Kaepernick’s lawyer and the NFL announced a confidential settlement in the grievance case on Friday.

More than 16 months after filing a formal complaint alleging that NFL team owners worked together to keep him off the field in the wake of his kneeling protest, former San Francisco 49ers quarterback Colin Kaepernick’s collusion grievance against the league has concluded with a confidential settlement, lawyers for Kaepernick and the NFL announced Friday.

The exact details of the settlement — which also included an agreement with player Eric Reid, who filed his own collusion grievance in 2018 — will not be announced due to a confidentiality agreement. The settlement was first revealed in a pair of Friday afternoon tweets posted by the NFL and Kaepernick’s lawyer, Mark Geragos.

— Mark Geragos (@markgeragos) February 15, 2019

“For the past several months, counsel for Mr. Kaepernick and Mr. Reid have engaged in an ongoing dialogue with representatives of the NFL,” the parties noted in a joint statement. ”As a result of those discussions, the parties have decided to resolve the pending grievances.”

Kaepernick won his first major victory in his grievance case last August when an NFL arbitrator ruled that he would allow Kaepernick’s grievance to proceed to an official trial phase. The trial was expected sometime this year, but the settlement announcement means that the case ends here.

In addition to the joint statement from Kaepernick’s attorney and the NFL, the settlement was also acknowledged in a Friday statement from the NFL Players Association, which advocates on the behalf of NFL athletes:

We continuously supported Colin and Eric from the start of their protests, participated with their lawyers throughout their legal proceedings and were prepared to participate in the upcoming trial in pursuit of both truth and justice for what we believe the NFL and its clubs did to them.

The group also expressed its satisfaction that Reid has since joined a new NFL team, and called for Kaepernick to also be given that chance.

The settlement ends a long battle between Kaepernick and the NFL, which has adamantly denied colluding to keep him from playing football after Kaepernick began kneeling during the national anthem to protest racial injustice and police violence. His protest later spread across the league, sparking condemnations from President Donald Trump, who has made opposition to the protests a key part of his political messaging. And while the settlement means that Kaepernick’s official case has ended, discourse on his impact on matters of race, patriotism, and activism are unlikely to end anytime soon.

A brief history of Kaepernick’s kneeling protests, explained

Kaepernick began his protests against police violence and racial inequality in 2016, first sitting and later kneeling during the national anthem. The act sparked a years-long debate about activism on the football field, as players throughout the league joined him by kneeling, raising fists, and locking arms.

Along with some fans, the protests drew the ire of President Donald Trump, whose comments turned the protests into a referendum on matters of race and patriotism.

As Trump’s criticism mounted both on the campaign trail and later from the White House, Kaepernick left the 49ers and became an unsigned free agent, last appearing in an NFL game in January 2017. Nine months later, he filed an official grievance against the NFL, alleging that the league’s teams colluded to keep him off the field as a result of his protest. Some of the NFL’s most powerful owners gave depositions in the case.

As a new NFL season began last fall, the league and its players remained deadlocked over an anthem rule intended to end the kneeling protests. That rule has since been suspended, but the protests were declining even before it was announced.

Still, Kaepernick’s image and the image of his protest has continued to loom large over the league. The athlete garnered a wave of praise — and backlash — for a Nike campaign he appeared in promoting the message “Believe in something, even if it means sacrificing everything.” It was one of many signs that Kaepernick’s protest and subsequent exile had made him into a powerful symbol in American culture.

Last August, Kaepernick lawyer Geragos announced that an arbitrator denied the NFL’s efforts to end the collusion grievance in its preliminary stage, giving Kaepernick a chance to officially make the case that he was blackballed by the NFL.

The news of his grievance sparked ongoing discussions of the ways the league’s handled the kneeling protests, but also opened a larger conversation about how the NFL treats its players, a relationship that has always been fraught due to the racial politics of the NFL’s predominantly white group of executives and team owners making decisions that affect a predominantly black group of athletes.

Kaepernick argued the NFL and its teams colluded to keep him off the field, which the league denied

Kaepernick became a free agent after opting out of his 49ers contract in March 2017, allowing him to sign with any team. He spoke to the Seattle Seahawks and Baltimore Ravens but wasn’t offered a contract with either. A string of other quarterbacks — some with statistically weaker performances than Kaepernick — found work in the NFL. This prompted observers to question whether Kaepernick was out of a job because of his protests.

Kaepernick formally demanded that the league answer that question in October 2017 when he filed his grievance, alleging that the NFL’s teams had colluded against him. In doing so, he asked the NFL’s arbitrator to determine if two or more teams, or NFL leadership in partnership with at least one team, worked together to keep him off the field because of his protest.

Due to the rules outlined in the NFL Players Association’s collective bargaining agreement with the league, a ruling in Kaepernick’s favor would not entitle him to a spot on a team, but he would receive a financial award amounting to roughly double what he would have made if he had stayed in the league.

”Principled and peaceful protest … should not be punished,” Geragos, Kaepernick’s attorney, said in a 2017 statement. “Athletes should not be denied employment based on partisan political provocation by the Executive Branch of our government.”

The NFL denied that this happened. “Teams make decisions (based) on what’s in the best interest of their team … and they make those decisions individually,” NFL Commissioner Roger Goodell said. The league regularly repeated that argument, saying there was no effort to collude against Kaepernick and that any team’s decision to keep him off the field was a decision made independently.

Some of the NFL’s argument was challenged. In May 2018, Yahoo Sports reported that in 2017, NFL executives contracted a poll asking fans if they thought Kaepernick should continue to play in the NFL. This, on its own, wouldn’t be enough to prove a conspiracy to keep Kaepernick off the field, but if the polling data was shared with teams and then influenced teams’ willingness to sign Kaepernick, that could have been a problem.

Denver Broncos general manager John Elway, one of several NFL figures deposed in the first stage of Kaepernick’s grievance, also muddied the waters in 2017 when he potentially violated the grievance’s gag order while speaking with reporters. “As I said in my deposition … I don’t know if I’m legally able to say this, but he’s [Kaepernick] had his chance to be here,” Elway said. “He passed it.”

Reporters noted that Elway offered Kaepernick a contract in 2016 but passed on him a year later, after the protests, despite Kaepernick’s improved numbers that season. Elway’s comments suggested that he had been asked about the 2016 offer in the deposition.

Kaepernick cleared the first hurdle in his collusion case — but collusion is very difficult to prove

To understand the process that led to the recent settlement, it’s helpful to explain exactly how collusion grievances are handled. First, collusion between teams to prevent a player from signing onto a team or playing is a violation of the NFL Players Association’s collective bargaining agreement with the league.

Collusion grievances don’t go to trial, although they do rely on a framework that borrows heavily from that sort of procedure. If the official hearing happened, Kaepernick’s team and the NFL would have been able to offer testimony, present evidence, and review footage.

All of this would occur behind closed doors, with arbitrator Stephen Burbank, who has worked to resolve disputes between the NFL and the Players Association for years and having the final say as to whether the NFL colluded against Kaepernick.

It presented an opportunity and a challenge for Kaepernick. In his preliminary ruling last year, Burbank determined that Kaepernick had enough evidence to move the case forward, which suggested he thought there was enough evidence to further investigate the collusion claim (although some experts, like Charles Grantham of the Center for Sport Management at Seton Hall University, argued that given the high-profile nature of the case, it was always very likely to get a hearing).

Burbank also opted not to remove any teams that he thought weren’t involved in collusion from the case, instead allowing the grievance against all 32 teams and the NFL executive leadership to continue. But this did not mean Burbank would find in Kaepernick’s favor once all evidence was presented in the next phase of the process.

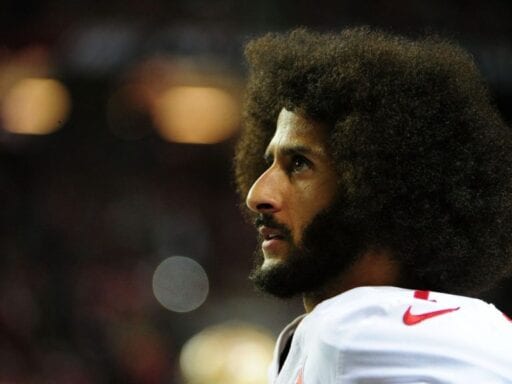

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/12861137/KapernickKneeling.jpg) Michael Zagaris/San Francisco 49ers via Getty Images

Michael Zagaris/San Francisco 49ers via Getty ImagesIn this process, it wouldn’t be enough to argue that Kaepernick — who led the 49ers to two conference championship games and the 2013 Super Bowl, and performed better while kneeling in the 2016-17 season than the year prior — is statistically a good enough player to play.

Kaepernick also couldn’t argue that a single owner who found his protest too hot to handle proved collusion; if that decision was reached independently, even if it was reached by each of the NFL’s team owners, it fails to meet that standard. Instead, Kaepernick had to prove that at least two teams, or the NFL and at least one team, worked together to keep him from playing.

Experts noted that it can be hard to find a smoking gun in these sorts of cases. “There’s a host of reasons why a club would individually or independently not offer him a contract,” Matt Mitten, executive director of the National Sports Law Institute at Marquette University Law School, told the New York Times in 2017. “So it will be tough for them to argue that there was a tacit agreement.”

That doesn’t mean it was impossible. Players in other leagues have won collusion grievances. Perhaps the most notable example of this occurred in the 1980s when players filed grievances against Major League Baseball, arguing that the league had restricted free agents. The arbitrator sided with the players, leading to a $280 million settlement.

But Kaepernick’s collusion grievance was also tied up in the owner-oriented nature of the NFL, which affords little power or recourse to its players. Even so, there was one figure who could help Kaepernick make the case that collusion played a role in what is likely to be a forced conclusion to his football career.

And that person was President Donald Trump.

NFL owners said they wanted to end Trump’s complaints about the protests. That could’ve helped Kaepernick’s case.

Trump has been very transparent about his feelings toward the NFL protests, particularly when it comes to his belief that players protesting racial injustice are disrespecting the symbols of America.

The claim dates back to his time on the campaign trail when he criticized Kaepernick’s protest, saying the player should “find a country that works better for him.” Since then, Trump has only ramped up his rhetoric, notably calling kneeling NFL players “sons of bitches” who should be fired last September.

A few weeks after that, Vice President Mike Pence left a football game after 49ers players knelt during the anthem (Trump took credit for Pence’s departure shortly thereafter). In March 2017, after Kaepernick became a free agent, Trump argued that NFL owners were avoiding the quarterback because they didn’t want to get a “nasty tweet” from the president.

Trump has eagerly claimed credit for Kaepernick no longer playing football and suggested that the NFL impose strict penalties on players who continue to protest, but that doesn’t necessarily imply he colluded with the league or team owners. After all, Trump, despite his earlier ambitions, is not an owner of an NFL team.

But as Michael McCann, a law professor and legal analyst for Sports Illustrated, explained, Trump still could be the catalyst for collusion within the NFL. That case could be made based on various comments from Trump and corresponding statements and policies taken by the league in recent months.

And some team owners — especially those who are among Trump’s most prominent supporters and donors — have made it clear that they are deeply worried about the president’s criticisms.

McCann explained last year:

Such a concern was documented in audio recordings of owners during an October 2017 meeting that centered on Kaepernick and the national anthem. This same concern resurfaced in June 2018 when Trump rescinded a White House invitation to the Super Bowl champion Philadelphia Eagles on account of his perception that Eagles players disagreed with him on the anthem (in reality, not one player on the Eagles kneeled during their Super Bowl season) and because only a handful of Eagles players were likely to attend.

According to Trump friend and Dallas Cowboys owner Jerry Jones, who also gave a deposition in Kaepernick’s collusion grievance earlier in 2018, the president has been pretty vocal about the political value of the NFL protests, telling Jones that attacking the protests was a “winning” issue.

In May 2018, the NFL announced (and later suspended) a new policy that would require players to stand on the field for the anthem or wait off field until it was over. According to ESPN, the desire to pass this rule was so strong that NFL owners did not even wait for a formal vote, instead relying on a hands vote to pass the anthem policy. The move has frustrated the Players Association, which entered talks with NFL execs in July 2018 in the hopes of creating a more agreeable anthem policy.

Again, none of was a smoking gun that proved collusion. But taken as a whole, these moments indicated that NFL owners had a strong desire to see an end to the player protests being used as a political weapon, and that appeasing Trump was a catalyst for that desire. The NFL has also worried that the protests are unpopular with fans, a theory that has been backed up in polls, although polling also shows significant racial and partisan divides in opinion over the protests.

All that made it more believable that at least some NFL owners might have colluded to curtail the protests by not signing Kaepernick, someone whom the president has repeatedly singled out when criticizing the NFL.

The settlement means that Kaepernick’s grievance will never receive an official verdict

When Burbank ruled that the case could go forward, Kaepernick and the NFL were left with two options: let things continue to a hearing, or settle before that happens. Given Kaepernick’s continued statements about the protests and the NFL’s response to them, it seemed unlikely that he would take the latter option, even if the league preferred it to avoid any further bad press. But since that happened, the case will not go to an official trial.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/12861097/KaepernickNikeAd.jpg) Justin Sullivan/Getty Images

Justin Sullivan/Getty ImagesA Kaepernick victory in the trial was by no means guaranteed, and both parties had the option to file an appeal after the final ruling. But if Burbank had ruled in Kaepernick’s favor, the case might have had a serious impact, on Kaepernick, the NFL, and other players.

First, there’s former 49ers safety Eric Reid, who joined Kaepernick in the kneeling protest and filed his own grievance against the NFL last year after he became another unsigned free agent in 2018. Reid eventually signed with the Carolina Panthers in September 2018.

There was also a chance that Kaepernick’s grievance might create a scenario where the current collective bargaining agreement could be scrapped, but that was always incredibly unlikely. Under the current agreement, if the NFLPA is part of a grievance where 14 teams are found to have colluded, then the NFLPA can call for a new agreement.

That didn’t happen, and Kaepernick’s and Reid’s grievances were eventually settled. And while the settlement is not an acknowledgment of guilt from the NFL, the fact that the settlement happened shortly before the trial was expected to start suggests that the league did not want to deal with a highly publicized fight against the former player.

It’s perhaps a testament to how Kaepernick sparked a tremendous shift that continues to affect the NFL’s public image and has ignited an ongoing national dialogue about race, sports, and protest. And while the future of Kaepernick’s football career remains uncertain, that change will be difficult to reverse.

Author: P.R. Lockhart

Read More