And it just might be the best artistic rumination on #MeToo and an age of terrible men yet.

BoJack Horseman is not a good person.

That seems self-evident. Over the course of his show’s first four seasons, he’s nearly slept with teenagers. He’s been privy to the overdose and death of a young woman who looked up to him. He’s drank and caroused and just generally burned his life down, over and over again. But he’s rich and powerful. He has money. He has fame. He has excuses, like the undiagnosed depression, or the chemical dependencies, or the shitty childhood.

But he still does bad things. And yet he is not a bad person, necessarily.

He does care for people, and he occasionally thinks beyond himself to care about them on a non-superficial level. He’s helped out many friends, and in the show’s fourth season, he was a surprisingly stable rock for the woman eventually revealed to be his half-sister, who found herself trying to track down her roots (she was given up for adoption) and instead found… BoJack.

The gap between BoJack as he wants to be seen and BoJack as he actually is has always driven BoJack Horseman. It’s one of the reasons I suggested, back in the show’s second season, that it would be a successor to Mad Men, and I’m astonished at how the series hasn’t really gone wrong since. It just might be the single best TV show in production right now, with great laughs but also rich, thoughtful character depth.

And in season five, BoJack Horseman brings all of that character development down around its ears, in a stretch of episodes that represents the most precise dissection of BoJack Horseman yet — and perhaps the first truly sustained artistic response to the #MeToo movement, albeit one that was largely crafted before the fall of Harvey Weinstein (though Mel Gibson was on the show’s writers’ mind).

Look out, folks. Major, major spoilers for season five follow. If you haven’t seen it, look away!

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/8635113/spoilers_below.png)

In its fifth season, BoJack Horseman complicates our ideas about terrible men

If you’ve seen the entire fifth season of BoJack, then you’ll perhaps recognize that my attempt to frame him as neither a good nor a bad person is deliberate. That is, after all how Diane — perhaps BoJack’s truest friend in the whole world — explains her friend to himself when, in a fit of self-loathing, he asks her to essentially destroy his career by writing the sort of exposé of his terrible deeds that has taken down so many other Hollywood bigwigs, in our reality and his.

But Diane refuses to do that, telling BoJack that he’s not a good person or a bad person — he’s just a person. (Or, rather, a horseman, but you get the point.) Yes, he’s done all of those terrible things, and yes, his career might end because of them. But she’s not going to be the one to set that outcome in motion, because it would, on some level, be doing him a favor. It would be indulging one of his self-destructive impulses, and she’s not going to let him commit career suicide by journalist.

As I watched this sequence unfold, I wondered if I would end up feeling like it was a cop-out, if I would grumble to myself at how creator Raphael Bob-Waksberg and his writers had tiptoed up to the precipice of holding their main character accountable in a forum larger than his own mind, then tiptoed right back. In the season’s last section, BoJack checks into rehab to work to contain his latest addiction (to painkillers). The show he was on gets canceled. The reset button is hit.

But the more I think about this sequence and the many leading up to it in season five, the more I think Bob-Waksberg and company haven’t avoided holding their protagonist accountable. After all, if any showbiz satire on television could plumb the depths of its main character being held accountable for past misdeeds by a #MeToo-esque movement, it’s BoJack Horseman, which is as haunted by the past as any great ghost story.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/13089331/BoJack_Horseman_S05E01_21m31s30960f.jpg) Netflix

NetflixIt’s easy enough to imagine BoJack’s ghosts stepping into the light. It’s easy enough to imagine the rest of the series taking place in a world where BoJack keeps fighting to get his career back, only to realize that the meaning of words like “redemption” and “forgiveness” has to be more than skin deep. And it’s easy enough to imagine these writers finding a way to make that battle resonate with our current era.

But that is also, on some level, too easy an answer for this show. BoJack wants Diane to write an article taking him down, because he wants to punish himself. He doesn’t believe he’s worthy of love or admiration or anything good, because he’s done monstrous things. He wants someone to slot him into the role of villain, because he knows that he has acted like a villain and might still do so again. And once he’s accomplished that, he can finally drift away, secure in having isolated everyone he cared about.

BoJack Horseman has always been about how our worst impulses feed into each other, all of the ways that mental illness can feed addiction, or that addiction can feed doing terrible things to other people. (BoJack physically assaults his female co-star and lover this season, in an on-set stunt that goes horribly wrong partly because he’s so high.) And the show concentrates on this theme not to excuse bad behavior, but, instead, to try to help us understand how it can be better combatted before it happens, how self-loathing becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy of destruction — I am a shitty person, who does shitty things. Well, what if you’re not?

Yes, there are monsters in the world. But there are also so many people like BoJack, who have done monstrous things — perhaps many monstrous things — but who are not beyond redemption, who might yet be forgiven. What does that look like? And how do we find our way there? Answering those questions is the work of the rest of this remarkable series, I suspect, but it’s also ground zero for season five.

Season 5 interrogates a culture that celebrates those who refuse to take responsibility for themselves

The role BoJack plays in season five is that of a disturbed and distressed detective named Philbert, in a series named Philbert (just as BoJack Horseman is named for BoJack Horseman). Run by the self-proclaimed genius Flip McVicker (a very funny Rami Malek), the in-show series allows BoJack to lampoon just about every trend of dark cable and streaming dramas, which leads to some of the season’s best jokes.

But it also adds a surprisingly important thematic underpinning to the entire season, as these sorts of dark dramas are often about those who seek to skirt responsibility for terrible things they’ve done. When Philbert suspects that he might be the one who killed his wife (the crime that haunts him), his show lets him off the hook by inventing a twist that proves he didn’t do it. It’s indicative of a culture addicted to pretending responsibility is a joke, that if you really try hard enough, you can absolve yourself of bad deeds without having to work at redemption.

These ideas course through the season, with each and every character longing to avoid responsibility for something they’ve done — be it playing a part in a crumbling marriage, not breaking up with someone who’s not going to be a good long-term partner, or the darker deeds of BoJack.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/13089333/BoJack_Horseman_S05E02_23m27s33736f.jpg) Netflix

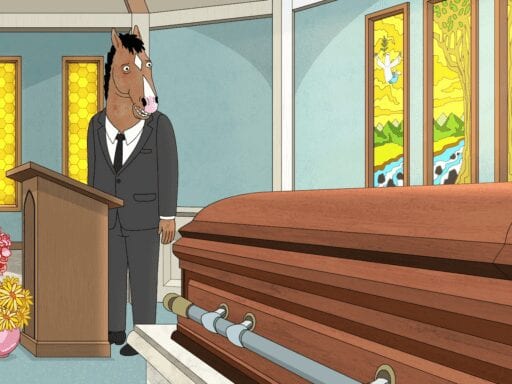

NetflixBut the series also twins that idea with the idea of blame, the idea of finding a scapegoat and sometimes even a completely justifiable scapegoat. The most daring episode of the season is its sixth, which consists entirely of a single long monologue delivered by BoJack, a eulogy for his recently deceased mother. (If Will Arnett doesn’t win an Emmy for his voice performance, it will be a bigger travesty than usual.) It’s a full episode’s worth of grappling with what it means to be someone’s child and maybe someone’s parent, with how hard it can be to have traumas you weren’t privy to visited upon you by a parent, with the challenge of accepting that you might have inherited their damage, might literally be carrying their time bomb in your genes.

But even as the series insists we can inherit damage, can have trauma visited upon us, it doesn’t let those who pass along that trauma to others get off easily. If there is a reason BoJack can remain our protagonist, it’s because he, however fitfully, makes a few steps forward every season. Season five might feature his blackest pit yet, but it also features genuine moments of kindness between him and his friends, and what might amount to his most successful relationship yet on the show — before he destroys it with his actions, that is.

I realize this makes the series sound a little like Philbert, at least in the sense that it’s a self-important slog. And the construction of season five might be a little less cohesive than the show’s gorgeous, devastating season four. (I will have to watch it six more times to be sure.) But the series remains as winning and funny as ever alongside all of this, and possessed of a confidence in its ability to do whatever it likes — including staging an episode where two characters who seemingly have nothing to do with the main plot fill us in on the other characters’ adventures anyway. There’s also side story involving a mad sex robot who ends up running the series’ version of Netflix. What’s not to love?

And yet it doesn’t matter if season five is BoJack’s best season yet or not quite as good as last season or [insert your ranking here]. It feels ever more like a miracle that this show exists and that it refuses to give lazy answers to complicated questions. There is no show as effective at plowing this particular ground and at finding answers that are at once satisfying and elusive. It is a beautiful show, and one that constantly finds new ways to surprise me.

Long may it run.

BoJack Horseman’s five seasons are all available on Netflix. Did I forget to mention that BoJack is a literal horse man, and the show takes place in a world full of bipedal animals who live alongside humans? Well, it does, but you probably knew that already.

Author: Todd VanDerWerff