Full carbon neutrality is now on the table for the world’s fifth largest economy.

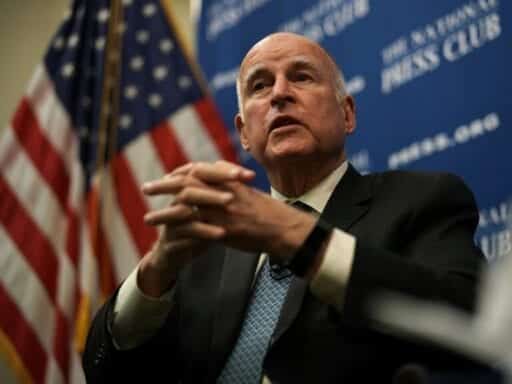

California Gov. Jerry Brown kicked off a week full of climate change news with an announcement, and boy was it a doozy: at once surprising, strange, and stunning. It was so out of left field and yet so profound in its implications that few in the media, or even in California, seem to have fully absorbed it yet.

To explain, we must begin with a little backstory.

This week, from September 12 to 14, the Global Climate Action Summit will take over San Francisco. The big climate shindig — three days of meetings, exhibitions, and glad-handing with big names in climate policy from around the world — will, among other things, serve as a kind of capstone celebration of Brown’s climate legacy.

Brown had hoped to begin the week by signing a high-profile package of energy bills. The one he most wanted to sign, into which he had poured the most political capital, was a bill that would link California’s energy grid to a larger Western power market. The one for which he had shown the least enthusiasm, into which he had put the least capital, was a bill that would commit California to 100 percent use of zero-carbon electricity by 2045.

The latter bill, shepherded by state Sen. Kevin de León, passed the legislature. The former bill did not. Initially there were rumors that Brown was threatening to veto de Leon’s bill if the regionalization bill wasn’t also passed in a special session, but that was probably a bluff, and so on Monday, more or less as expected, Brown signed the bill, SB 100, into law.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/12897447/580951026.jpg.jpg) Jessica Kourkounis/Getty Images

Jessica Kourkounis/Getty ImagesThat is big news in and of itself; 100 percent clean electricity is a difficult and worthy challenge.

But Brown didn’t stop there. Much to everyone’s surprise, on the same day, he also signed an executive order (B-55-18) committing California to total, economy-wide carbon neutrality by 2045.

Wait, whaaat? Zeroing out carbon entirely in California? In just over 20 years? In my expert opinion, that is … holy shit.

Let’s remember that this is only an executive order, not a law, and there are reasons to greet it with some skepticism, or at least hedged expectations. We’ll get to them in a second.

But y’all: If California really did this — if the world’s fifth-largest economy really targeted economy-wide carbon neutrality by 2045 — it would be the most significant carbon policy commitment ever. Anywhere. Period. It would yank the Overton window open, radically expanding the space of climate policy possibilities.

Economy-wide carbon neutrality, explained

The key to understanding the significance of the goal is grokking the difference between “electricity” and “energy,” which has continually been blurred by the mainstream press (and by some enthusiastic environmentalists).

SB 100, the bill Brown signed on Monday, commits the state to clean electricity by 2045, but electricity only accounts for about 16 percent of California’s greenhouse gas emissions. Brown’s executive order would commit the state to doing something about the other 84 percent — transportation, building heating and cooling, industry, all the many and varied energy services that rely on direct fossil fuel combustion rather than electricity.

This is the holy grail of climate policy: a large, modern economy getting to zero net carbon. It came into view faster than I ever would have predicted 10 years ago. Or five years ago. Or, uh, 24 hours ago!

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/6373271/holy-grail.jpg) Shutterstock

ShutterstockGiven its significance, Brown’s order justly could have served as a culminating announcement at the end of the big climate week, a kind of policy finale. It could have been a very big deal.

Instead, no one that I’ve talked to had any idea it was coming. It dropped without advance notice, alongside another major climate announcement (SB 100), muddling and muting the media coverage. As a rollout strategy, it was some mix of incompetent and malicious.

“I see this as an effort to grab the political spotlight away from Kevin de León more than a serious stab at policy,” said R.L. Miller, head of the climate lobbying group Climate Hawks Vote. If it was that, it certainly failed — SB 100 dominated most stories. Perhaps Brown will reannounce his order later this week, for real this time.

Even if Brown’s gambit is taken on good faith, though, there are reasons not to get carried away about it.

Executive orders are not durable or binding on their own

Brown could order the state to run on unicorn farts if he wanted to — he’s the executive, he gets to issue orders to executive agencies — but he cannot make it happen on his own. State agencies can research, develop road maps, and recommend policy, but to make it real, the legislature will have to pass a law (or, more likely, laws), and that will occasion a long and bloody political battle. For the state’s fossil fuel industries, that battle would be existential.

And it would be easy enough for a subsequent governor or legislature to overturn the executive order. Until it is backed up by tangible political organizing and advocacy, it will remain aspirational. It is not law; it is but a guidance, a lighthouse to which policy must eventually navigate.

Politically, the order is Brown’s way to put on record some of the grander goals that the legislature fell short of this session — laying a marker for policymakers to return to in the future and putting some old enemies on notice. For instance, carbon neutrality will require a great deal of the oil industry, which fought Brown tooth and nail for years, and of the NIMBYs that helped defeat SB 827, the urban density bill. It will also probably require grid regionalization.

The slapdash way the executive order was introduced doesn’t exactly bode well for how seriously it will be taken, beyond its political symbolism. But before skepticism carries us away, let’s recall California’s history.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/3763668/schwarzenegger-lcfs.0.jpg) Justin Sullivan/Getty Images

Justin Sullivan/Getty ImagesBut executive orders are often the trigger for California climate progress

California’s climate and energy policies have been getting steadily more stringent for years, ratcheting up through a predictable and transparent process.

That process often begins with an executive order, as it did in 2005, when Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger issued an order establishing carbon-reduction targets through 2050. Like Brown’s order, it had no force of law, but it served as a rallying point for organizers. The following year, the legislature passed a version of it as AB 32, the Global Warming Solutions Act of 2006, which established the machinery of emission reductions that operates in the state to this day, including an empowered Air Resources Board (CARB) and a cap-and-trade system.

That machinery has been strengthened over time (though CARB’s independent authority took a bit of a hit with last year’s climate bill). Now, via SB 100, it is being deployed toward the target of zero-carbon electricity.

Brown’s order is meant to get the next phase of that process, which involves moving beyond electricity to other sectors of the economy, underway. Of course, he can’t do it by himself, but he can point future policymakers in the right direction — and lock his gubernatorial successor into the same goal.

The executive order makes the fight for the next legislation easier; legislation makes the next order easier. It’s all part of California’s virtuous cycle of climate policymaking.

Carbon neutrality is a mind-boggling goal

The implications of California targeting carbon neutrality are massive, well beyond the scope of a single post. Only Hawaii shares that goal, and Hawaii is … Hawaii. California’s economy is bigger than that of the majority of the world’s nations.

Adopting this target in earnest would put California firmly in the lead position on climate policy, not just in the US but globally.

As I’ve argued before, “zero” is much more powerful than nerdier climate targets like 2 degrees Celsius or 350 parts per million of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. “Zero” is clear and intuitive.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/5841489/riding-zero.png) Shutterstock

ShutterstockAnd it’s one thing to target zero in electricity, but to target net-zero carbon emissions, period, across the entire economy, is a whole other thing. That means everybody, in every single industry, knows that they too are going to have to get rid of carbon. They too are involved in this undertaking. Everybody is involved. We’re doing this thing.

And it’s real easy to know if you’ve succeeded. Are you putting more greenhouse gases in the atmosphere than you’re taking out? Then you’re not done.

Economy-wide zero is a clear, intuitive, and inspirational target that would move decarbonization out of “energy policy” and into the center of the state’s very identity. It would spark an immediate explosion of innovation in sectors that don’t get enough attention in climate policy, like buildings, industry, and freight. It would spur new technologies like hydrogen fuels made from sunlight and virtual power plants. And it would immeasurably strengthen the hand of every urban policymaker pushing for greater density and multimodal transportation.

It would also put enormous new responsibility on the shoulders of the state’s cap-and-trade system, which already has problems and growing pains. Expanding that system to cover the entire economy would be some seriously Star Trek policy, boldly going where no one has gone before.

Finally, suffice to say, economy-wide aspirations would also mean an economy-wide political fight, involving oil, gas, coal, refineries, ports, trucking companies, the auto industry, the whole sprawl industry, agriculture, a bunch of industries I’m probably forgetting, and the financial resources of every wealthy conservative donor with a stake in fossil fuels, which I’m told is quite a few.

It will be a battle royal, a political and economic revolution that will make the fight for clean electricity look like tiddlywinks. And there’s scarcely any way to know how it will play out. But with his executive order, Brown has fired the starting gun.

“Carbon neutrality” will only be as strong as policymakers make it

Notice that I’ve been saying net zero carbon rather than simply zero carbon. There’s a reason for that: The target is not to eliminate all carbon emissions, but to eliminate as many as possible and balance the rest with “negative emissions” — i.e., removing CO2 from the atmosphere. As long as the amount you’re taking out is equal to the amount you’re putting in, you’re carbon-neutral.

But what exactly counts as taking carbon out of the atmosphere? There is a lot of room for interpretation there, for policy loopholes and accounting shenanigans.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/12901251/carbon_engineering.jpg) Carbon Engineering

Carbon EngineeringOne way to sequester carbon is to capture it from power plant or factory smokestacks and bury it underground. That’s straightforward enough, and easy to measure, but it’s also expensive as hell, and unlikely to be responsible for any substantial “negative carbon” by 2045.

Carbon can also be sequestered by preserving or growing forests, but that gets extremely difficult to measure. And California could buy carbon credits, which would theoretically represent carbon reductions by entities out of state, but those are even more controversial, with even more room for accounting tricks.

Carbon dioxide can be distilled into a pure form and sold (for instance, by this fancy new natural gas power plant), either to boost oil recovery or to be incorporated in other products. But then how much of that CO2 ends up getting released into the atmosphere later? Measuring those carbon flows, economy-wide, will be an enormous administrative challenge.

The point is, “carbon neutrality” leaves quite a bit of wiggle room. It would be entirely possible for future California policymakers to settle for a weak version of it, one that allows substantial carbon emissions within the state to continue (usually polluting vulnerable communities) as long as they are “offset” by carbon credits and other cheap gimmicks. A weak-enough version would basically be tantamount to the state’s existing carbon target of 80 percent reductions by 2050 — it would just require “offsetting” the other 20 percent.

But that’s a fight climate hawks would eventually face regardless; there will always be pressure to take the easier route. It will be a lot easier to fight that fight with the EO in place than it would be without it. Brown cannot control or constrain future policymakers, but he can fortify future policy advocates and entrepreneurs.

Whatever its internal tensions, California’s climate policy apparatus is working

Brown and de León have a complicated relationship, which perhaps explains the peculiar way the executive order was introduced. But whatever their occasional rivalries or disagreements, from an outside perspective, they are serving as an effective tag-team duo.

SB 100 is a powerful law, a political and coalition-building victory as well as a policy achievement, and de León deserves enormous credit for it. Brown’s order is a signpost and an inspiration, a clear vision of where the state needs to go. Together, they ensure that California continues to accelerate and keeps its eyes on the horizon.

For the first time, true carbon zero is on the table as a policy option in the US. We might actually see it happen in California, in our lifetimes. It’s a stunner, a ray of hope in otherwise dark times, and a fitting way for Brown to conclude his long and fertile career of public service.

Author: David Roberts