The Vermont Senator’s plan has lots of details about what single-payer would cover. It has less information on how to pay for it.

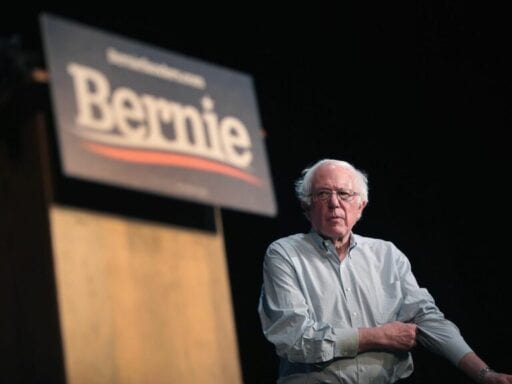

Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-VT) will reintroduce his plan Wednesday morning to transition the United States to a single-payer health care system, one where a single government-run plan provides insurance coverage to all Americans.

The Sanders plan envisions a future in which all Americans have health coverage and pay nothing out of pocket when they visit the doctor. His plan, the Medicare for All Act, describes a benefit package that is more generous than what other single-payer countries, like Canada, currently offer their residents and includes new income taxes on both employees and employers.

Sanders is reintroducing his plan at a moment when both American voters and Democratic legislators are increasingly backing a government-run health care system. Sanders will introduce his bill today with 14 cosponsors including presidential candidates Elizabeth Warren (D-MA), Cory Booker (D-NJ), Kamala Harris (D-CA), and Kirsten Gillibrand (D-NY).

The Sanders plan goes into great detail about the type of coverage Americans would receive. But it provides significantly less detail about how it would finance such a generous health care system. Instead, Sanders released a five-page paper that included a list of financing options, such as a new tax on “extreme wealth.”

Americans’ taxes would have to change to pay for this kind of proposal. But it’s impossible to tell who would pay significantly more for their coverage and who would pay less, and by how much. This is a crucial part of any health care plan, and in the Sanders proposal, it is notably absent.

So while the plan would move the American uninsured rate from around 8.8 percent to, in theory, nearly zero, it’s impossible to tell what it would take to get there and what the bigger economic picture would look like if we did.

The Sanders bill includes an exceptionally generous benefit package

Sanders’s single-payer proposal would create a universal Medicare program that covers all American residents in one government-run health plan.

It would bar employers from offering separate plans that compete with this new, government-run option. It would largely sunset Medicare and Medicaid, transitioning their enrollees into the new universal plan. It would, however, allow two existing health systems to continue to operate as they do now: the Veterans Affairs health system and the Indian Health Services.

Those who qualify for the new universal Medicare plan would get four years to transition into the new coverage. In the interim, they would have the option to buy into Medicare or another publicly run option that does not currently exist.

Eventually, though, they would all end up in the same plan, which includes an especially robust set of benefits. It would cover hospital visits, primary care, medical devices, lab services, maternity care, and prescription drugs as well as vision and dental benefits.

The biggest difference between this plan and the version Sanders introduced in 2017 is the addition of a long-term care benefit that would cover care for Americans with disability at home or in community settings. This benefit was also added into the House version of the Medicare-for-all bill earlier this year.

The plan is significantly more generous than the single-payer plans run by America’s peer countries. The Canadian health care system, for example, does not cover vision or dental care, prescription drugs, rehabilitative services, or home health services. Instead, two-thirds of Canadians take out private insurance policies to cover these benefits. The Netherlands has a similar set of benefits (it also excludes dental and vision care), as does Australia.

What’s more, the Sanders plan does not subject consumers to any out-of-pocket spending on health aside from prescriptions drugs. This means there would be no charge when you go to the doctor, no copayments when you visit the emergency room. All those services would be covered fully by the universal Medicare plan.

This, too, is out of line with many international single-payer systems, which often require some payment for seeking most services. Taiwan’s single-payer system charges patients when they visit the doctor or the hospital (although it includes an exemption for low-income patients). In Australia, people pay 15 percent of the cost of their visit with any specialty doctor.

The Sanders plan is more generous than the plans Americans currently receive at work, too. Most employer-sponsored plans last year had a deductible of more than $1,000. It is more generous than the current Medicare program, which covers Americans over 65 and has seniors pay 20 percent of their doctor visit costs even after they meet their deductibles.

Medicare, employer coverage, and these other countries show that nearly every insurance scheme we’re familiar with covers a smaller set of benefits with more out-of-pocket spending on the part of citizens. Private insurance plans often spring up to fill these gaps (in Canada, for example, vision and dental insurance is often sponsored by employers, much like in the United States).

The reason they went this way is clear: It’s cheaper to run a health plan with fewer benefits. The plan Sanders proposes has no analog among the single-payer systems that currently exist. By covering a more comprehensive set of benefits and asking no cost sharing of enrollees, it is likely to cost the government significantly more than programs other countries have adopted.

Would Sanders’s health plan lower American health spending? It’s hard to tell.

One of Sanders’s main arguments in favor of his health care bill is that American health spending is out of control and single-payer would rein it in.

“There is broad consensus — from conservative to progressive economists — that the Senate Medicare for All bill, as written, would result in substantial savings to the American people,” a paper released by his office argues.

There are certainly policies in the Sanders plan that would reduce American health care spending. For one, moving all Americans on to one health plan would reduce the administrative waste in our health care system in the long run.

American doctors spend lots of money dealing with insurers because there are thousands of them, each negotiating their own rate with every hospital and doctor. An appendectomy, for example, can cost anywhere from $1,529 to $186,955, depending on how good of a deal an insurer can get from a hospital.

That doesn’t happen in a single-payer system like the one Sanders proposes. Instead of dealing with dozens of insurers that set hundreds of prices, doctors only need to send bills to the federal government.

One 2003 article in the New England Journal of Medicine estimates that the United States spends twice as much on administrative costs as Canada. A 2011 study in the journal Health Affairs estimates American doctors spend four times as much dealing with insurance companies compared with Canada.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/16022154/figure_1_cap.png)

A single-payer health plan would have the authority to set one price for each service; an appendectomy, for example, would no longer vary so wildly from one hospital to another. Instead, the Sanders plan envisions using current Medicare rates as the new standard price for medical services in the United States.

Medicare typically has lower prices than those charged by private insurance plans that cover Americans under 65. This suggests that switching to the Medicare fee schedule would be another policy change that would tug health spending downward.

But there are forces in the Sanders plan that encourage higher health spending, too. Its robust benefit package with no cost sharing would likely lead to more doctor visits and hospital trips. As the classic RAND Health Insurance Experiment found, patients respond to lower cost sharing in health care by seeking more treatment. Some of that treatment is necessary, but other services provided are not.

And the Sanders bill would actually raise the prices currently paid by Medicaid, which covers about 50 million low-income Americans. Medicaid traditionally pays lower prices than Medicare and private insurance. If these patients were absorbed into the universal Medicare plan, their doctors would be paid more each time they were seen.

We haven’t seen a Congressional Budget Office score of the Sanders plan yet — and it’s hard to know how these countervailing forces (some pushing health spending up and others forcing it down) would interact with one another to change overall health costs.

The big question Sanders doesn’t answer: How do you pay for it?

The Sanders plan goes into great detail on what kind of coverage a universal plan ought to offer. But it does significantly less work explaining how this would be paid for. Instead, Sanders’s office released a paper that included this bullet-point list of possible options:

- Creating a 4 percent income-based premium paid by employees, exempting the first $29,000 in income for a family of four

- Imposing a 7.5 percent income-based premium paid by employers, exempting the first $2 million in payroll

- Eliminating health tax expenditures

- Making the federal income tax more progressive, including a marginal tax rate of up to 70 percent on those making above $10 million

- Making the estate tax more progressive, including a 77 percent top rate on an inheritance above $1 billion

- Establishing a tax on extreme wealth

- Closing a tax-loophole that allows self-employed people to avoid paying certain taxes by creating an S corporation

- Imposing a fee on large financial institution

- Repealing corporate accounting gimmicks

The items on this list could no doubt be used to finance a national health care system. But eventually, someone is going to have to pick which items on this list become law — and that’s where things get tough.

Financing the health care system that Sanders envisions is an immense challenge. About half of the countries that attempt to build single-payer systems fail. That’s Harvard health economist William Hsiao’s estimate after working with about 10 governments in the past two decades. Whether he is in Taiwan, Cyprus, or Vermont, the process is roughly the same: Meet with legislators, draw up a plan, write legislation. Only half of those bills actually become law. The part where it collapses is, inevitably, when the country has to pay for it.

This is what happened when Sanders’s home state of Vermont attempted to create a single-payer plan in 2014. Much like Sanders, local legislators outlined a clear vision of the type of health plan they’d want to extend to all Vermonters. Their plan was arguably less ambitious; it did require patients to pay money when they went to the doctor.

But Vermont’s single-payer dream fell apart when the state figured out how much it would need to raise taxes to finance its new system. Vermont abandoned the government-run plan after finding it would need to increase payroll taxes by 11.5 percent and income tax by 9 percent.

It’s true — in Vermont and in the United States — that these increased taxes don’t necessarily mean overall health spending is rising. It’s entirely possible that health spending will go down as taxes go up, with Americans no longer spending billions on premiums for employer-sponsored coverage.

Single-payer systems change who pays for health care, often shifting more of the burden onto wealthier individuals to create a more progressive system. The proposed 9 percent income tax in Vermont, for example, would be far more expensive for the $100,000 worker than the $30,000 earner.

But who pays how much more is a key question this Sanders bill doesn’t answer yet. Until there is a version that does, we can’t know whether the health system the Vermont senator envisions could actually become reality.

Author: Sarah Kliff

Read More