Immigration reform has long been elusive in Congress. Democrats may have a workaround.

After years of failed bipartisan talks on immigration reform, Democrats in Congress are pushing to go it alone and legalize millions of undocumented immigrants.

They’re hoping to provide a path to citizenship to several key groups: undocumented “DREAMers” who came to the US as children; people with Temporary Protected Status, a form of humanitarian protection typically conferred on citizens of countries suffering from natural disasters, armed conflict, or other extraordinary circumstances; farm workers; and other essential workers.

Though the specific legislative language has yet to be announced, Democrats are planning to include the proposal in their 2022 budget reconciliation package, which they could pass with a simple majority in Congress and without a single Republican vote.

It’s a risky strategy, but one Democrats believe is worth trying in order to break the yearslong immigration reform deadlock and improve the lives of millions who would otherwise continue to live in the shadows as a kind of permanent underclass, vulnerable to exploitation and to removal from a country where many of them have put down roots.

Budget reconciliation may be the Democrats’ best and only option in President Joe Biden’s first term to enact the most significant legalization program since 1986. And a recent federal court ruling halting new applications to the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program, which has shielded more than 800,000 DREAMers from deportation, has only increased the pressure on Democrats to act.

Biden had unveiled his own broader proposal for comprehensive immigration reform shortly after taking office, which would have aimed to legalize the entire population of more than 10.5 million undocumented immigrants living in the US.

Despite Democrats’ attempts to use that proposal as a starting point for bipartisan negotiations, there has been little interest from Republicans, who have sought to exploit Biden’s perceived weakness on border policy as a potential midterm strategy.

So Democrats are going it alone. But there is no certainty for now that reconciliation will work, as there are limitations on what kind of legislation can be passed through the process. As Biden acknowledged on Monday, the Senate parliamentarian will be the ultimate arbiter of whether it is allowed under budget rules.

“That’s for the parliamentarian to decide. Not for Joe Biden to decide,” he told reporters.

Democrats believe they have a good case for using budget reconciliation to pass immigration reform, given precedent from a 2005 reconciliation bill and what would be a significant economic windfall resulting from legalizing the groups of immigrants under discussion. But that might not be enough to convince the parliamentarian — and the price of failure could be meaningful progress on immigration reform in Biden’s first term.

“Focusing so heavily on reconciliation is a risky maneuver, since it relies entirely on the decision of the parliamentarian,” said Theresa Cardinal Brown, managing director of immigration and cross-border policy at the Bipartisan Policy Center. “I think that all avenues should be explored, and no one should put all their eggs in one basket.”

Democrats are targeting sympathetic groups of undocumented immigrants

Democrats’ proposal would legalize immigrant populations perceived as sympathetic by at least some members of both parties. Indeed, there have been bipartisan efforts to legalize DREAMers, immigrants with Temporary Protected Status (TPS), and farm workers with legislation that passed the House as recently as March.

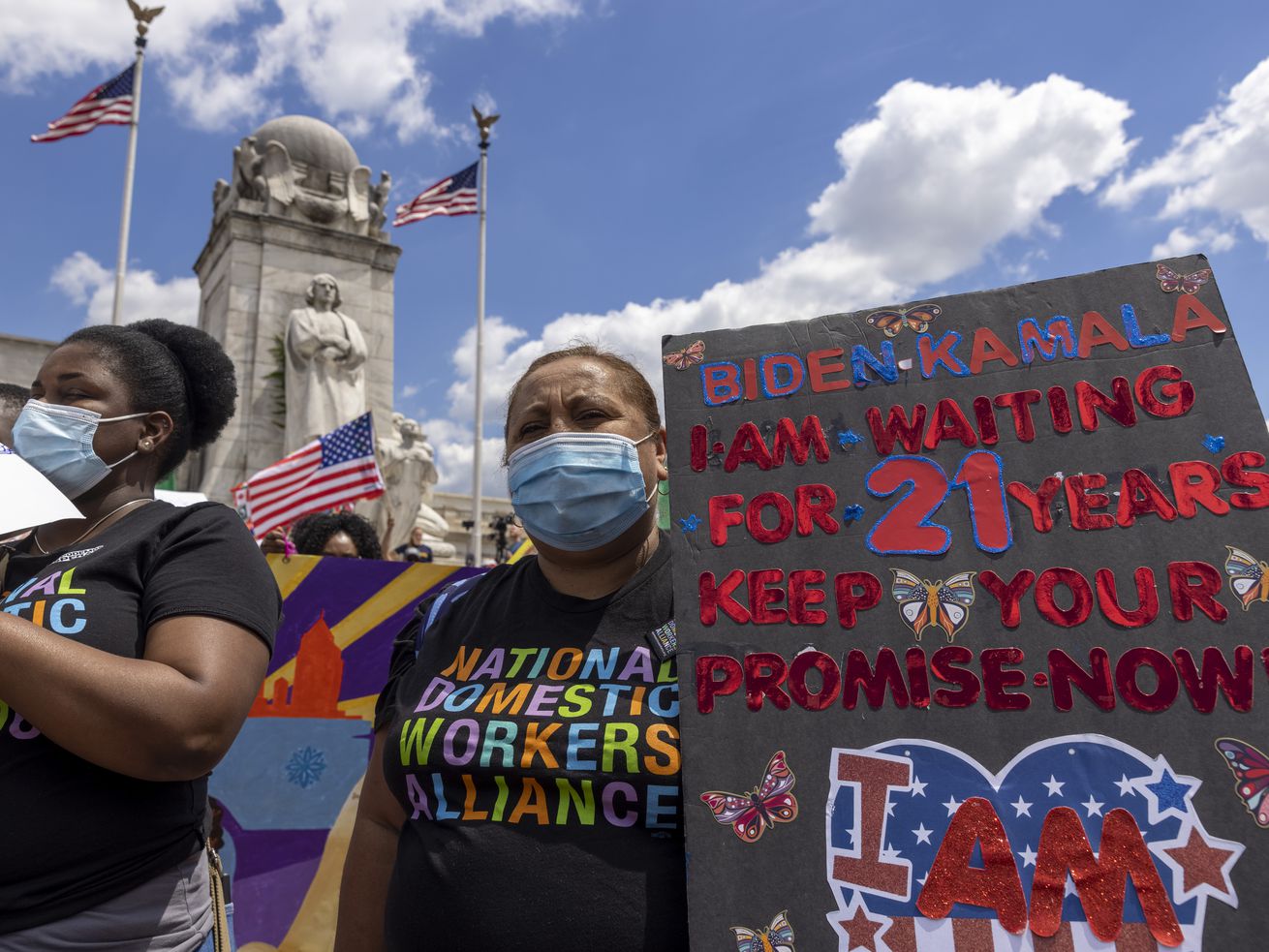

Many of those immigrants have been waiting for years, if not decades, for Congress to deliver them assurance that they can continue to live and work in the US free of fear of deportation — and Democrats’ efforts to deliver that through budget reconciliation are long overdue.

The first version of the DREAM Act, which would have offered a path to citizenship to DREAMers, was introduced in 2001, but time and time again, the legislation has failed to attract the necessary Republican votes to pass. The Obama-era DACA program has so far shielded them from deportation, despite being the target of attacks from immigration restrictionists since it was enacted in 2012.

For four years, President Donald Trump unsuccessfully sought to dismantle DACA and, for a time, halted new applications to the program. It revealed just how vulnerable DREAMers were to an administration with an anti-immigrant agenda.

Friday’s court decision from a federal judge in Texas is just the latest way in which DACA recipients’ legal status has come under threat. Under the decision, US Citizenship and Immigration Services cannot process or approve any new applications for DACA. That could affect a significant portion of the more than 1 million people eligible for DACA. People who currently have DACA can still apply for renewals, though that could change as the court case goes through the appeals process.

Immigrant advocates have argued that the decision has made a legislative solution for DREAMers all the more urgent. “Now, the responsibility rests entirely with the US Senate, and they need to take action,” Adonias Arevalo, national organizing director at the Latino rights group Poder Latinx, said in a statement.

Though budget reconciliation could be that solution, it might not come soon enough for people affected by the decision in the Texas case. An alternative might be a bipartisan bill that at least codifies the current DACA program, which “seems to be possible and may even be necessary sooner” given the more than 50,000 new applicants now in limbo at USCIS and the monthslong timeline for any possible reconciliation bill, Cardinal Brown said.

“There seems to be bipartisan support for doing at least that much, and I think it should be possible to do that and still push for larger legalization in the future,” she said.

TPS holders have similarly been waiting for Congress to offer them protection. About 400,000 citizens of El Salvador, Honduras, and Haiti have also been able to live and work in the US with TPS, but Trump tried to terminate their status, among nationals of other countries, starting in November 2017, against the advice of senior State Department officials. He argued that conditions in those countries have improved enough that their citizens can now safely return. But many of them have resided in the US for decades and have laid down roots, making it difficult for them to return to countries they no longer call home.

The push to legalize other essential workers began during the pandemic, as Democrats recognized that they not only deserve to remain in the US but that America’s ability to recover, both from a public health perspective and economically, demands that they do. There are more than 5 million undocumented essential workers living in the US — almost three in four undocumented immigrants in the workforce. That includes an estimated 1.7 million workers in the nation’s food supply chain, 236,000 working as health care providers, and 188,000 who are responsible for keeping hospitals, nursing homes, and labs running.

It’s not yet clear exactly how many of these workers Democrats are seeking to legalize. California Sen. Alex Padilla and Texas Rep. Joaquin Castro, among other Democrats, have previously proposed offering a path to citizenship to 2 million of essential workers’ family members as well, but the reconciliation proposal might not be that broad.

The bill could also legalize the nation’s estimated 1.1 million to 1.7 million undocumented farmworkers. The US agricultural industry has relied on immigrant labor for decades, dating back to the Bracero Program in the 1940s that allowed millions of Mexicans to come to the US as farm workers. Another large influx of unauthorized workers came during the 1990s before a slowdown that started around 2008, leaving agricultural employers unable to replace an aging workforce.

Congress has been wrestling with how to respond to labor shortages in agriculture and reduce the industry’s reliance on undocumented workers ever since. That mission took on new urgency under Trump, following his administration’s immigration raids targeting the agricultural sector. At one raid in August 2019, 680 workers were arrested at two poultry plants in Mississippi.

Can Democrats pass immigration reform through reconciliation? It’s complicated.

The Democratic caucus seems to be presenting a unified front in supporting the inclusion of provisions to legalize some undocumented immigrants in a reconciliation package. West Virginia Sen. Joe Manchin, a key moderate, has said he supports it, just as he did a 2013 comprehensive immigration reform package that passed the Senate but ultimately failed in the House. It’s likely that other moderates will follow suit.

“I’m a 2013 immigration supporter. I thought that was a great bill. If we had that bill then, we wouldn’t have the problems we’d have today,” he told reporters last week.

But even if Democrats are comfortable using reconciliation to pass immigration reform, the Senate parliamentarian, an unelected official, might not be. That has raised concerns among some immigrant advocates on the left:

The future of 11 million undocumented people shouldn’t be determined by an unelected Senate staffer.

If the parliamentarian rules against a pathway to citizenship, we must put aside the filibuster and finally address the issue of immigration. https://t.co/f0GaRJQwGz

— Julián Castro (@JulianCastro) July 19, 2021

But barring a bipartisan breakthrough that has been elusive for years or the elimination of the filibuster, there isn’t any way around the parliamentarian’s ruling. It’s what ultimately doomed Democrats’ proposal earlier this year to increase the federal minimum wage to $15 an hour by 2025.

Democrats have argued that precedent is on their side. In 2005, the then-Republican-controlled Senate passed its own reconciliation bill including several immigration provisions that would have effectively increased the number of green cards issued annually. It would have allowed any unused green cards under the annual caps set by Congress to be issued the following year, as well as excluded the family members of foreign workers from counting toward the caps.

The provisions didn’t ultimately make it into the final version of the bill that was passed by the House, but the fact that they passed the Senate without objection from the parliamentarian or members of Congress arguing that it violated budget rules could indicate that Democrats’ latest proposal will pass scrutiny. The late Sen. Robert Byrd, who authored the rules about legislation that can be passed via reconciliation, didn’t even challenge the provisions on that basis at the time.

“I think it’s a fairly strong precedent, and other folks who worked on the 2005 package agree,” said Philip Wolgin, managing director for immigration policy at the Center for American Progress, a left-wing think tank. “But I do know the parliamentarian hasn’t ruled on this. So it is still an open question.”

What’s more, Democrats think they can argue that the immigration provisions have direct budget impacts — not ones that are “merely incidental” to the policy goal — as required under budget rules. Though the federal government would have to incur $126 billion in costs at the outset to process new green card applications, the provisions would carry massive economic benefits.

Just providing DREAMers, TPS holders, and undocumented essential workers with a path to citizenship would increase GDP by a cumulative total of $1.5 trillion over 10 years and create 400,800 new jobs, not even accounting for the potential economic windfall for those immigrants’ children, according to estimates from the Center for American Progress. The same analysis notes after 10 years, those workers would see their annual wages increase by $13,500, and all Americans would see higher wages by an annual $600.

“There’s a pretty small short-term cost to the government, but really big economic benefits to ordinary Americans all across the country in the form of higher wages and new jobs,” Wolgin said.

Still, some budget experts aren’t convinced that the kind of immigration legislation that Democrats want to pass would have direct budgetary impacts. For example, raising fees associated with applying for visas or green cards to raise revenues at the immigration agencies would qualify, but increasing the number of people eligible for green cards probably doesn’t, said Bill Hoagland, senior vice president at the Bipartisan Policy Center.

“This whole process was intended to be a fiscal exercise — not one in which major public policy was to be implemented through this fast track,” he said. “This is not what the authors of the Budget Act had ever envisioned.”

Author: Nicole Narea

Read More