There are three threats facing American democracy right now. The For the People Act left some unaddressed.

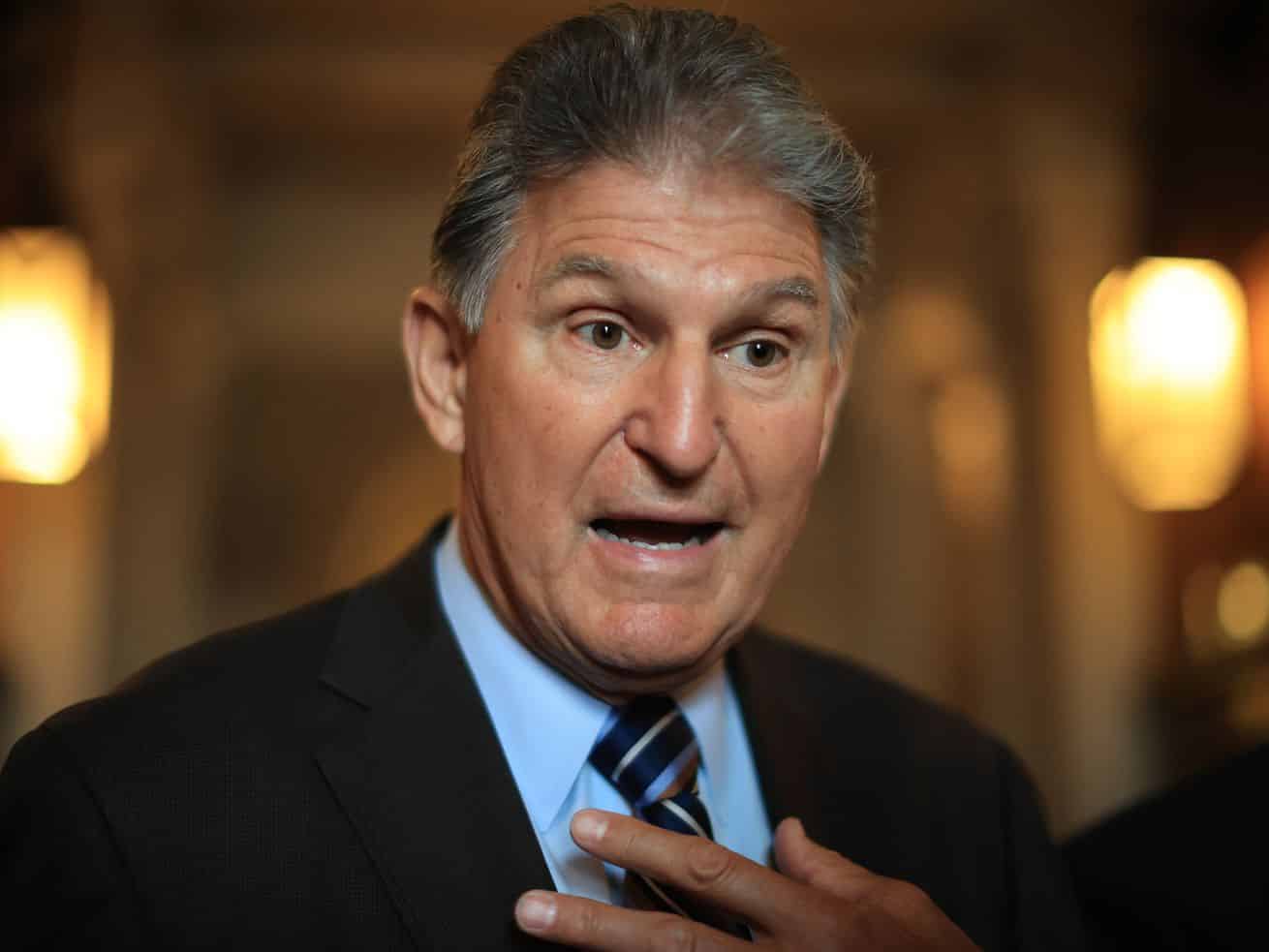

Sen. Joe Manchin (D-WV) torpedoed Democrats’ big voting rights bill Sunday, announcing in an op-ed that he would vote against the For the People Act this month. This is hardly a surprise — the bill was already doomed by the Senate filibuster — but Manchin’s opposition means it will lack even 50 votes in the chamber, and cuts off at the knees activists’ push for Democrats to abolish the filibuster in order to pass the bill.

Progressives are furious. Many liberals now argue that the For the People Act (often referred to as “HR 1” or “S 1,” its numbering in each chamber) is the crucial, must-pass legislation that would save the country from the threat the Republican Party poses to democracy — if only Democrats could work up the guts to ram it through.

“We may be living through a brief interregnum before American democracy is strangled for a generation,” New York Times columnist Michelle Goldberg recently wrote. “Two Democratic senators, Kyrsten Sinema and Joe Manchin, could save us by joining their colleagues in breaking the filibuster and passing new voting rights legislation. But they prefer not to.”

Yet while the bill would make some significant changes if it became law, it would fall far short of meeting that standard. The reality is that there are three distinct threats facing American democracy right now, and the For the People Act addresses, at most, one and a half of them.

Still, the bill, flawed as it is, would be better than nothing. And, despite Manchin’s professed hopes for a more limited bipartisan deal, nothing is what we’ll likely now get.

The three threats to democracy

Since former President Donald Trump tried to overturn the results of the 2020 election and various GOP-controlled states subsequently passed new laws restricting voting, there’s been a lot of focus among mainstream and progressive commentators about how the Republican Party is a threat to democracy.

But much of this commentary tends to conflate disparate issues that would have different policy solutions. We can break the threats to democracy into three categories:

1) Voting access: Republicans have passed various state laws attempting to make it more difficult for more people to vote. Here, Democrats believe the main issue is voter suppression (or lack of voter access) on the state level, with its impacts deliberately targeting nonwhite voters.

2) Structural biases: Many features of the US electoral system currently seem to give Republicans a strong chance of winning elections without getting a majority of voters. This includes gerrymandering in the US House of Representatives and in state legislatures, but also the Senate’s bias toward rural voters, and the Electoral College.

3) Actually overturning results: This was the main issue at the end of last year, as Trump tried to influence state-level officeholders and members of Congress to make him the winner instead of Biden, under bogus pretexts. Trump failed, but many Democrats fear he or another Republican could have more success at this in 2024.

The For the People Act would tackle No. 1 (voting access). It would address a limited part of No. 2 (just the gerrymandered House). And it would leave No. 3 (overturning results) basically unaddressed.

What the bill would and wouldn’t do about these threats

Voting access is where the For the People Act would bring the biggest changes. For all federal elections, it would require automatic voter registration, same-day registration, and at least two weeks of early voting, restore voting rights to all felons who have completed their terms of incarceration, allow registered voters lacking IDs to submit a sworn written statement instead, and attempt to limit voter roll purges.

This is a big deal because it would be a national standard for voting access in federal elections, counteracting state-level vote suppression laws. Some quantitative analysts do believe the partisan effects of vote restriction laws are overstated, and that such laws simply don’t affect turnout enough to swing any but the closest elections. But of course, making it easier for people to vote can be a good thing even if it doesn’t change election outcomes.

As far as structural biases, the bill’s near-term effect would be creating new standards for what would count as illegal partisan gerrymandering of the House of Representatives. If state legislatures produce maps that violate these standards, their opponents can sue — and the matter will be sent to federal judges to sort out. Some critics, such as Matt Yglesias, have argued that these standards would fall short of what’s necessary, and that proportional reforms would be better.

A larger point, though, is that many other structural biases of American democracy would remain in place even if the bill was passed. The Senate’s GOP lean is untouched — no new Democratic-leaning states would be added from this bill. The Electoral College is untouched (you need a constitutional amendment to change that). And state legislatures would remain free to gerrymander. Some of these issues are flat-out impossible to address in a bill like this, but the point is that many pro-GOP structural biases would remain even if it became law.

Finally, the For the People Act is particularly weak on any attempts to address the problem of political attempts to overturn legitimate election results — the main risk for democracy that looked so perilous in 2020. That’s because the bill was largely written before that crisis took place. Still, the New York Times editorial board points out that the bill fails “to address some of the clearest threats to democracy, especially the prospect that state officials will seek to overturn the will of voters.”

The most likely outcome here is: nothing passes

So the For the People Act was overhyped. It is simply not true that this bill would have saved American democracy — it would have made some worthwhile changes while leaving many more challenging topics unaddressed.

It’s also worth keeping in mind that passing it at all would have required a bitter partisan battle, including a Senate rules change. When I interviewed Manchin for a profile in April, he told me this was his main issue in the bill, saying, “How in the world could you, with the tension we have right now, allow a voting bill to restructure the voting of America on a partisan line?”

Progressives pointed out in response that Republicans in the states have been happily restructuring voting along partisan lines, and that Trump and his backers are still trying to cast doubt on the 2020 results with ludicrous “audits.”

But Manchin’s main misgiving was his fear that national Democratic action would radicalize Republicans even further. He told me that 20 to 25 percent of the public already doesn’t trust the system, and that a party-line overhaul would “guarantee” that number would increase, leading to more “anarchy” like that at the Capitol on January 6.

That is why Manchin has embarked on this quest for bipartisan voting reform. He’s reiterated his support for expanding a separate bill, the John Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act, in an idea my colleague Ian Millhiser has praised. Yet currently, he has just one Republican on board: Sen. Lisa Murkowski (R-AK). He’d need 10 Republican senators to pass it.

That seems unlikely on a topic now as charged, and as frequently subject to Trump’s demagoguery, as voting rights. And that polarization is the larger issue here. There’s been endless second-guessing of how an alternative bill could have been better at winning Republican votes. But so long as the filibuster’s 60-vote threshold is in place, any bill is likely doomed, except perhaps one that’s so watered down that it would achieve nothing of note.

Author: Andrew Prokop

Read More