The controversy over Woodward’s new book Rage is part of a larger debate over journalistic ethics.

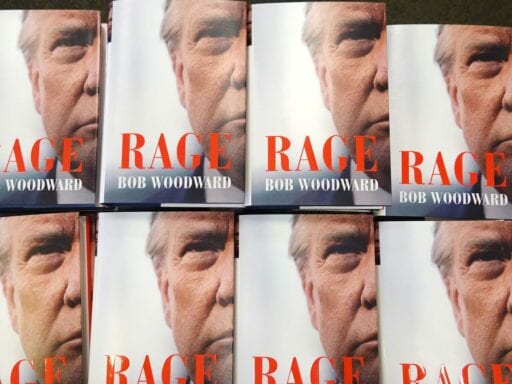

Bob Woodward’s new Trump exposé, Rage, promised to deliver bombshells. And it did. As publisher Simon & Schuster prepared to release the book on September 15, a revelation hit the news that was actually shocking: Woodward announced that Trump knew as early as February that the Covid-19 pandemic was a lot more serious than he let on publicly — and Woodward had the tapes to prove it.

That revelation set off a storm of fury at Trump. But it has also led to questions about Woodward himself, and the way he chose to report on the president.

“This is deadly stuff,” Trump told Woodward on February 7, adding that he knew the virus was “airborne.” Yet as late as March, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention was advising Americans to focus on washing their hands to prevent the spread of the virus, rather than to think about ventilation. Trump declared on February 27 that the virus would soon disappear “like a miracle.”

On March 19, Trump told Woodward that the illness could attack the young as well as the old; a few months later, during a public briefing in July, he declared that young people were “almost immune” to the disease. It was also on March 19 that Trump told Woodward he was intentionally “playing down” the threat of the virus in public, because “I don’t want to create a panic.”

Trump’s policies in response to the pandemic have been a clear failure with regard to public health and the safety and economic security of all Americans. But he has additionally failed anyone who believes in him because of his status and office. The president of the United States told people they were safe in situations he knew to be unsafe, and as a result, he placed them in danger.

Take, for instance, Kristin Urquiza, who spoke at the Democratic National Convention in August. Her father, Mark Anthony Urquiza, a Trump supporter, died of Covid-19 after going to a bar, citing Trump’s urging to “get out and about.”

“My dad was a healthy 65-year-old,” Urquiza said. “His only preexisting condition was trusting Donald Trump, and for that he paid with his life.”

The backlash against Trump in response to the revelations of Rage was fierce and swift. But another backlash against Woodward soon followed.

If Woodward knew that Trump knew Covid-19 was deadly serious, critics asked, why did he wait so long to tell the country? Wasn’t it possible that revealing the truth earlier could have saved lives? If people like Mark Anthony Urquiza had learned that Trump was deliberately lying to them, might they have changed their behavior?

Of course, learning what Trump was saying in private might not have made a difference to his supporters. It’s impossible to know for sure. But is it a journalist’s responsibility to give the public information that is relevant to their safety in a timely manner, even knowing the public might choose to ignore it?

Put simply: Did Woodward have a journalistic imperative to make what he knew public as soon as possible, in a daily newspaper, rather than waiting until he could publish it in a book from which he would personally profit?

“There’s that classic J-school ethics class problem, ‘What if a source tells you about a nuclear attack in 24 hours, off the record — what are you going to you do?’” says Bill Grueskin, a professor at the Columbia School of Journalism. “I don’t think there’s that much question. You try to save a million people.”

For many observers in the media, the decision that Woodward and Simon & Schuster made to withhold information on Trump’s lies was the equivalent of failing to tell the country about a nuclear attack.

The resulting debate speaks to a larger set of questions that have emerged as a series of book-length exposés about Trump have taken over the best-seller lists throughout the past three years: When does a scoop belong in a book, and when does it belong in a newspaper? What is the role of the nonfiction book in journalism? And what kind of responsibility do journalists, publishers, and booksellers have toward their audience in a time of crisis?

It took until May for Woodward to determine that Trump was telling him the truth. What happened afterward is more complicated.

The debate over Woodward’s journalistic choices began almost immediately after he published his first excerpt.

“Why are we learning about it in a book published in September? Isn’t there a journalistic imperative to publish this information in a timely manner… especially during a pandemic?” tweeted Adweek’s Scott Nover.

“Woodward knew the truth behind the administration’s deadly bungling,” wrote Charles P. Finch at Esquire, “and he saved it for his book, which will be released to wild acclaim and huge profits after nearly 200,000 Americans have died because neither Donald Trump nor Bob Woodward wanted to risk anything substantial to keep the country informed.”

And yet, “I don’t know if putting the book’s newsiest revelations out there in something closer to real time would have made a difference,” cautioned Margaret Sullivan at the Washington Post. “They might very well have been denied and soon forgotten in the constant rush of new scandals and lies.”

Still, Sullivan concluded, “the chance — even if it’s a slim chance — that those revelations could have saved lives is a powerful argument against waiting this long.”

Woodward has maintained that he believes he fulfilled his role as a journalist in the way he reported the story. “I think I have a public health responsibility, like any citizen does — or maybe a journalist has more of a responsibility,” he told NPR. “If at any point I had thought there’s something to tell the American people that they don’t know, I would do it.”

There’s a fairly straightforward explanation for a large chunk of the period in which Woodward kept his news about Trump to himself: When Trump first discussed the coronavirus with Woodward in February, Woodward had no way of knowing that what Trump told him in private was actually true.

“He tells me this, and I’m thinking, ‘Wow, that’s interesting, but is it true?’ Trump says things that don’t check out, right?” Woodward told the Associated Press.

“As Woodward describes it, he goes on a three-month repertorial bender, trying to nail down where Trump was told this, who he had been consulting with on his staff, and what meetings there had been,” the Washington Post reporter Erik Wemple, who spoke to Woodward, told Vox over the phone. It wasn’t until May that Woodward knew for sure that Trump’s information was good.

So then why not make his information public in May? asked Sullivan at the Post. That version of events would still have made the news public four months and nearly 100,000 deaths earlier.

Sullivan reported that Woodward told her he wanted to contextualize the information as fully as possible, and give his readers the best and most complete version of the story to read before Election Day.

To some observers, Woodward was doing just what journalistic book authors are supposed to do when he made that choice. Ideally, book publishing’s slow time frame and long-scale format should allow for more rigorous and complex reporting than fast-paced daily news coverage can reasonably accommodate. Woodward was just taking full advantage of the format to give his readers the most accurate version of the story he possibly could.

“I think journalists should publish when they’re ready, and a book author publishes when they finish their editing,” Wemple told Vox. “Writ large, it’s a real healthy thing that we have people working on different timelines in our democracy.”

Wemple argues that Woodward’s job is to do long-term, book-length investigative reporting, while plenty of other journalists do day-to-day breaking news coverage of Trump’s various lies and misdeeds. Wemple adds that the track record of those reports makes him doubt that anything Woodward might have reported early would have had a major public health effect.

“We have had millions of instances when Trump has lied and said contradictory things, day in, day out. Do those things move the needle? You can be the judge of that,” Wemple says. “Woodward is adding to our understanding. People are saying he should have done this back in March or April or whenever, and I respect that level of scrutiny. But I don’t think it’s the way a book author works.”

There are no hard-and-fast rules for how to decide what reporting should be saved for a book and what should be reported immediately, says Lynn Walsh, chair of the ethics committee for the Society of Professional Journalists. She notes that accuracy should always come before speed, and a journalist should always make certain to do their due diligence and be sure they are correct on the facts. But once those issues are covered, as they apparently were for Woodward by May, other concerns enter the picture.

“Information is power,” says Walsh. “We should not withhold information that could help a member of the public make decisions in their lives, especially ones impacting their health or safety.”

The Columbia School of Journalism’s Grueskin adds that it’s possible Woodward needed to preserve his access to Trump to continue doing the level of reporting he was doing. Woodward has said that he made Trump no promises about keeping their interviews under wraps until the book came out. Still, Grueskin points out, “There’s things people will tell you more candidly knowing it won’t show up for weeks or months, as opposed to it showing up on the website 20 minutes after you leave their office. I understand there’s a calculation there.”

But, Grueskin says, “Barring some underlying agreement with your source when you get something truly newsworthy on its own, especially one that has value for public health, you have a much greater responsibility to come out with it.”

Woodward has chosen in the past to immediately break stories he comes across while reporting a book. In 2009, while reporting a book on the Obama White House, he obtained a 66-page Pentagon report saying the US needed more troops in Afghanistan. Reasoning that the report’s recommendations would be “overtaken by events when the book comes out next year,” he decided to report on the scoop for the Washington Post instead.

That 2009 decision grants Woodward “more credibility on his rationale for not doing it this time,” says Grueskin. “But while that was important and valuable, public health concerns tend to trump everything else, and you have to be much more thoughtful about it.”

Maris Kreizman, a freelance journalist who covers publishing, argues that Woodward’s decision to hold his Trump story for the book he planned to publish during election season rather than publishing it in May was Woodward using the genre of the reported political book in exactly the way it’s not supposed to be used.

“Books have had revelations saved for their pub date for years and years,” Kreizman says. “But books have not been a primary news source, for the most part, ever.” She argues that that’s not the purpose books are meant to serve in the ecosystem of journalism.

Kreizman calls the more recent trend toward holding breaking news items for books “really disturbing,” because book publishing is such a slow process. Holding a major scoop until a book might be published means there’s a long gap between when a reporter learns of new information and when that information finally reaches the public. For Kreizman, that gap is immensely dangerous.

And while in theory the scale of a book offers a journalist the chance to be rigorous and thoughtful in their reporting and fact-checking, in practice, book publishers generally don’t offer any kind of infrastructure to help reporters be more rigorous in their work. In book publishing, the burden of fact-checking falls to the author. And because fact-checking is laborious and expensive, many of them decide to skip it.

Woodward does appear to fact-check his work, and he has already published the tape to back up the most dramatic of the revelations he writes about in Rage. There is no reason to doubt the accuracy of his reporting. But it also remains the case that there is nothing intrinsic to the process of publishing a book that would make Rage more reliable than a report that was published in a newspaper. “Just because a piece of journalism is slower doesn’t mean that it’s any more accurate or factually correct,” Kreizman says.

She argues that Rage publisher Simon & Schuster’s decision to hold the book until election season seems cynical and profit-motivated.

“Whatever happened with this book and Woodward’s intentions, there was a lot of planning on the part of Simon & Schuster about how best to sell this book,” Kreizman says. “And juicy revelations seem to be the thing that people want more than ever in a book they’re going to buy. The idea that they didn’t know in advance — maybe not in February, but in advance — that this book contained information that we needed seems ridiculous.”

Simon & Schuster declined to comment on this story, and Woodward did not respond to a request for comment. But if Simon & Schuster did make a marketing decision based on the public’s love for juicy revelations about Trump, the past few years of book publishing would have given the publisher plenty of data to use as the basis for its decision.

However, the past few years of book publishing would also have provided a case study in the weaknesses of book-length political reporting.

Book publishing doesn’t consider ethical questions to be its business. Increasingly, that’s a problem.

Publishing in the Trump era has been characterized by the release of big, splashy books that promise to expose all of Trump’s mendacity at last. Some of them are by public officials who have worked with Trump, like John Bolton’s The Room Where It Happened and Anonymous’s A Warning. Some of them are by political journalists who are profiling Trump, like Michael Wolff’s Fire and Fury and Michael Schmidt’s Donald Trump v. The United States. And there is money in these books. They tend to sell and sell and sell.

According to the industry tracker NPD BookScan, The Room Where It Happened has sold more than 650,000 copies since its publication in June. A Warning has sold more than 192,000 copies since it came out in November 2019. Fire and Fury (2018) outsold them all with over a million copies sold — but Woodward’s last Trump exposé, 2018’s Fear, came close, with 959,500 copies sold. Schmidt’s Donald Trump v. The United States, which dropped at the beginning of this month, is an outlier, with sales figures of only 17,200 units, but it’s only in the high-octane world of political exposés that those figures are middling. For most other publishing categories, 17,000 sales within two weeks is more than respectable.

And all of these Trump books sold as well as they did in part because they were able to promise shocking revelations. Fire and Fury purported to reveal what Trump’s inner circle really thinks of him (supposedly Ivanka made fun of his hair). A Warning was supposed to be the unfiltered truth coming directly from one of those inner circle staff members. Bolton’s The Room Where It Happened contained proof that contradicted Trump’s official story on the Ukraine scandal that led to his impeachment trial earlier this year. And Schmidt’s Donald Trump v. The United States was advertised as the book that would reveal the truth behind what really went down at that impeachment.

The public at first greeted these tell-all books with all the glee of a white-hot media frenzy. But as tell-all followed tell-all, a new question began to emerge.

If Trump was doing so many shocking and arguably illegal things, and the authors of these books knew about them for so long — well, then, why didn’t they tell the public about the president’s misdeeds sooner? Why hadn’t any of these authors made a move before they had the chance to make millions from book sales?

The New Yorker’s review of A Warning opens with a weary citation of all the times Anonymous claims their colleagues “almost made a dramatic stand against Trump, such as in a mass resignation.” Meanwhile, in a CNN op-ed, Rafia Zakaria noted, “While the book takes us on a greatest hits tour of near or actual catastrophes in the Trump White House, the egregiousness of these events seems to have no impact on the author’s evaluation of his or her complicity in them.”

Reporting on the revelations of Schmidt’s Donald Trump v. the United States for Salon, Roger Sollenberger noted pointedly, “It is not immediately entirely clear why these reports, many dating back as far as three years, made it into the pages of Schmidt’s book rather than the subscription-based newspaper that employs him.” (Schmidt is a Pulitzer-winning New York Times reporter.)

And writing for Vox earlier this year, Kreizman described Bolton’s book as one of a rash of exploitative ex-Trump administration tell-alls. “They’re cashing in on their experience in the White House without actually helping the American people,” she wrote, “ignoring official methods of reporting such abuses while they’re currently happening.”

Of all of the shocking Trump exposés I’ve named so far, Fire and Fury was the only one not met with any questions about whether Wolff had an ethical duty to make his revelations public earlier. But there were still ethical questions about the book in plenty, because Fire and Fury does not appear to have been particularly well fact-checked.

In fact, all of these big splashy Trump tell-alls seem to be revealing the same fundamental weaknesses in book-length journalistic reporting. In theory, book-length reporting is supposed to function as the home of the very best of journalism: not as the home for breaking news where time is of the essence, but for the most thoughtful, most rigorous, most carefully sourced reporting in the industry.

But in practice, book-length journalism often fails to perform that duty, perhaps because book publishers generally don’t consider the ethics of journalism to fall within their purview.

Most media companies have an official code of ethics (here’s Vox’s). They may not always follow that code, but they use the structure to guide their general practices, including the publication timelines they develop and the resources they offer employees, including fact-checking.

Book publishers take a more hands-off approach. They usually don’t make it their business to guide their authors’ ethics, and they consider the work of producing a manuscript — including researching and fact-checking — to be strictly the author’s responsibility. The part of the process that book publishers get involved in is screening a manuscript to see if it meets their editorial standards, editing the manuscript to make it read well, producing the manuscript to make the book look good, and marketing the results to make the book sell.

Publishers are involved, in other words, in the part of the process that makes money. The part of making a book that might involve difficult ethical questions is generally something that book publishing leaves its authors to deal with on their own. Which means that when someone like Woodward is working on a report that might have monumental implications for public health, he’s the one who’s expected to spot that issue. Publishers don’t consider such angles to be their business, and generally they don’t have any official public-facing codes of ethics.

Should that practice change?

“Personally, I think it’s a good idea for anyone publishing content meant for public consumption to talk about their ethics,” says the Society for Professional Journalists’ Walsh. “We tell people to be critical news consumers, but then we don’t always provide information to allow them to come to informed conclusions.”

“I come at book publishing from a really idealistic place. I believe in the power of books to change the world and change people’s thinking,” says Kreizman, who used to work in publishing. “I never thought that the book publishing industry would be so embroiled in this ethical monstrosity.”

“I still believe people go into book publishing because they also believe books can change the world, and I think they lose sight of that,” Kreizman adds. “I understand corporate pressures; I understand the need to make money. But I think the truth trumps everything in the age of Trump.”

Woodward has said he came to the conclusion that Trump’s privately discussed information on the coronavirus was correct in May. On May 28, the confirmed Covid-19 death toll in the US passed 100,000. As of September 15, the CDC estimates that the Covid-19 death toll in the US has surpassed 180,000.

It is impossible to say that any of the information contained in Rage could have saved any one of the more than 79,000 American lives that were lost between May and September. But it is remarkable that at no point does anyone involved in the publication of Rage seem to have asked whether there was a chance it could have.

Help keep Vox free for all

Millions turn to Vox each month to understand what’s happening in the news, from the coronavirus crisis to a racial reckoning to what is, quite possibly, the most consequential presidential election of our lifetimes. Our mission has never been more vital than it is in this moment: to empower you through understanding. But our distinctive brand of explanatory journalism takes resources. Even when the economy and the news advertising market recovers, your support will be a critical part of sustaining our resource-intensive work. If you have already contributed, thank you. If you haven’t, please consider helping everyone make sense of an increasingly chaotic world: Contribute today from as little as $3.

Author: Constance Grady

Read More