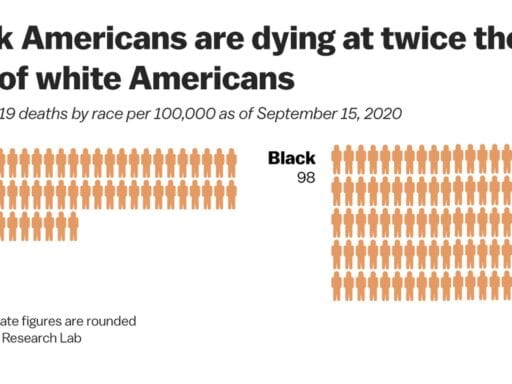

One in 1,000 Black Americans has died from Covid-19. For whites, it’s more like 1 in 2,100.

Covid-19 has torn through Black America, with the virus taking the lives of Black people in the US at twice the rate of white Americans.

All of America’s minorities, with the exception of Asian Americans, have seen worse outcomes than white people during the coronavirus pandemic. But Black Americans have fared worst of all, with about 1 in every 1,000 Black Americans dying from Covid-19 since February. That is about 40,000 people who have lost their lives. For their share of the US population, Black people are dying in the pandemic at twice the rate of white Americans, of whom about 1 in every 2,150 people has died.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/21927937/covid_death_rate_by_race.jpg) Christina Animashaun/Vox

Christina Animashaun/Vox(It should be noted that race data is not uniformly reported or reported at all for every Covid-19 death. But APM Research Lab and the Covid-19 Tracking Project have separately compiled data sets that roughly match.)

Indigenous Americans (1 death for every 1,220 people, per APM Research Lab), Pacific Islander Americans (1 in 1,400), and Latino Americans (1 in 1,540) are also dying at highly disproportionate rates compared to the white majority. Asian Americans have seen slightly fewer deaths per person than whites, with a 1 in 2,470 death rate.

In the first presidential debate, former Vice President Joe Biden cited the high Covid-19 death rate for Black Americans to argue his case that President Donald Trump has not been good for Black Americans.

“You talk about helping African Americans — 1 in 1,000 African Americans has been killed because of the coronavirus,” the Democratic nominee said. “And if he doesn’t do something quickly, by the end of the year, 1 in 500 will have been killed. 1 in 500 African Americans.”

The latter number would seem to refer to projections, not accepted by all experts, that 400,000 Americans could be dead from Covid-19 by the end of the year. The current total death count is about 207,000. Deaths have fallen from a second peak in August, when more than 1,000 people per day were dying on average, but signs of another spike in cases has added to fears that the winter months could see another wave of deaths.

While his Covid-19 response is regarded by many experts as a failure that contributed to unnecessary deaths among all of the nation’s racial groups, Trump does not bear all the responsibility for Covid-19’s toll on Black Americans. Long-standing health and economic disparities played an important role.

How health and economic inequities made Black Americans vulnerable to Covid-19

Housing segregation is arguably the root cause of those disparities, a manifestation of the systemic racism that has plagued Black Americans’ health since the age of slavery. It can be blamed on what was called “redlining” during the mid-20th century. Certain neighborhoods were given preference by the Federal Housing Administration. To receive loans to build housing developments or mortgages to buy one of those homes, real estate developers and homebuyers were directed to areas with “harmonious” racial groups (i.e. Black or white). Red lines were drawn around Black communities; white people did not get loans to build or buy houses in them, while Black people were only given loans to build or buy houses there.

Though redlining is no longer government policy, its consequences are still with us. According to the Economic Policy Institute, just 13 percent of white students attend a school that has a majority of Black students, while nearly 70 percent of Black students do. Black wealth trails badly behind white wealth; the former is more likely to live in an area with lower home values and, because of disparities in income, many Black Americans have not been able to build up enough wealth to buy a home in the first place.

And Black communities are facing other health crises. Black people disproportionately live in lower-income neighborhoods, which typically have more tobacco shops (which drives up smoking and therefore lung problems) and less access to fresh food (which drives up obesity, contributing to the high rates of diabetes and heart disease). David Williams, a Harvard public health and sociology professor, explained in a May 2020 editorial in JAMA all the ways the simple location of a person’s residence affects their health:

Segregation also adversely affects health because the concentration of poverty, poor-quality housing, and neighborhood environments leads to elevated exposure to chronic and acute psychosocial (eg, loss of loved ones, unemployment, violence) and environmental stressors, such as air and water pollution. Exposure to interpersonal discrimination is also linked to chronic disease risk. Greater exposure to and clustering of stressors contributes to the earlier onset of multiple chronic conditions (eg, hypertension, heart disease, diabetes, asthma), greater severity of disease, and poorer survival for African American individuals than white persons. For example, exposure to air pollution has been linked to hypertension and asthma, as well as more severe cases of and higher death rates due to COVID-19.

“I think of residential segregation by race as one of the upstream drivers,” Williams said in an interview earlier this year. “Social inequities are patterned by place, and opportunities to be healthy vary markedly at the neighborhood level.”

People with preexisting conditions such as asthma (which Black people are more likely to have than white Americans) and diabetes (likewise) and heart disease (which is less well managed for Black patients, based on death rates) are more likely to develop severe symptoms and die from Covid-19. Black Americans also have less access to doctors and hospitals, and a history of medical discrimination has created feelings of mistrust among many Black Americans toward the medical profession, which can lead to worse outcomes if patients delay getting care.

The systemic health care disparities have extended to Covid-19 testing. An analysis from FiveThirtyEight found that “Black and Hispanic people are more likely to experience longer wait times and understaffed testing centers.”

Black workers have also been on the front line, either in health care settings or for “essential” services that states kept open throughout the pandemic, which gives them more opportunities to be exposed to Covid-19. Black people are more likely than white people to be employed in the essential services that have been exempted from state stay-at-home orders, as Devan Hawkins covered for the Guardian. They are also more likely to work in health care and in hospitals and, in America as in other countries, health care workers make up a sizable share of Covid-19 cases.

But maybe the most searing evidence of the deep inequity of the Covid-19 pandemic is this: A June poll by the Washington Post and Ipsos found that 31 percent of Black Americans said they had known somebody who died from Covid-19.

Just 9 percent of white Americans could say the same.

Millions turn to Vox each month to understand what’s happening in the news, from the coronavirus crisis to a racial reckoning to what is, quite possibly, the most consequential presidential election of our lifetimes. Our mission has never been more vital than it is in this moment: to empower you through understanding. But our distinctive brand of explanatory journalism takes resources. Even when the economy and the news advertising market recovers, your support will be a critical part of sustaining our resource-intensive work. If you have already contributed, thank you. If you haven’t, please consider helping everyone make sense of an increasingly chaotic world: Contribute today from as little as $3.

Author: Dylan Scott

Read More