CRISPR revolutionized gene editing. Should we be worried?

Jennifer Doudna will be the first to tell you that she didn’t invent CRISPR, but she did help start the CRISPR revolution. In 2012, she was part of a small group of researchers at the University of California Berkeley who showed that CRISPR technology can be used to edit the genetic code of just about any organism quickly and precisely.

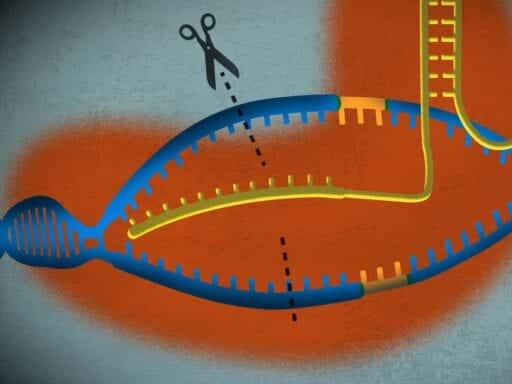

CRISPR gets its name from DNA fragments found in many bacteria. When bacteria successfully fight off invaders like viruses, they chop up the outside genetic material and store it as CRISPR sequences, creating a “database” of invader genes. Whenever a potential threat arrives, the bacteria can send defense enzymes (called Cas proteins) to search for CRISPR sequences in the invader; if one is found, the enzymes chop up its genetic material, killing it.

Doudna and her team realized that by giving Cas proteins genetic material resembling that of an invading organism, the proteins will cut DNA in a targeted, scalpel-like fashion. In the hands of scientists, the tool has radically simplified gene editing, the process of altering the biological instruction manual of living organisms.

After just eight years since its discovery, gene editing with CRISPR is still a very experimental technique. But the results so far have been promising: Researchers have used CRISPR to treat muscular dystrophy and Alzheimer’s disease in mice, fight drug-resistant bacteria, and create tastier tomatoes.

But editing human DNA is where the use of CRISPR becomes more controversial.

We’re starting to see early and positive results from preliminary trials of sickle cell therapies in humans. But as much as CRISPR has produced promising medical advances, the power of this gene-editing tech has a darker side.

Just a few months ago, Chinese scientist He Jiankui received a three-year jail sentence after using CRISPR to edit the genes of human embryos, twin girls who were born in November 2018.

In this episode of Reset, host Arielle Duhaime-Ross talks with Jennifer Doudna about the promise and peril in CRISPR’s future, what’s next, and how we can edit our genes safely and responsibly.

The transcript of their conversation that appears below has been edited for length and clarity.

Arielle Duhaime-Ross

Let’s talk about using CRISPR in humans. Where do you stand on this? How should we think about using CRISPR on people?

Jennifer Doudna

It’s very important to appreciate that there are fundamentally two different ways that CRISPR can be used clinically. When we say clinically, we’re talking about using it in human patients.

One of those ways is to use CRISPR in embryos, and if we do that, then it creates changes to the DNA of embryos that become part of that individual.

The other way to use CRISPR clinically is to use it in individuals. That means changing DNA in the cells of an individual, not in a way that becomes heritable by future generations, but just in a way that affects that individual patient.

That’s something that from the very beginning I have been a proponent of, because of the potential to correct disease-causing mutations.

What I’ve been really vocal about avoiding is the former situation where you would use CRISPR to create heritable changes. I’ve called initially for moratoria on that and more recently for global regulation around that.

Arielle Duhaime-Ross

So there are a few human clinical trials happening right now using CRISPR, and one in particular is a treatment for sickle cell anemia. To be clear, this treatment doesn’t make a change in people’s DNA that could be passed down to future generations. So when you hear that there are promising early results coming out of that trial, how do you feel?

Jennifer Doudna

Deeply moved, because I think for any of us working in science, the idea that our work could someday help someone with a health care situation that they and their families are facing, that’s really why we do our work. So I feel very excited about the potential of the technology.

Of course, I’m cautious. I want to make sure that it proceeds in a very appropriate, regulated fashion, and these trials that we’re seeing the early announcements for right now are going exactly down that path.

Assuming that those trials pan out, the big question will be how do we make sure that this technology is affordable and accessible to people that need it? That’s really the challenge that I’m now thinking more and more about and working on at the Innovative Genomics Institute.

Arielle Duhaime-Ross

You were one of the first people to hear about what the Chinese scientist He Jiankui did. He created the world’s first babies genetically edited with CRISPR, those two twin girls. Can you tell me the story of hearing about that for the first time?

Jennifer Doudna

So this goes back to the fall of 2018. I had been organizing the second International Summit on Human Genome Editing, which was scheduled to take place in November of 2018 in Hong Kong. And right before that meeting started, I received an email that had the subject line “Babies Born.” It was from Dr. He Jiankui and it was a very short message explaining that he and his colleagues had done clinical work to introduce embryos whose DNA had been altered with CRISPR to create a pregnancy that resulted in the birth of twin girls with altered genomes in China. And immediately, of course, this raised many questions about both the science and the ethics of what had been done.

Arielle Duhaime-Ross

So what happened next? You received this email and then what?

Jennifer Doudna

I flew out that night to Hong Kong so I would have a little bit of extra time before the meeting got started, and I ended up meeting with Dr. He before the meeting got started. He was already scheduled to be a speaker at that conference, and so when we met, we talked about what he was planning to present and also just trying to understand what had been done, first of all, and also why. What was his motivation? Why undertake something like this at this time?

Arielle Duhaime-Ross

Were you satisfied with the answer?

Jennifer Doudna

Well, I guess what was really kind of surprising to me honestly at the time was that although it seemed very clear to me and our colleagues that the work that had been done was really inappropriate for a number of reasons and really unethical.

This was not something that had really seemed to have occurred to him. He seemed to see himself more as a pioneer, somebody who was the first to bring this to people that might want to use it that way.

Arielle Duhaime-Ross

What would it take for you to feel comfortable about a clinical trial that would change a person’s DNA in a way that would allow that change to be passed on to that person’s offspring?

Jennifer Doudna

I think first and foremost, one would have to identify a real medical need for that and that real need is, right now, certainly, difficult to identify. But I think going forward, if there are real situations where an honest assessment says changing DNA is truly the best option for this family, for their children, etc., I think one would have to really want to have a whole pipeline of regulatory guidelines and a pathway for proceeding that would ensure safety of that kind of application. You would want to be able to follow their health outcomes over the course of their lifetime, especially in the early days of using the technology like that.

Arielle Duhaime-Ross

Do you often think about the potential ways that this technology down the line could end up being used? Do you often worry about things like eugenics?

Jennifer Doudna

I think that’s frankly right now still at the level of science fiction. It’s not something that’s going to happen anytime soon. That being said, I think it’s important that we right now grapple with the reality that we have in our hands a tool that in principle does enable that. It does allow control of genes and control of genes in families, and I think that it’s essential that we be tackling that issue right now, not running from it, but saying, look, this is a powerful tool. It has this potential and we need to already be thinking about how it could be used safely and how we appropriately regulate it.

Arielle Duhaime-Ross

Some people are very excitedly talking about CRISPR as a technology that could be used to prevent certain conditions, and I want to ask you about folks with disabilities. You sometimes hear people talk about “fixing deafness,” “fixing” conditions like dwarfism, and folks who are part of that community really get worried when they hear those things, because not everyone feels like they need to be fixed. They don’t feel broken. Where do you stand on that?

Jennifer Doudna

Your question really to me brings up broader considerations about … fundamentally, what does it mean to be human? What does it mean to embrace the diversity that we see across human cultures, human societies? To me, that’s one of the real joys of life.

So I think that to take it to an extreme, you could imagine a world where human beings have been sort of homogenized in a way, and we have a standard set of genes that we want people to inherit. Again, that’s really in the realm of science fiction.

But I think imagining that helps to put in perspective what we’re really talking about here, a situation where suppose that in the next decade or two, parents could go to an in vitro fertilization clinic and they could choose from a menu of genes.

Would this be a good thing or not? What if we could eliminate deafness, for example? Would that be a good thing or would it eliminate some of the richness from the world? It’s a hard question to answer, and I think it has to remain in the hands of individuals at some level.

Arielle Duhaime-Ross

When you hear these people talk about things like eliminating deafness … do you have a position? Have you figured out how you feel about this truly?

Jennifer Doudna

I think it’s a very individual choice to me. If you’re asking me if I were a prospective parent and this was a decision that I needed to make about my child, what would I do? Boy, that’s a hard one.

I have a wonderful son, and I see all the quirks that he has and things that just make him a wonderful person, and I think there’s a joy to that.

At the same time, if you knew ahead of time somehow that I had a genetic disorder that I knew he would be inheriting in some way and I could prevent it, well, I think, of course, as a parent, I would have that desire to prevent it.

I think these are some of the really interesting and really challenging questions that are now in front of us given that we have a technology that in principle, at least … will provide some of that type of capability to people. It’s a really profound and really interesting question, but it’s hard to answer.

Arielle Duhaime-Ross

Do you think that we’re going slow enough with CRISPR?

Jennifer Doudna

Boy, how to answer that. I guess the first thing I would say is that, the technology is so enabling for scientists that there’s no way to put the genie back in the bottle, at least at the level of research. And then, of course, at a whole different level, there’s the very tangible opportunities to affect people in positive ways that suffer from genetic disease. That is very exciting.

So I guess in the end, I don’t think it’s moving too fast. But I do think it’s moving fast for sure, and that it really does make it imperative that the scientific community deal right up front with the various challenges that we face to make sure it’s used safely.

Author: Daniel Markus

Read More