Why Ortega’s latest move to open up society doesn’t mean the country’s press is free.

Most repressive countries interested in censoring information and the media try to lock down the internet, but for the past two years, Nicaragua has had an old-school solution: just remove the tools of the trade.

Police have seized a TV station’s broadcast facility, government supporters have burned down radio stations, and for nearly the last year and a half, customs officials have blockaded shipments of newsprint and ink for print newspapers. This month, that last restriction, at least, was finally lifted.

President Daniel Ortega’s administration released the impounded materials two weeks ago, loosening its grip on the independent press just enough so that the country’s paper of record, La Prensa, can avoid shutting down. The country’s other dailies haven’t been so lucky.

Since August 2018, La Prensa’s daily print edition has slowly shrunk from 32 pages to eight, before they finally had to switch to printing the shorter issue on regular, locally available — and more expensive — paper.

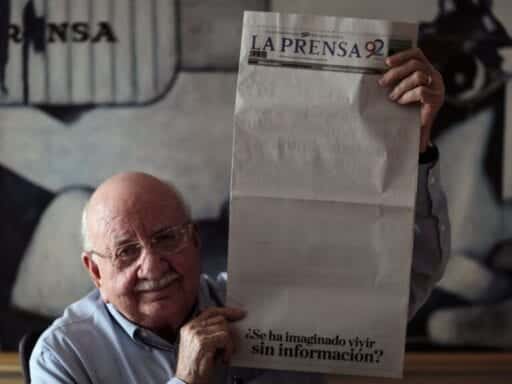

“The blockage on the press and on press freedom has been opened,” La Prensa director Jaime Chamorro said two weeks ago at a press conference as the materials arrived. “I think this is a good sign, not just for other media outlets that have been closed but also for the opening up of Nicaragua.”

The paper, which has been the daily staple of Nicaraguan news since its founding in the 1920s, received no explanation for why the materials were being released now, Chamorro said. The Nicaraguan customs office declined to comment.

“I think it benefitted [the government] too, not just us,” Chamorro said after suggesting the paper’s pressure campaign might have finally helped end the blockade. “Because imagine it, if La Prensa had been closed down, we would have been the first country in the world without a print newspaper.”

It’s another sign that Ortega’s administration is trying to quietly restore normalcy to the country after nearly two years of heightened repression — without admitting any wrongdoing. After winning reelection in 2006, Ortega implemented several social programs, such as his “Zero Hunger” initiative, that benefited many. But he and his now vice president-cum-first lady Rosario Murillo have also consolidated power over the courts and Supreme Electoral Council, removed constitutional term limits, and restricted the independent media’s access to official government sources.

That all came to a head in April of 2018, when state security forces’ violent suppression of protests transformed a narrow complaint about proposed social security reforms into a broad anti-government movement. The months of ensuing civil uprising — and the government’s response — culminated with over 300 dead, a hamstrung economy, and a country deeply divided over issues of free speech and government abuses.

Today, Nicaragua is aggressively trying to project an air of normalcy, courting the tourists who fled. And, to an extent, the country has succeeded. 2018’s ubiquitous protest graffiti is white-washed over; 20-somethings shout to be heard in packed nightclubs that were barricaded shut during the crisis; and some well-known political activists are even returning from self-imposed exile.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19709723/1199282369.jpg.jpg) Inti Ocon/AFP via Getty Images

Inti Ocon/AFP via Getty ImagesThis month’s decision, brokered by the Vatican’s top diplomat in Nicaragua, comes just weeks after the storied outlet published an editorial hinting it might have to close.

The once-national paper had to cut staff and limit distribution to just the capital of Managua and one or two other provinces, said Eduardo Enríquez, La Prensa’s long-time managing editor.

“We were a hundred journalists before April [when the crisis began], and now we’re less than 30; the business has been hit hard,” he said at the press conference this month.

La Prensa’s staff had continued publishing online for their 2 million unique monthly visitors, distributing on WhatsApp, and producing other multimedia content. In fact, the digital team won the Inter-American Press Association’s Excellence in Journalism award for its coverage of the 2018 crisis. But for many readers, it’s newsprint or nothing.

“[T]here is a big part of the population that likes to read the paper every morning,” Enríquez told Vox last fall. “Some people, if we don’t put it in the paper, they feel like we haven’t talked about it or published anything about it.”

La Prensa, owned by members of the same Chamorro family that has included leaders of opposition political parties, is a vocal critic of Ortega. Its editorial line for years was to call him the “unconstitutional president,” starting when he ran for a then-unconstitutional third term in 2011. Thankfully, Enríquez said, its journalists weren’t individually targeted during the crisis as some journalists were.

President Donald Trump’s administration, which has kept up pressure on Managua as part of a broader effort to target socialist Latin American countries, celebrated the release of the newsprint. Michael Kozak, the State Department’s acting assistant secretary for the Western Hemisphere, tweeted his support — and a call for the return of “property confiscated from other independent outlets.”

The long-overdue decision to release @laprensa’s paper & ink from Nicaraguan customs is a step in the right direction.

Now Ortega should return property confiscated from other independent outlets like @confidencial_ni and @100noticiasni. Freedom of expression is a #HumanRight.

— Michael G. Kozak (@WHAAsstSecty) February 7, 2020

Nicaragua’s stance toward the independent press is still adversarial, however, and Murillo —as chief of communications — keeps a tight grip on government information.

“Nothing happens here without Ortego or Rosario authorizing it,” Enríquez told Vox. “Their supporters say, ‘If the comandante knew about this,’ but he knows, and she knows.”

The last two years have been rough for Nicaraguan journalists

It’s not only La Prensa that nearly stopped printing, or the other two daily papers who were run out of the print business; a wave of independent and opposition outlets have been forced to close their doors in Nicaragua.

The environment for journalists took a nosedive as the country’s civil crisis broke out in April 2018. According to an annual global report by Article 19, Nicaragua had one of the largest drops in press freedom from 2017 to ’18.

Some outlets the administration didn’t need to target. They were the victims of the generalized anti-media climate the administration created. Taking a page out of the book used by Trump and authoritarians everywhere, state journalists and officials regularly called critical journalists and reporters covering protests “traitors” and “golpistas” (coup-plotters).

Henry Blanco, a 30-year-old street reporter for Radio Darío, an independent station in the city of León, told Vox last year that “you could never practice journalism completely freely … but everything became more complicated in April 2018.”

As protests broke out that month, Blanco witnessed state repression against both demonstrators and reporters rapidly escalate: “on April 20 … we began seeing videos of journalists being attacked.”

While Blanco sat in Radio Darío’s transmitting booth on the 20th, relaying the breaking news that another station, Tu Nueva Radio Ya, had been burned down by government supporters, the station received an anonymous call promising violence against his team of reporters by sundown.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19731856/950917104.jpg.jpg) Inti Ocon/AFP via Getty Images

Inti Ocon/AFP via Getty ImagesShortly thereafter, another call — this time from a head of the governing party — made the threat even more explicit, telling reporters in the station that, if they did not stop broadcasting about government violence over the air, they would be killed.

At 7:25 pm, as some of Radio Darío’s team sat down to eat a quick working dinner in the office, they heard a gunshot blast open the lock on the station’s front door, then an explosion. “Suddenly,” Blanco said, “the [recording] booth was ablaze.”

Trapped in the burning station, and worried that beyond the front entrance were men armed with guns, Blanco remembers that some of his colleagues were so paralyzed by fear they “couldn’t do anything but cry.”

Blanco and his colleagues narrowly escaped through a backdoor, but no firefighters or police answered their calls. The group of reporters watched their station burn to the ground.

The terrorizing of the press didn’t end when Ortega reconsolidated power that summer.

In December of that year, two independent stations who’d criticized the government and amplified live videos of violence in the streets, Confidencial and 100% Noticias, were raided by the police, who seized equipment and prevented journalists from reentering the premises.

“I wanted to go film it,” Lucía Pineda, news director of the still-shuttered 100% Noticias, told Vox, recalling when she learned the station had been seized. “But police suddenly opened the door to our office and I ran down the stairs and hid under the staircase and there broadcast my final report, that the police had taken control of the station.”

She and the station’s director Miguel Mora were jailed for nearly six months, on charges of “inciting violence and hate” and “promoting terrorism.” They’ve been released, and the station’s journalists continue to broadcast online. But the channel’s offices are still shuttered, under the state’s control.

And even the newly liberated La Prensa says it’s going to have to “study” how and when to reexpand its print edition — though its leaders vowed to continue practicing its critical journalism that speaks truth to power: “La Prensa has been doing that for 93 years, it’s not going to change,” Enríquez said.

But one critical paper does not a robust, independent press make.

“The channel 100% Noticias must be returned to its owners and Confidencial must be allowed to return to their offices” he continued. “Other media outlets are still in trouble, and we, as independent media, still have no access to government information. … All this has to open up before we can even begin to think that there is freedom of the press, freedom of expression and access to information.”

Reporting for this story was supported by the Justice for Journalists Foundation.

Author: Caroline Houck

Read More