Bernie Sanders has a plan to give workers ownership at their companies.

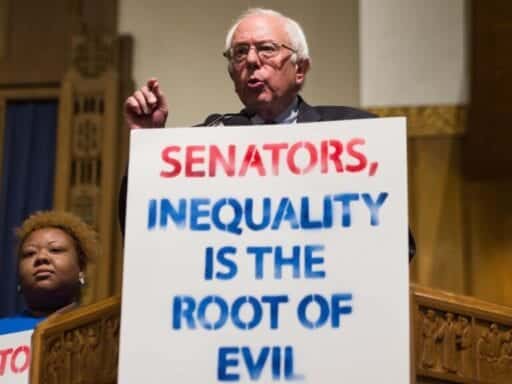

Bernie Sanders’s return to the campaign trail will come with a renewed message about the need to reform corporate America — and it will be backed by a comprehensive proposal to significantly transfer power to workers in the American economy.

Ahead of the fourth Democratic presidential debate, which will be Sanders’s first campaign appearance since suffering a heart attack on the trail two weeks ago, the Vermont senator’s campaign unveiled its “Corporate Accountability and Democracy” plan Monday. In broad strokes, the plan calls for giving workers ownership stakes in their companies, reversing major corporate mergers, and undoing the Trump administration’s corporate tax cuts.

Sanders has teased parts of this plan in the press previously, touching on themes Sen. Elizabeth Warren has raised about breaking up big tech, giving workers a seat at the table on corporate boards, and increasing taxes on corporations. But in Sanders style, this plan significantly broadens the scope of the conversation about corporate reform. It’s big.

Asked over the weekend how he differentiates himself with Warren, Sanders told ABC, “Elizabeth considers herself—if I got the quote correctly—to be a capitalist to her bones. I don’t. And the reason I am not is because I will not tolerate for one second the kind of greed and corruption and income and wealth inequality and so much suffering that is going on in this country today, which is unnecessary.”

Sanders has long advocated for curbing rampant inequality with a robust social welfare state, including tuition-free college and Medicare-for-all, paid for by significant tax increases on the wealthy and corporations. In this plan for corporate accountability he’s laying out the groundwork different kind of economy all together.

“This is the most ambitious plan on corporate ownership ever put out by a presidential candidate,” Peter Gowan, with the Democracy Collaborative, an economic inequality-focused research institution, said. “[This is] giving real bones to Sanders’ vision of democratic socialism.”

Bernie wants workers to own a share of the companies they work for

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19284732/1171035310.jpg.jpg) Bill Pugliano/Getty Images

Bill Pugliano/Getty ImagesThe centerpiece of Sanders’s Corporate Accountability Plan is a proposal to shift power to workers by requiring all large companies — those with at least $100 million in annual revenue, and all publicly traded companies — to come under partial employee-ownership.

The idea is to require large companies to contribute 2 percent of their stocks annually to a employee-controlled fund until workers control 20 percent of the company, and then pay out the dividends to those workers. The campaign estimates the plan would impact 56 million workers at more than 22,000 companies in the United States.

Those funds — dubbed Democratic Employee Ownership Funds — would be controlled by an employee-elected board of trustees, and the workers benefiting from them would have the same voting rights as any other shareholder in the company.

This is an idea that’s been backed most prominently by the United Kingdom’s left-wing Labour Party, which called for the establishment of an “Inclusive Ownership Fund,” with workers possessing 10 percent of company equity in all companies with more than 250 employees. Lenore Palladino, a senior economist at the Roosevelt Institute, published research finding that the Labour Party’s proposal would result in nearly an additional $2,725 per year for the average worker. Sanders campaign estimates their proposal would result in an average dividend payment of over $5,000 per worker every year.

Sanders is pairing this idea with a slate of other proposals to give employees more power at their companies:

- He’s calling for codetermination, requiring 45 percent of large companies’ boards to be employee-elected. This is similar to Warren’s business reform plan, which calls for employees to elect 40 percent of company boards.

- As with Warren’s proposal, he also wants to create a Bureau of Corporate Governance at the Department of Commerce, where large companies must go to get federal charters requiring them to follow rules around corporate responsibility.

- Sanders wants to ban stock buybacks, the practice where a company buys back its own shares from the marketplace. Sanders had previously proposed, with Sen. Chuck Schumer (D-NY), allowing buybacks only if companies first paid their workers more, increased benefits, and secured pensions. (His campaign has not yet confirmed whether the Senator still supports that proposal with Schumer)

- He proposes giving workers the right to buy a company if it goes up for sale, is closing, or moving overseas — a transition made easier if employees already hold a 20 percent stake in the company.

- And he wants to establish a $500 million US Employee Ownership Bank to give workers who want to purchase businesses low-interest loans and loan guarantees.

Overall, this proposal could have enormous impact on the current makeup of the US economy. A Rutgers University study on employee ownership found that employee stock ownership plans have been successful in increasing workers’ assets and in closing racial and gender wealth gaps in the workplace. And research from countries like Germany, which have codetermination policies in place, have much higher levels of pay equality, and have seen positive results on productivity and innovation.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19284733/1171035068.jpg.jpg) Bill Pugliano/Getty Images

Bill Pugliano/Getty ImagesAs Matt Yglesias explained for Vox, the current makeup of stock ownership has exacerbated inequality in the United States.

Since 80 percent of the value of the stock market is owned by about 10 percent of the population and half of Americans own no stock at all, [rapidly increasing stock prices] has been a huge triumph for the rich. Meanwhile, CEO pay has soared as executive compensation has been redesigned to incentivize shareholder gains, and the CEOs have delivered. Gains for shareholders and greater inequality in pay has led to a generation of median compensation lagging far behind economy-wide productivity, with higher pay mostly captured by a relatively small number of people rather than being broadly shared. Investment, however, has not soared. In fact, it’s stagnated.

It it this sort of inequality Sanders hopes to combat with his plan, and Gowan argues it could go a long way towards reversing increasing inequality in the US.

“Really what this is all this adds up to is a massive redistribution of wealth and power, but it gives employees a bunch of tools to turn their companies into employee owned models,” Gowan said.

This plan calls for a retroactive reversal of major corporate mergers

In the early 1980s, the United States’ Federal Trade Commission changed the way it approached major mergers; it no longer cared how big of a market share the newly formed companies would have if they merged, or if there would be a monopoly. The name of the game became “consumer welfare” — a standard defined by whether economists believed the merger would bring prices down for consumers.

Sanders wants to wind back the clock 40 years, and reestablish market shares as the determining factor in approving or rejecting mergers. His reasoning is a scathing indictment of the FTC, which his campaign argues has stopped being a regulatory body, and has instead used the consumer welfare standard to allow for unfettered corruption, and monopolies that hold back innovation and price gouge American people.

“The FTC has lost its credibility as a regulatory agency,” the plan reads. “Bernie will appoint commissioners who serve the public interest and will end the revolving door of FTC commissioners and staff leaving to work for the very same corporations they were previously in charge of regulating.”

Sanders also argues the current merger rules are leaving Americans out of work. As examples, his campaign cites a 2018 merger between two mortgage loan companies in Iowa, Ocwen Financial and PHH, that resulted in 2,100 employees being laid off. And it points to a merger this year, when Dominion Energy purchased South Carolina utility SCE&G, and announced buyouts for 1,200 workers, with the expectation that hundred will be laid off.

The shift to a new merger standard is a substantial one — and his campaign also sees it as retroactive, calling for a review of all mergers under the Trump administration. It could mean hundreds of companies would be forced to reorganize. While such a plan seems like it would be opposed by the business community in general, Matt Stoller, an antitrust expert with Open Markets Institute, said that isn’t necessarily the case.

“Saying that the FTC has failed its mission and lost its credibility as a regulatory agency is important,” Stoller said. “Bernie is coming out with a progressive platform to address monopolies, but it is actually pro-business platform. … A lot of the pressure from the FTC is coming from the business community.”

Businesspeople are exerting this pressure on the FTC, Stoller says, because there are many who feel their companies have been squashed by monopolistic entities. So while multinational firms may fight back against this part of Sanders’s proposal, smaller firms may welcome it.

And retroactively breaking up companies is not completely unprecedented. In 1960, for example, a 1957 merger between Proctor and Gamble and Clorox was ruled in violation of antitrust law, and the two were forced to break up. Undoing decades of mergers won’t be easy, but Sanders believes it is doable despite the legal challenges that such a move would no doubt face.

Sanders wants to undo the Trump corporate tax cuts

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/9946301/896237194.jpg.jpg) Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images

Chip Somodevilla/Getty ImagesSanders, like most Democrats in Congress, has been a vocal critic of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act Trump signed into law in late 2017. With this plan, he promises to undo the changes that act made to the tax code that gave a massive windfall to corporations.

His plan calls for restoring the corporate tax rate to 35 percent, where it was before Trump’s cut brought it down to the current 21 percent. That tax rate would be the same rate for overseas and domestic income.

“Sanders, for the longest time, the one thing that has been his push is to go to this full worldwide tax system,” Kyle Pomerleau, with the Tax Foundation said. “He proposed that in 2016 and he is really committed to that reform.”

In a worldwide corporate tax system, corporations are taxed on their earnings in total, whether they are made offshore or domestically. Currently, global profits are taxed when they are brought back to the United States and spent or invested. The idea behind a worldwide system, as Vox’s Dylan Matthews has previously explained, is to “reduce the risk of companies misclassifying income as being earned abroad (since income earned abroad is still taxed).”

But as Pomerleau points out, Sanders’ proposal could also encourage companies to relocate to other countries, or to attempt to pay lower taxes through corporate inversion. While Sanders’s proposal addresses this phenomenon with strict rules around interest deductions, Pomerleau says Sanders’s rules don’t account for new businesses looking to incorporate that are? interested in cheaper tax rates abroad.

Despite this, Sanders’s campaign maintains that the proposal would be broadly beneficial in raising tax revenues — it claims if the plan were currently law, Amazon’s taxes would have been $3.8 billion last year. Chevron would have paid up to $1.6 billion in taxes. In total, should it operate as projected, the change would raise $3 trillion in revenue.

The plan also calls for eliminating the 20 percent deduction pass-through entities — companies organized as sole proprietorships, LLCs, partnerships, and S corporations — get on their business income.

The deduction for pass-throughs is seen as one of the major loopholes in the Republican tax cuts. It was written in an attempt to make small businesses more competitive with corporations, but it has become a way for the wealthy to obfuscate their actual personal income.

In the end, the plan is standard “Sanders fare,” Pomerleau said. Sanders’s vision for the American tax code lays out what Americans consistently cite as their biggest gripe with the the tax code: that corporations don’t pay their fair share.

Should Sanders become president, this corporate accountability plan will likely be a top priority; there is little of it that can be done without the cooperation of Congress, however. The president can shape their Federal Trade Commission, but cannot rewrite tax code, for example.

Nevertheless, this plan captures the ideas and ideology at the center of Sanders’s campaign: That workers need more power and protections and that corporations need to bear more responsibility for improving the society in which they operate.

Author: Tara Golshan

Read More