China just stepped up its climate goals. Is it enough to avert climate chaos?

Imagine China — the world’s top emitter of carbon, which in 2019 released nearly double the emissions of the US — with almost zero coal power plants.

Imagine it with zero gasoline-powered cars, and with more than four times the 1,200 gigawatts of solar and wind power capacity installed across the world today.

This could become reality by mid-century if China follows through on President Xi Jinping’s latest commitment to addressing the climate emergency.

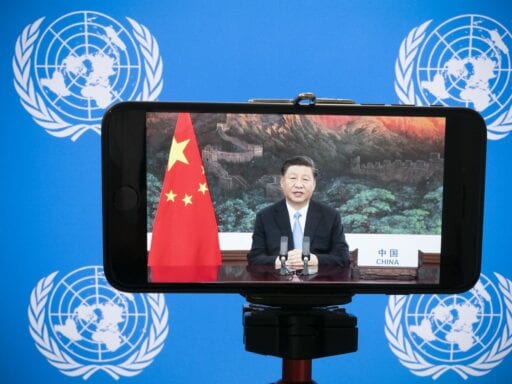

At the United Nations General Assembly on September 22, Xi Jinping announced that China will strive to be “carbon neutral” by 2060. “Humankind can no longer afford to ignore the repeated warnings of Nature and go down the beaten path of extracting resources without investing in conservation,” Xi said.

Going carbon neutral means that China would remove the same amount of carbon it’s emitting into the atmosphere to achieve net-zero carbon emissions. So, by 2060, China would theoretically only use clean energy sources and capture or offset any remaining emissions. But Chinese officials have yet to define exactly what that would look like.

Still, the target puts China more closely in alignment with the European Union, the UK, and other countries that have committed to carbon neutrality by 2050, which the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change said is required to prevent over 1.5 degrees Celsius of warming. In the US, some states and cities have moved in this direction, too. For instance, former governor Jerry Brown signed an executive order in 2018 for California to be carbon neutral by 2045. And Michigan’s governor made the same commitment Wednesday.

Along with the pledge to be carbon neutral by 2060, Xi Jinping also announced that China would submit a stronger set of goals under the Paris agreement and that China would aim to peak carbon emissions before 2030, upping the commitment from “around” 2030.

Meanwhile, in his UNGA remarks, President Trump defended his decision to withdraw the US from the “one-sided” Paris agreement while criticizing China for “rampant pollution.”

Increasingly, China is demonstrating it will use climate as a way to upstage the US, with Xi repeatedly committing to incremental climate action on the international stage in recent years.

Xi Jinping’s climate pledge at the UNGA, minutes after Trump’s speech, is clearly a bold and well calculated move. It demonstrates Xi’s consistent interest in leveraging the climate agenda for geopolitical purposes.

— Li Shuo_Greenpeace (@LiShuo_GP) September 22, 2020

And the latest climate announcements are also in keeping with China’s more assertive role in global governance under Xi’s rule — the country has become more active in international institutions long dominated by Western countries and created its own, such as the Asian Infrastructure and Investment Bank.

Xi’s 2060 pledge “reflects China’s resolution to take international responsibility for addressing climate change,” said Li Zheng, executive vice president of Tsinghua University’s Institute of Climate Change and Sustainable Development.

Besides the geopolitical motivations, China also has a lot to lose from unmitigated climate change, from catastrophic floods like those this summer in the central Yangtze River Basin to worsening heat waves and sea-level rise, which will have a huge impact on coastal cities like Shanghai by 2050.

But transforming such a carbon-intensive economy in the next 40 years is a gargantuan task. “China is still in the process of developing its economy, energy consumption will continue to rise, and China’s energy consumption relies heavily on coal. Achieving carbon neutrality under these circumstances is very difficult,” said Li Zheng.

China has yet to publish an official plan for how it would achieve carbon neutrality, but climate researchers have mapped out pathways. The good news: Researchers say it is possible. Some of the key shifts are already underway — toward electric vehicles and renewable energy, for example. But China will be entering uncharted territory when it comes to cleaning up its behemoth steel and cement industries.

Let’s break down the biggest steps China will have to take to get to a carbon neutral 2060 and assess whether it is currently heading in the right direction.

What it will take for China to get to net-zero carbon

The Energy Transitions Commission — a global coalition of energy experts and industry members committed to achieving the Paris Agreement targets — published a report in collaboration with the Rocky Mountain Institute last year modeling how China could get to net-zero carbon emissions by 2050.

They found that “it is technically and economically possible for China to achieve net-zero emissions by 2050 at a very small economic cost to growth and consumer living standards, and China is well placed to gain technological competitive advantage from the transition to net-zero emissions.”

This rosy assessment might leave you wondering why China didn’t embrace carbon neutrality sooner. Some real concerns include the massive social transition as Rust Belt regions move away from coal and steel, the implications for international competitiveness if other countries don’t decarbonize at the same pace, and how the local and national governments will pay for new infrastructure.

The study’s scenario doesn’t get into all of these details, and it is just one possible route, but it shows the magnitude of changes that China will have to make in the coming years and the challenges involved.

Let’s start with the power sector. In keeping with the expert consensus on decarbonization, the crux of China’s odyssey is electrifying its economy as much as possible, from switching to electric vehicles to using electricity instead of coal for some industrial production. To get to carbon neutral, China’s current electricity generation will have to more than double to 15,000 terawatt-hours by 2050, RMI projects (all figures in this section are from the report unless otherwise noted).

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/21911656/Screen_Shot_2020_09_25_at_12.20.11_PM.png) Rocky Mountain Insitute

Rocky Mountain InsituteIn 2019, almost 70 percent of China’s electricity generation came from thermal sources (90 percent of which is coal power). In the RMI scenario, by 2050 that will drop to just 7 percent, which will be natural gas coupled with carbon capture technology.

To replace fossil fuels, China will make wind and solar the center of its power grid — combined they will supply 70 percent of electricity. China already leads the world in wind and solar, but capacity would have to increase nearly 15 fold, and investment would have to double for solar and triple or quadruple for wind.

“The difficulty of decarbonizing the power sector is improving the flexibility of the system,” said Chen Ji, a principal at the Rocky Mountain Institute in Beijing who co-authored the report. To back up this renewable energy grid when the sun isn’t shining and the wind isn’t blowing, the country would rely on a vast system of batteries and pumped-hydro storage, as well as the remaining thermal capacity, expanded nuclear power, hydropower, and biomass, according to the scenario.

Decarbonizing the power grid is just the first step. The country’s main consumers of fossil fuel — transportation, buildings, and industry — would also have to be fully transformed, tapping into the new, clean grid. For example, in the scenario, all passenger vehicles and all trains would run on electricity. China already has the world’s largest high-speed rail network (which uses electricity); under the scenario, it will increase by 50 percent to 45,000 kilometers of track. China is also the world leader in electric vehicle production, but electric cars only made up 2.5 percent of total sales in 2018 so production will have to scale up dramatically.

These changes are monumental alone, but the greatest challenge is decarbonizing heavy-duty transportation and heavy industry, according to Chen. Aviation, shipping, and trucking are very hard to electrify in part because most electric vehicle batteries are currently not designed to supply power over such long distances.

Similarly, it is hard to electrify industrial production, as Vox’s David Roberts explained earlier this year. To reach the high temperatures required to produce steel and cement, coke — processed high-grade coal — is typically used. Steel production alone is responsible for 15 percent of China’s carbon dioxide emissions, so finding alternatives to coal is critical.

But there is another solution for these sectors: hydrogen.

“Electrification plus a hydrogen economy will be the technological solution for the energy transition for zero carbon China,” said Chen. Hydrogen is a leading contender to replace coke for steel and other industrial production, but it is not cheap, and green hydrogen production is even more expensive, as Roberts explained.

To make steel in 2050, the RMI scenario proposes a combination of recycling steel and using hydrogen or coal with carbon capture to produce new steel (the model calls for a 50/50 split between the two methods).

The problem is, China is just beginning to explore the use of hydrogen for steel and cement. China has to “start from scratch,” according to Chen. There is strong interest in hydrogen, but it is coming from coal companies that want to use their coal to produce hydrogen rather than using renewables to produce the “green hydrogen” needed, he explained.

“In these ‘harder-to-abate’ sectors, hydrogen is a solution, but there are still major challenges to make hydrogen production green,” Chen said.

It is dizzying to consider the scale of change required to jumpstart the hydrogen industry to supply China’s industrial giants and long-haul trucks — and this is just a snapshot of the full transition that getting to net-zero carbon will require.

And even though the scenario may be technically and economically feasible, the seismic shifts in Chinese society also have to be taken into account. For instance, millions of workers in the coal and steel industries would have to transition to new roles. Chen said “the transition is very, very difficult,” adding that local governments in coal-rich provinces have been focused on this issue for a while.

While tackling carbon emissions alone is a herculean task, Xi’s 2060 goal does not mention non-CO2 greenhouse gases, which accounted for 16 percent of total greenhouse gas emissions in 2014 and also need to be addressed.

Is China on track to reach net-zero carbon by 2060?

How China intends to achieve carbon neutrality will be fleshed out once it lays out an official roadmap, but the immediate need is clear: setting short-term climate goals that align with this new long-term vision.

The news over the last few months has provided cause for concern and hope about China’s emissions trajectory in the coming years. Even as Xi Jinping announced the 2060 target and called on countries to “achieve a green recovery of the world economy in the post-Covid era,” China’s emissions over the summer jumped compared to last year, driven by Covid-19 stimulus investment in carbon-intensive infrastructure projects, and an analysis published in Carbon Brief found that key provinces are pouring more investment into fossil fuel projects compared to low-carbon energy projects. Meanwhile, China also raised its renewable energy targets in June after exceeding them, but provinces have approved new coal power projects at their fastest clip since 2015.

In his UNGA speech, Xi Jinping did also commit to stronger short-term action, saying China would enhance its targets under the Paris Agreement and strive to peak emissions before 2030, rather than “around 2030,” the country’s initial commitment. (China’s carbon emissions grew 2 percent last year.)

Todd Stern, Obama’s lead climate negotiator, said on Twitter that a stronger commitment was needed:

President Xi’s statement that China aims to hit net zero carbon before 2060 is big news – the closer to 2050 the better. But peak emissions before 2030 not good enough and new coal plants not good at all. This decade crucial for net zero 2050-60. Great step; actions must follow.

— Todd Stern (@tsterndc) September 23, 2020

The next few months will reveal how serious China is about accelerating its decarbonization. Countries were expected to submit their new round of nationally determined contributions (NDCs) by the end of the year to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change. The process may be delayed for some nations due to the pandemic, but China may still publish its enhanced NDC in the coming months. In March, China will also publish its next five-year plan, which will set targets for the economy as well as energy and climate change.

“Current policies would not indicate that China is on track to meeting this goal,” said Angel Hsu, an expert on Chinese climate policy at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, referring to the 2060 pledge, “so it will be interesting to see the energy 14th Five-Year Plan and what targets and policies are included there that could give us an indication for how China may plan to reach this target in the long-term.”

Hsu said China’s announcement may also have ripple effects on other countries as they choose whether to more aggressively tackle climate change, in the absence of US leadership, approaching the next major UN negotiations on climate change (COP 26), which will be held in November 2021.

“For China, who is experiencing economic ramifications of Covid like every other country, to come out and make this kind of bold statement on carbon neutrality could potentially sway the balance of countries who have been taking a ‘wait and see’ approach to their enhanced ambition climate pledges ahead of COP-26,” Hsu said. Here’s hoping it does.

Lili Pike is a science, health, and environmental reporting (SHERP) master’s student at NYU and a freelance journalist with a focus on China.

Millions turn to Vox each month to understand what’s happening in the news, from the coronavirus crisis to a racial reckoning to what is, quite possibly, the most consequential presidential election of our lifetimes. Our mission has never been more vital than it is in this moment: to empower you through understanding. But our distinctive brand of explanatory journalism takes resources. Even when the economy and the news advertising market recovers, your support will be a critical part of sustaining our resource-intensive work. If you have already contributed, thank you. If you haven’t, please consider helping everyone make sense of an increasingly chaotic world: Contribute today from as little as $3.

Author: Lili Pike

Read More