The mix of slapstick, situational humor, and heartfelt affection (or sometimes winking homoeroticism) that usually powers the buddy comedy is best suited for lighthearted ruminations on the nature of friendship, often between men; it isn’t typically deployed in the service of broader social commentary.

But the creative duo behind Blindspotting — lifelong friends Rafael Casal and Daveed Diggs, who wrote the film and star as lifelong friends in it — saw potential in both the genre and their lived experiences to say something about race, both in their hometown of Oakland and in the broader American conversation. Casal is white and Diggs is black. Casal is a performance poet and Diggs is a rapper. And both men felt there was something to be gained by combining comedy with commentary.

It took the pair about 10 years to turn their ideas into a movie, and in the intervening years between Blindspotting’s conception and its Sundance debut this past January, Diggs — who electrified audiences and gained a huge following when he originated the roles of Thomas Jefferson and the Marquis de Lafayette in the hit musical Hamilton — became a star.

All that helped to raise the film’s profile as it comes out in a cultural moment defined by a heightened awareness of the complicated matters of race, class, police violence, and gentrification. Now seems like exactly the right time for movies to tackle these themes, and first-time feature director Carlos López Estrada shapes Blindspotting’s interpretation of them into a rhythmic, hilarious, deeply felt mixture of hard truth and real life.

Ariel Nava/Lionsgate

Ariel Nava/LionsgateBlindspotting tells the story of two friends whose relationship comes to a head in three harrowing days

Blindspotting’s title comes from a term that one of its characters, psychology student Val (Janina Gavankar), comes up with to describe the phenomenon in which a person sees only what they want to see while neglecting to see what’s in their blind spot. “You’re always gonna be instinctually blind to the spot you’re not seeing,” she tells Collin (Diggs), her ex-boyfriend and co-worker at a moving company where he hauls boxes and she manages workflow.

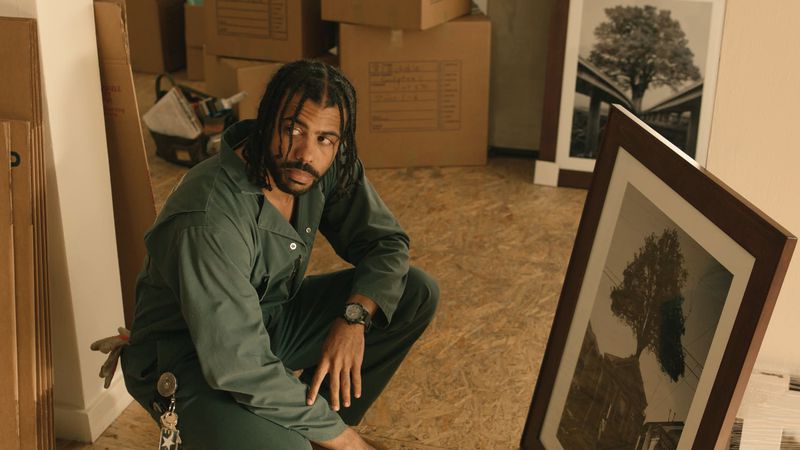

Collin and Val broke up when he went to jail for assault following an altercation with a white hipster outside the Oakland bar where Collin used to be a bouncer. Now, after two months in jail and just about a year of parole in a halfway house, Collin is three days short of being a free man, albeit one on probation.

Ariel Nava/Lionsgate

Ariel Nava/LionsgateDuring his year on parole, he’s been working side by side with his best friend Miles (Casal). The two have been friends since they were 11, and if there’s one thing they love, it’s their hometown of Oakland. Collin wears dreads; Miles sports a collection of tattoos and a grill. Collin spends a lot of time at Miles’s house, where Miles lives with his girlfriend Ashley (Diggs’s fellow Hamilton alum Jasmine Cephas Jones) and their young son.

But for the past year, Collin has been required to spend his nights at the halfway house, and to follow a curfew. And now he only has three days left, which means he’s desperate to stay out of any inadvertent trouble.

Tragically, while rushing back to make curfew, he witnesses the unthinkable: a black man, fleeing a cop on foot, gets shot four times in the back and dies. The incident haunts Collin, and — along with a few close scrapes and painful realizations — kicks off a few days that will change not just Collin’s life, but the landscape of Collin and Miles’s friendship, too, as their own long-ignored blind spots begin to surface and threaten to tear apart their relationship.

Blindspotting incisively captures the absurdity and complexity of a rapidly changing Bay Area

Casal’s and Diggs’s reputations as wordsmiths precede them; the two were founding members of the collaborative hip-hop ensemble the GetBack, and have worked together musically in a number of contexts.

Blindspotting is thus laced with wordplay, at times spinning out into full-on freestyling, and this furnishes some of the most memorable moments in the film (including its ending). It’s in keeping with the movie’s feeling of heightened reality, and occasional surreality — something it shares with another socially conscious Oakland-set comedy out this summer, rapper Boots Riley’s Sorry to Bother You.

Both films are very mindfully set in the rapidly changing Bay Area, where the juxtaposition of old and new, particularly given some of the goofier hipster excesses on display, contribute to the feeling of surreality, and both films capture that feeling by dialing it up a notch or two.

Ariel Nava/Lionsgate

Ariel Nava/LionsgateCollin and Miles’s relationship also allows the movie to carefully but confidently address some of the thornier realities that abstracted political and social arguments often sidestep for convenience’s sake. Why does the shooting affect Collin so much, while Miles seems to brush it off more easily? Why is Miles so explosively angry over the influx of hipsters into his neighborhood, while Collin can’t muster the same response? For two men who are so very alike, where do the differences really lie?

It’s questions like these that Blindspotting asks with an obvious air of knowing exactly what the hell it’s talking about, and the result is some real earnestness mixed in with a lot of excellent jokes (like a relaunched burger place that requires meat-eating customers to specify they want a meat patty when they order, because the default is vegan).

The film constantly forces Collin and Miles to look one another in the face — first playfully, then more forcefully — to remind us that we can know a person for a long time but never really see them. There’s also a lot in the film about race- and class-based coding; the assumptions people make about their neighbors; gun violence; the relationship between black residents and the cops who all live out of town; and a lot more.

Ariel Nava/Lionsgate

Ariel Nava/LionsgateAt times it feels a tad hamfisted. You can occasionally see the think piece lurking beneath the conversation.

But couched in a buddy comedy, I think it pretty much works. As evidenced by some of the best sitcoms on TV right now — like One Day At A Time, Superstore, and Black-ish, in which Diggs has a recurring guest role — comedy can be a vehicle for commentary on matters that are deadly serious not just off-screen, but to the characters we’re watching.

There’s a time and a place for everything, but with the stakes this high, the kind of sincerity and passion that pervades Blindspotting’s buddy comedy setup feels real and merited. And like any good buddy comedy, it reserves plenty of space for some grade-A slapstick fun. The film is a confident debut from two writers and a director with no shortage of things to say and a strong voice to say them in.

Blindspotting opens in theaters on July 20.

Read More

https://cdn.vox-cdn.com/community_logos/52517/voxv.png