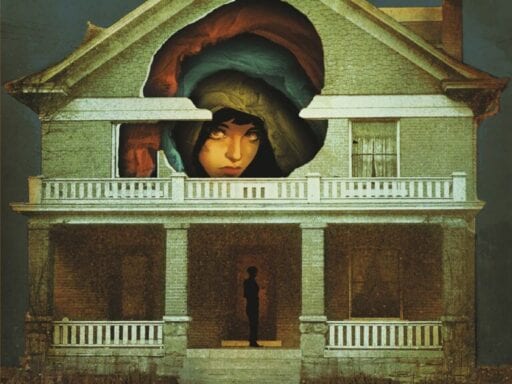

In the Dream House grapples with finding ways to talk about an abusive relationship between two women.

Carmen Maria Machado’s In the Dream House is a memoir told in fragments, in shards. It has to be, because it is a memoir of trauma, and memories of trauma are fragmented.

Specifically, In the Dream House is a memoir of Machado’s abusive relationship with an ex-girlfriend. Over the course of the memoir, Machado meets her girlfriend — referred to only as “the woman in the Dream House” — and finds herself rapidly infatuated, wooed, love bombed. And then, eventually, the abuse starts.

The woman in the Dream House accuses Machado of infidelity, of flakiness, of being inconsiderate. She screams in her ears. She ambushes her in the shower. She chases her from room to room and then, when Machado finally emerges, asks sweetly, “Why are you crying?”

As Machado retells the story of their relationship, she spends each brief chapter playing with a different narrative trope: noir, erotica, folklore taxonomy. In many ways, this format is an echo of Machado’s much-celebrated debut, Her Body and Other Parties. That book was an anthology, a collection of short stories that skipped playfully between genres but revolved around a single theme: women, their bodies, and other parties who believe themselves to be entitled to those bodies.

In the Dream House skips between genres less playfully, but revolves around a variation on the same theme: Machado herself, her body — as well as her mind and emotions, with the titular “dream house” acting as a metaphor for Machado’s body — and the woman in that dream house, who believes herself to be entitled to control over Machado.

But while Machado is fluent in many genres, her native tongue is the fairy tale, and specifically the dark and bloody Angela Carter kind. So throughout In the Dream House, no matter what narrative trope or genre is framing the chapter at hand, she uses footnotes to mark off fairy tale motifs as they occur. A post-coital daze is marked, “Weakness from seeing woman (fairy) naked.” When after their breakup Machado has trouble getting herself off, she duly footnotes the text, “Magic power lost by breaking taboo.”

Fairy tales are in many ways about the making and breaking of taboos — leave the ball before midnight, don’t steal from the witch’s garden, don’t neglect to invite certain fairies to your child’s christening — and their stringent yet arbitrary lists of rules make them a perfect metaphor for talking through an abusive relationship.

There is no reason that if Cinderella stays at the ball past midnight, her magic gown and carriage and glass shippers should disappear. It just happens, and it feels inevitable. There is no reason that Machado’s refusal to let the woman in the Dream House drive a car when she’s drunk should result in the woman screaming “I hate you, I’ve always hated you” at her, while transforming into “this fuzzy pale mass” with “her mouth a red hole.” It just happens, and in the moment, it feels inevitable. It’s only in hindsight that Machado is able to see how toxic and damaging that moment truly was.

Part of what makes Machado’s relationship with the woman in the Dream House so poisonous is that since they are both women, it does not align neatly with our culture’s ideas about abusive relationships. Machado doesn’t have a vocabulary for talking about what is happening to her — in the same way, she writes, that she didn’t have a vocabulary to figure out what was happening when she was in the 10th grade and developed her first crush on a girl. “Our culture does not have an investment in helping queer folks understand what their experiences mean,” she concludes.

She has to research to find other stories like hers — but once she starts looking, they are everywhere, story after story about the abuse of queer women by other women. “There is a pie chart that encompasses those years of my life,” she writes, with palpable disbelief. “A pie chart!” In the end, she finds, the story of her abuse is “common, common as dirt.”

But Machado’s telling of this particular story is anything but common: It’s compassionate and thoughtful and achingly honest. Most of all, In the Dream House is a generous book. It is generous to all the readers of the future who might find themselves in the Dream House as Machado did. And so that they don’t have to make up their own language to make sense of what is happening to them, it offers itself up, bare and vulnerable.

Author: Constance Grady

Read More