The DNC says no primary can be held after June 9 — but Covid-19 has some states ignoring the rules.

New York has delayed its 2020 presidential primary until June 23 due to coronavirus concerns, a delay that the Democratic party said could result in the state losing delegates at the national convention in July. New York is just the latest of more than a dozen states figuring out how to balance public health concerns with concluding a Democratic primary.

New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo announced the delay at his daily coronavirus press conference Saturday, saying, “I don’t think it’s wise to be bringing a lot of people to one location to vote, a lot of people touching one doorknob, a lot of people touching one pen.”

The move will be an easy one, he explained, because the state had a state- and congressional-level primary already scheduled for June 23.

But the choice to delay the Democratic contest could come with consequences. Democratic National Committee rules mandate states that push their primaries to a date after June 9 have their delegates reduced by 50 percent.

And the rules also say any candidate campaigning in a state with a contest outside of the DNC’s designated primary calendar will not be awarded any delegates from that state. Sen. Bernie Sanders and former Vice President Joe Biden, the last two candidates in the primary race, aren’t physically campaigning in New York (or any other state), but the DNC defines “campaigning” broadly as being inclusive of but “not limited to”:

Purchasing print, internet, or electronic advertising that reaches a significant percentage of the voters in the aforementioned state; hiring campaign workers; opening an office; making public appearances; holding news conferences; coordinating volunteer activities; sending mail, other than fundraising requests that are also sent to potential donors in other states; using paid or volunteer phoners or automated calls to contact voters; sending emails or establishing a website specific to that state; holding events to which Democratic voters are invited; attending events sponsored by state or local Democratic organizations; or paying for campaign materials to be used in such a state.

The DNC further notes its Rules and Bylaws Committee can add to this list and has final say over whether a campaign’s activities are in violation of this rule. That means that although, for instance, podcasting isn’t included in this list, Biden’s new podcast could perhaps be seen as being in violation of this rule, given it is distributed nationwide, including to New York, Louisiana, and Kentucky — all states that now have post-June 9 primaries.

In light of these rules, most states rescheduling their primaries set new dates just ahead of this June 9 cutoff. Pennsylvania, Connecticut, and Ohio, for example, joined a growing list of states holding primaries on June 2. Other places, like Puerto Rico, cut things a little closer: Its primary will be on June 7.

It is not yet clear whether these rules will be enforced, particularly now that the most delegate-rich state left on the calendar, New York, has chosen a delay, and the DNC has not yet responded to a request for clarifying comment. But DNC chairman Tom Perez did say in a mid-March statement that the committee would “continue to monitor the situation and work with state parties around their delegate selection plans, specifically allowing flexibility around how states elect their delegates to the national convention.”

How much flexibility remains to be seen. In the meantime, however, the DNC is making it plain that it doesn’t want states postponing primaries at all.

The DNC argues mail-in voting is the solution to the coronavirus voting issue

Following Ohio’s Super Tuesday III announcement that it would delay its primary, Perez said in a statement, “States that have not yet held primary elections should focus on implementing the aforementioned measures to make it easier and safer for voters to exercise their constitutional right to vote, instead of moving primaries to later in the cycle when timing around the virus remains unpredictable.”

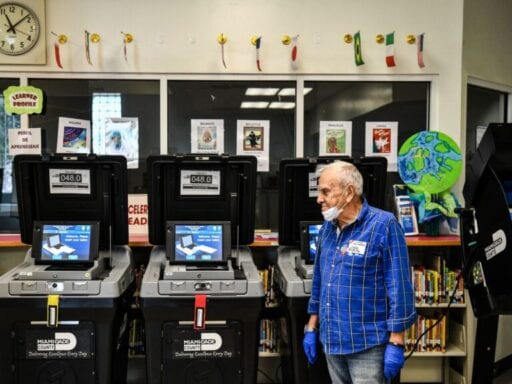

In a Sunday USA Today op-ed by Perez and six other Democratic Party leaders, the party expounded upon this point, arguing that states should simply expand their voting periods to at least 20 days before elections — and their voting hours — to allow voters to cast ballots in socially distant ways. This would not solve the problem Cuomo cited as his primary concern: that voters risk exposure by coming into contact with high-touch surfaces such as ballot pens and the handles of polling place doors.

To that end, the authors also suggest states work to expand their mail-in voting programs, writing:

States should automatically mail ballots to registered voters; voters should be able to mail back those ballots for free or with prepaid postage by the date of the primary; voters should also be able to drop off ballots at predesignated locations, as is the case in Arizona, or have someone else drop it off for them; and ballots should be accepted as long as they are postmarked by Election Day and received within 10 days of the election.

And the DNC is now committing to helping states pay for these reforms, with the leaders writing, “any state that voluntarily complies with such reforms will receive payments equal to the costs they’ve incurred.”

Ahead of November, Perez and his colleagues further pressed Congress and the White House to embrace a proposal by Sens. Amy Klobuchar and Ron Wyden that, as Vox’s Ella Nilsen has explained, “if 25 percent of US states declare an emergency … would trigger a requirement to allow any voter to vote from home via a mail-in ballot.” All states have done so, which would place the bill in effect if it were to become law as written.

Nilsen noted the bill’s authors hoped the proposal would be included in the Covid-19 stimulus package Congress passed last week; it was not, and it won’t be able to be taken up until at least April 20, when the Senate ends its current recess, if at all.

The ratification of such a proposal would go a long way toward addressing Perez’s second concern earlier this March, namely that the “timing around the virus remains unpredictable.”

While delays certainly allow states to strengthen — and in some cases fully develop — their vote-by-mail infrastructure, it is true that on June 23 or November 3 the United States may still find itself needing to maintain extreme social distancing practices. In fact, many experts say this is likely, and that unless a precise system of testing, surveillance, and tracking is developed, the United States may have to continue to shelter in place until a vaccine is developed, a process that could take until September 2021 — if not longer.

This means that Perez is correct in arguing the delays that have been decided on so far may not enfranchise those who would like to vote but are concerned about contracting the coronavirus. It is important to note, however, delays will re-enfranchise some voters: those infected with the virus during their state’s primary.

This is particularly true in New York. Saturday, Cuomo said the state is likely to see its case peak in three weeks — that is, right around April 28, the day it was meant to hold its presidential primary.

As of March 30, the state has nearly 60,000 confirmed cases, meaning more than 60,000 New Yorkers will be at home in bed or in hospitals on ventilators when its original primary date comes around. Not all of that number will be Democrats, but given New York is a solidly blue state, a large number of them will be, and the postponement should allow most of them to vote. Officials hope social distancing measures will force the state’s case count much lower, allowing more people to participate than would have otherwise been able to.

Public health experts like Dr. Deborah Birx and Dr. Anthony Fauci have both said the US can expect confirmed case counts to go up in the weeks to come and that it takes time to see the benefits of social distancing. This would suggest that delaying primaries in general will allow them to be held at a time when fewer people are sick. But also that it would be wise to, as the DNC has recommended, adopt vote-by-mail measures that will keep people from having to travel to the polls.

Ultimately, the delays seem unlikely to change the course of the race

Before the full scope of the coronavirus pandemic became apparent, Biden appeared poised to become his party’s presidential nominee. A candidate needs 1,991 delegates to win the nomination without the aid of superdelegates, and with March’s contests behind him, Biden leads the delegate race with 1,168 pledged delegates to Sanders’s 884.

Before the restructuring of the primary calendar, contests in delegate-heavy states the former vice president was expected to win — like Georgia, Pennsylvania, and New York —meant he had the potential to come close to that 1,991 threshold by the end of April, or at the very least, amass so many delegates as to make it mathematically impossible for Sanders to catch up to him.

While this might seem to suggest the delays are beneficial to Sanders’s campaign, this does not currently seem to be the case. The next states scheduled to vote — Kansas, Nebraska, and West Virginia — all favor Biden.

None of these states has a massive number of delegates and much could change between now and June, facts giving Sanders little pressure to drop out. This makes it more likely both candidates will continue to campaign until the summer, in turn making it more difficult for the party to devote resources toward fundraising for its eventual nominee and toward making preparations for the general election against President Donald Trump.

Stripping states that vote post-June 9 of their delegates would further complicate Biden’s path to victory, as doing so would take at least 191 pledged delegates out of the equation. And punishing Sanders and Biden for campaigning in late voting states would have an even greater effect; all together, New York, Kentucky, and Louisiana have 382 delegates on offer, more than Texas and almost as many as California.

The DNC may be inclined to make an exception to current rules to let the primary process play out in a manner that would allow one man to claim a clean victory. Whether they do remains to be seen, but either way, come June 3, the nation should finally have a clearer view of who will be the Democratic nominee.

Author: Sean Collins

Read More