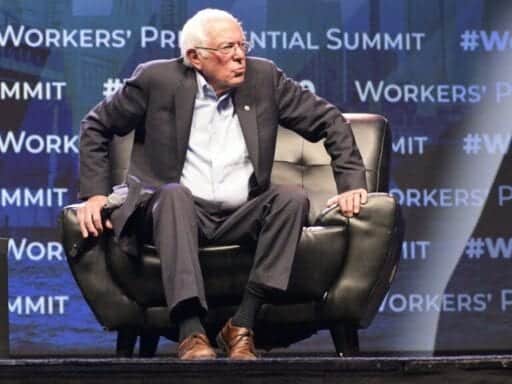

Democrats have rediscovered housing policy as a topic in the 2020 campaign cycle in a big way, and Bernie Sanders, who released an expansive affordable-housing agenda Tuesday, is no exception.

Many of the elements of Sanders’s “housing for all” agenda have clear echoes in other candidates’ proposals. Like Julián Castro, he calls for fully funding the Section 8 housing voucher program (Kamala Harris and Cory Booker have proposals that would accomplish something similar). Like Elizabeth Warren, he calls for a huge investment in building and maintaining subsidized housing units. And like a somewhat surprisingly wide array of Democrats this cycle, he calls for reforming zoning rules to allow for more construction in the priciest neighborhoods and markets.

But Sanders also stands out from the pack for his embrace of rent control, a long-out-of-style concept that’s making something of a comeback in liberal states. As is typical for Sanders, his rent-control proposal is much more sweeping and stringent than anything that’s been implemented anywhere, and it has some technical flaws.

This is, more or less, how Sanders likes to roll — flagrantly brushing aside wonkish worries that would get in the way of framing a good-versus-bad story and eager to attract criticism from technocrats that only serves to underscore his image as a unique scourge of the establishment.

Sanders proposes a 3 percent cap on rent increases

The Sanders rent-control proposal is mercifully simple compared to most real-world rent regulations. Annual rent increases will be capped at either 3 percent or 1.5 times the consumer price index (whichever is higher). There are none of the exceptions for vacant units, small-time landlords, new construction, or other lacunae that tend to sneak into these laws in places where they’ve been written.

The one small concession to the complexities of real life is the plan will “allow for landlords to apply for waivers if significant capital improvements are made, which will incentivize landlords to improve the conditions of their properties.”

But beyond that, it’s all very simple.

And while there are a lot of problems with this proposal, it also carries a very clear set of benefits. If you are a person who is currently renting and has no particular plans or desire to move, Sanders is giving you considerable insurance against the possibility of rent increases in your neighborhood — and if the neighborhood does become considerably more desirable and expensive over the next 10 years, you’ll end up inhabiting an apartment for considerably less than the prevailing market rent.

Other policy ideas that Democrats (including Sanders) have embraced, such as creating new housing supply through either public investment or regulatory reform, don’t have that quality. Lots of people are perfectly happy staying where they live, and they’d like to see the neighborhood get nicer without paying higher rent. If that’s your situation, Sanders delivers for you. And, more broadly, if you’re instinctively suspicious of market economics and the profit motive, Sanders cues into those values.

But the longer you think about how this is supposed to actually work, the more questions you’ll have.

This plan has some odd features

Start with the rent cap. Most new rent regulation proposals limit rent increases by some fixed amount above the overall rate of price inflation.

Oregon, for example, passed a law capping rent increases at CPI+7 percent per year. California earlier this summer enacted a similar law with a CPI+5 percent cap.

Sanders’s plan is much more stringent than that. The Federal Reserve is supposed to be aiming for inflation to average 2 percent over the long term, under which case Bernie would be capping rent increases at 3 percent — or 1 point over the rate of inflation. Recently, however, inflation has actually tended to run below the Fed’s 2 percent target, which under Bernie’s proposal means landlords would get a kind of minor windfall based on an unrelated monetary policy error.

But if the error went in the other direction instead and inflation went up, landlords could reap an even larger windfall — 10 percent annual inflation would allow for increases of 1.5 times 10 — 15 percent, or CPI+5 just like in California. Sanders’s discussion of his proposal doesn’t offer any explanation for how he arrived at the conclusion that the basic CPI+1 formula strikes an optimal balance and certainly not an explanation of why he thinks it makes sense to allow larger inflation-adjusted rent increases any time inflation drops either above or below the Fed’s target.

By the same token, while his plan does call for imposing a “just cause” requirement on evictions, there’s no language in the proposal protecting tenants from being displaced by landlords taking advantage of the capital improvements provision.

He also doesn’t say anything about how to allocate access to underpriced units that open up in hot markets. If you own a vacant apartment that has regulated rent far below the market price, you have a strong incentive to demand some kind of up-front payment from any tenant who wishes to lease it.

Most jurisdictions with strict rent-control laws attempt to ban this form of “key money” payment, generally with limited success. And if key money is successfully eliminated, it only creates a set of subsequent questions about landlords who only want to rent to friends of the family or on some kind of discriminatory basis. Trying to make a system like this work normally requires a fairly elaborate set of regulations and an enforcement apparatus.

Sanders, by contrast, seems to really just want to have an argument about rent control in principle rather than explain in a detailed way how it’s supposed to work.

Rent control is a problem if you want to move

The issue with rent control regulations is that while they generate large benefits for tenants who stay put in hot markets, they tend to make it a lot harder for people to find a new place to rent.

A recent study of rent control in San Francisco by economists Rebecca Diamond, Timothy McQuade, and Franklin Qian found that “landlords treated by rent control reduced rental housing supply by 15 percent, causing a 5.1 percent city-wide rent increase.”

People of a free market bent often say on this kind of basis that rent control “doesn’t work” or is counterproductive. But Diamond, McQuade, and Qian confirm that “rent control offered large benefits to covered tenants.” People renting apartments they like in neighborhoods they like and who want protection from the possibility of rent increases are not mistaken or deluded to believe that rent regulations could help them. It’s just that the cost to other people who’d like to move into a new place in San Francisco is high.

That group of potential movers includes children who grow up in the city and would like to get a place of their own, young couples who want to move into a bigger place before having a baby, would-be immigrants from foreign countries, newly broken-up couples, and of course people who’d just like to move to San Francisco to take a job in the booming local economy.

Rent control constricts the supply of rental housing through a number of different dimensions:

- By reducing the potential financial upside of building new rental housing, it generally discourages capital investment in the sector.

- By reducing the rental price of certain dwellings to below the market rate, it encourages owners to convert rental property into condos or owner-occupied dwellings.

- For similar reasons, it encourages the conversion of potential rental properties into Airbnbs or office space or some other form of real estate whose price is not regulated.

- By creating windfalls for long-time tenants in neighborhoods that have gotten expensive, it discourages empty-nest couples from downsizing and opening up family-sized dwellings for new families.

- For similar reasons, it discourages people who don’t actually value a suddenly in-demand location all that much from moving out and opening up space for people who do.

Housing policy has multiple dimensions, and while rent control helps one set of people it does so not just at the expense of a nefarious landlord class but at the expense of overall mobility. Ultimately to achieve the goal of “housing for all,” you do need to address the supply-side issue. When there aren’t enough units to go around then you can’t have housing for all.

Sanders also endorses a bunch of supply-side stuff

Rent control is clearly the flagship Sanders housing initiative.

It’s what he emphasized in his speech rolling out the plan and it’s what his team has emphasized on social media and elsewhere. This is the idea that sets him apart from the pack and the one that aligns him with righteous tenants’ activists over businesspeople and tedious wonks.

But Sanders does also call for investing $1.48 trillion over 10 years in the Affordable Housing Trust Fund while federally preempting local zoning regulations to force affluent communities to accept affordable housing projects. He calls for an additional $400 billion to be invested in building mixed-income projects under the auspices of the same trust fund. He also wants $3 billion in additional funds for tribal affordable housing projects and $500 million for rural affordable housing projects plus $70 billion to invest in upgrading existing public housing.

Then on top of all that, Sanders also embraces neoliberal-style deregulatory solutions. His plan says “restrictive zoning ordinances are a racist legacy of Jim Crow-era efforts to enforce segregation” and proposes making “federal housing and transportation funds contingent on remedying these zoning ordinances and coordinate with state and local officials and leaders to ensure equitable zoning.”

If you really did all that, you’d have a significant increase in housing supply that would offset many of the concerns about the impact of strict rent control. In the most expensive markets, the regulatory constraints of zoning are a much bigger deal than rent control, so if you lifted the one regulatory burden while imposing the other, you’d still get a net increase in the number of units. Pair those market-based measures with the vast scale of Sanders’s proposed expansion of affordable housing construction and increased subsidies for low-income renters, and you’d really be doing a lot on the supply side along with the rent control.

Fundamentally, however, the main thrust of Sanders’s thinking on housing appears to be anti-market — other provisions include a call for a stiff new tax on house-flippers, an expansion of inclusionary zoning regulations, and a special tax on vacant properties — even as he remains formally committed to a sweeping zoning reform that the candidate does not seem particularly interested in talking about.

All campaign documents of this sort are in some sense closer to fantasies than real policy blueprints but they tell us something about how candidates are thinking of issues. Sanders’ overall sense of housing — fitting his overall politics — is much more that the problem is one of under-regulation rather than over-regulation. He sees the bad guys as landlords and speculators rather than the millions of more or less ordinary homeowners whose localized “not in my backyard” attitude to new construction is in fact the main impediment to creating abundant housing in America.

Still, the fact that even a hardened market skeptic like Sanders is formally on board with the need for zoning reform and expansion of the housing supply is a real sign of how rapidly this topic has moved into the political mainstream — even as the candidate clearly seems more interested in going to war with technocrats over rent control.

Author: Matthew Yglesias

Read More