A House vote brings the Equal Rights Amendment closer to passage, but it still has a long road ahead.

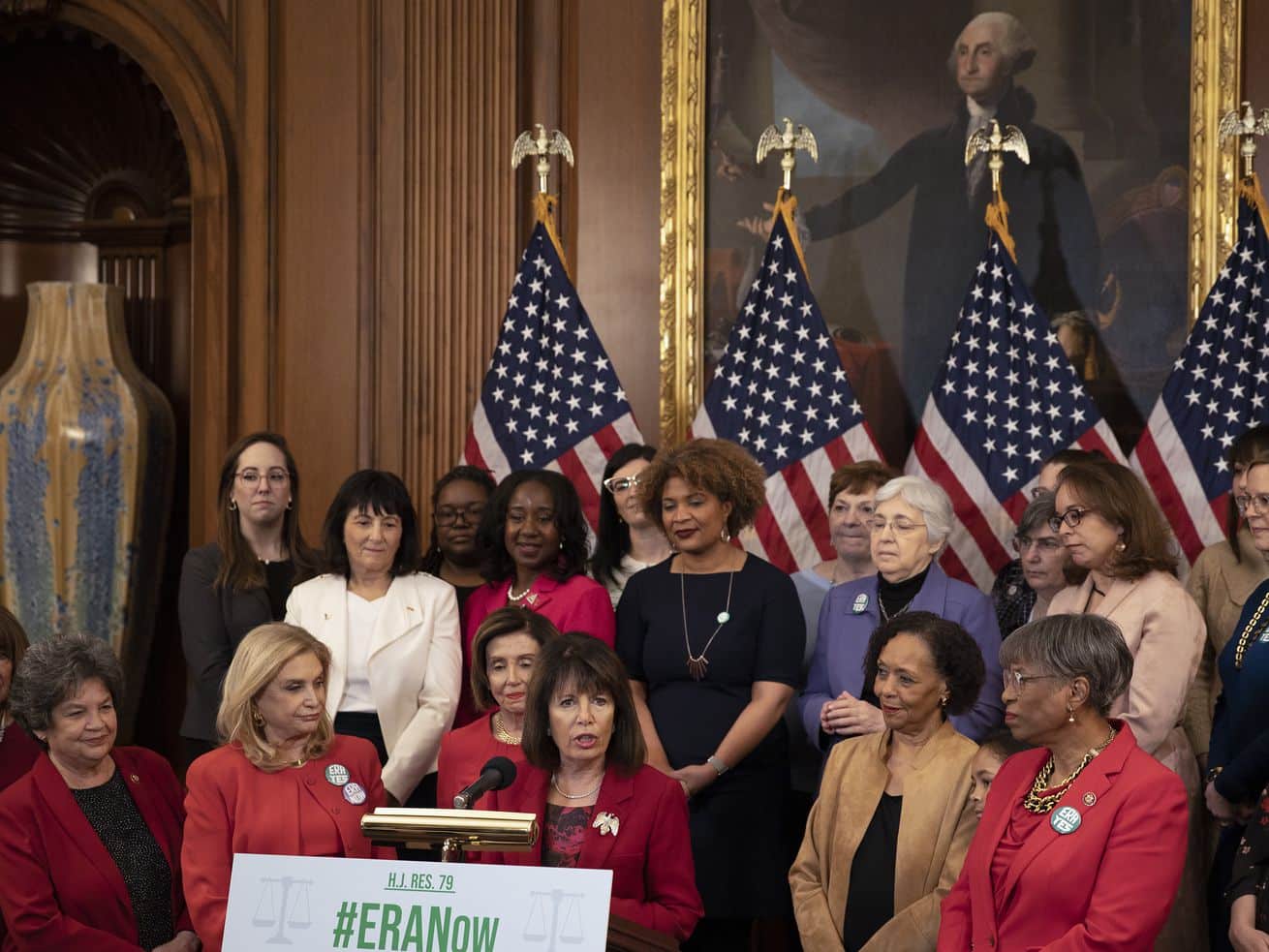

The House of Representatives voted on Wednesday to remove a key stumbling block for the Equal Rights Amendment, which would enshrine the principle of gender equality in the US Constitution.

First introduced in 1923, the amendment would ban discrimination on the basis of sex, paving the way for people of all genders to challenge anything from unequal pay to restrictions on abortion. But the amendment has had a long road in American politics, and that road is far from ended.

The ERA passed Congress with bipartisan support in 1972 but still had to be ratified by three-quarters of the states, a process that ended up taking nearly 40 years. Last January, Virginia became the 38th state to ratify the amendment, pushing it over the finish line. But there was a problem: Congress had set a ratification deadline of 1982. The resolution passed today, introduced by Reps. Jackie Speier (D-CA) and Tom Reed (R-NY), removes the deadline so that the process can move forward.

There are still many obstacles ahead; the resolution needs to pass the Senate, where it will likely face Republican opposition. It’s also likely to face a legal challenge, as the Department of Justice under President Donald Trump issued a memo stating that Congress could not revive a proposed amendment after the ratification deadline had expired. Still, the vote Wednesday is a major step toward an amendment that, with a Democratic-controlled Congress and a new president in the White House, now stands a better chance of becoming law.

Wednesday’s vote removes one obstacle to the ERA. There are many more ahead.

The Equal Rights Amendment is simple. Here’s the text:

Section 1: Equality of rights under the law shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any state on account of sex.

Section 2: The Congress shall have the power to enforce, by appropriate legislation, the provisions of this article.

Section 3: This amendment shall take effect two years after the date of ratification.

But these few words have been wending their way through American politics for nearly 100 years, as Vox’s Emily Stewart writes. First introduced in 1923, it passed Congress with bipartisan support in 1972. But because it’s a constitutional amendment, it still had to be ratified by three-quarters of the states, or 38 out of 50.

Thirty-five states ratified the amendment quickly, but then momentum slowed, in part due to the work of anti-feminist advocates like Phyllis Schlafly in the mid- to late 1970s who argued that the amendment would undermine women’s role as wives and mothers, expand abortion, and even make women eligible for the draft (supporters of the amendment argue that, actually, Congress already has the power to draft women). However, things have picked up again in recent years, with Nevada ratifying the amendment in 2017, Illinois in 2018, and Virginia in 2020.

“In passing this resolution, we’re finally on record as supporting women’s rights as human beings, equal to men,” Virginia Del. Jennifer Carroll Foy, sponsor of the state’s ratification resolution, said in a statement at the time.

But the deadline was a problem. The House of Representatives passed a resolution to remove it last year, but it didn’t receive a vote in the Senate, then under Republican control. Meanwhile, some states actively fought the amendment. In 2019, Louisiana, Alabama, and South Dakota filed a lawsuit in an effort to force the federal government to let the 1982 deadline stand. And President Trump’s Justice Department issued guidance last January stating that Congress does not have the power to change the deadline.

Now, however, Democrats control the Senate, and the resolution is likely to come to a vote, at a minimum. It’s still unlikely to gain a filibuster-proof majority, with Sens. Susan Collins of Maine and Lisa Murkowski of Alaska the only Republicans supporting it so far.

And even if it did pass the Senate, the resolution could face legal trouble, especially since several states, including South Dakota and Tennessee, have actually rescinded their ratification since 1972. Even Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, a champion of women’s rights, saw this as a problem. “If you count a latecomer on the plus side,” she said in a 2020 appearance, “how can you disregard states that said, ‘We’ve changed our minds?’”

Still, the amendment has something now that it didn’t have last year: the support of the president. Biden said during his campaign last year that he would “proudly advocate for Congress to recognize that three-fourths of states have ratified the amendment and take action so our Constitution makes clear that any government-related discrimination against women is unconstitutional.”

Advocates say passing the ERA would send a crucial message on gender equality

If it eventually does pass, advocates say the ERA would send an important message of gender equality to the entire country. Right now, the Constitution doesn’t explicitly address sex discrimination at all. The ERA would change that, Emily Martin, vice president for education and workplace justice at the National Women’s Law Center, told Vox last year. “It would, at the most fundamental level, recognize that gender equality is a foundational principle for the United States.”

There are laws on the books that ban sex discrimination in some arenas. The Equal Pay Act, for example, requires that men and women get equal pay for equal work. But, Foy told Vox last year, “laws can be changed just as easily as legislators change their minds” — a constitutional amendment is more permanent.

A constitutional amendment would also provide more tools to challenge discriminatory laws or practices in court. Federal courts have interpreted the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment as conferring some protection against sex discrimination, Martin said. But adding an explicit ban on such discrimination in the Constitution would likely force courts to take the issue much more seriously.

And it wouldn’t just affect women’s rights. By banning discrimination on the basis of sex, it could implicitly prohibit discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity as well, offering protections to gay and trans people regardless of their gender. The Supreme Court ruling last year in Bostock v. Clayton County, Georgia, which found that discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation was a form of sex discrimination, could bolster these protections if the ERA were to pass.

The effort to pass the ERA will strengthen activism for gender equality around the country, Martin said. In recent years, “we’ve seen this need and hunger and energy around women’s organizing, around women demanding equality,” she explained. “The push for the Equal Rights Amendment is part of that and builds on that.”

Author: Anna North

Read More