Haunted by their failure to pass a climate bill in 2009, some Democrats are vowing “no climate, no deal.”

Democrats tried to pass a big climate bill the last time they controlled the White House and Congress. It failed in a Senate with a bigger Democratic majority than the one they currently have.

More than 10 years after that bill — commonly known by the names of its co-authors (then-Rep. Henry Waxman and then-Rep. and now Sen. Ed Markey) — died without getting a vote in the US Senate, the United States is seeing more severe impacts of climate change. In recent days, an intense “heat dome” has scorched the West, one of many heat waves scientists say climate change is making worse. A group of Democratic senators fears that the coming months may present their last, best hope to actually do something about it.

“The time to do something was 20 years ago,” Sen. Martin Heinrich (D-NM) told me recently. “The second-best time to do something is now.”

Democrats are now pinning their climate hopes on President Joe Biden’s initial $2 trillion American Jobs Plan, which has major investments in clean energy, electric vehicles, and climate resilience. But much like 2010, nothing is certain. As the White House negotiates with a bipartisan group of senators on a slimmed-down infrastructure bill, progressive senators are worried that climate provisions of the bill will be minimized or stripped out. They’re sounding the alarm about the nation’s future if Congress — yet again — fails to pass major climate legislation.

“I’m terrified of what happens if we don’t act,” Sen. Ben Ray Lujan (D-NM) said. Heinrich, his Senate colleague in New Mexico, added, “My state is burning up.”

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22675364/GettyImages_1232927726.jpg) Gina Ferazzi/Los Angeles Times/Getty Images

Gina Ferazzi/Los Angeles Times/Getty ImagesBiden administration officials insist they can still hit ambitious new greenhouse gas emission reductions even if Congress doesn’t pass serious investments in clean energy and electric vehicles. But some close to the White House are doubtful a clean energy revolution can happen without action from Congress.

John Podesta, President Barack Obama’s former climate adviser, told me that even though Biden’s executive branch can push regulations and green-light clean energy projects on its own, a lot depends on how much Congress invests in clean energy before the 2022 midterms — when Republicans will have a chance to take back the House and Senate.

Biden “needs the investments, and a lot rides on, does he get the things he’s proposed in the American Jobs Plan?” Podesta said. “You can get some things going, but boy, I think they’re pretty dependent on some of the things [Congress] puts forth.”

And progressives are also worried what not delivering on a bold climate and infrastructure package could mean for the 2022 midterms, which largely hinge on turning out a fired-up Democratic base. More liberal lawmakers are coalescing around a new slogan: “No climate, no deal.”

“We’re not going to be able to get votes for a bill that does not seriously address the climate crisis,” Rep. Pramila Jayapal (D-WA), the chair of the Congressional Progressive Caucus, said.

The tepid economic recovery under Obama pushed Democrats to go big on recent stimulus. Many also learned a darker lesson about opportunities to pass climate legislation: The stakes of inaction are incredibly high.

Why the 2009 climate bill failed

Fresh off resounding victories in the White House and Congress in the 2008 election, Democrats had an ambitious list of policy proposals. Combatting climate change was a big priority, but it fell behind passing economic stimulus, expanding health care, and a financial reform bill after the recent economic crash.

For about a six-month window from summer 2009 to January 2010, Democrats had the 60 votes needed for a filibuster-proof majority. But that changed when Republican Scott Brown won the special Senate election in Massachusetts to fill the seat of the late Democratic Sen. Ted Kennedy.

“We thought we had more time with that supermajority than we ended up having,” Sen. Debbie Stabenow (D-MI), a member of Senate Democratic leadership, told me in an interview last summer. “Sen. Byrd died and Sen. Kennedy died, and we only had a matter of months and got the [Affordable Care Act] done, an economic stimulus package, and Dodd-Frank done.”

Work on the Waxman-Markey climate bill began in the US House, where it would continue for months of drafting and committee input. The officially titled “American Clean Energy and Security Act” was introduced in May 2009, weighing in at 1,400 pages.

Democrats’ plan would have capped the nation’s greenhouse gas emissions at a lower level, giving fossil fuel companies the ability to buy emissions offsets to hit their targets, or pay up if they went over. They settled on the cap-and-trade model in part because it was something that past Republican presidents had embraced. President George H.W. Bush proposed a cap-and-trade system as part of the 1990 Clean Air Act to help reduce sulfur emissions — and many Republican senators voted for it.

Indeed, the Waxman-Markey cap-and-trade bill was controversial among climate activists and experts who thought it was too friendly to big business and called for a carbon tax instead. The bill also contained funding for many of the things Biden is trying to do today, including incentives to support more electric vehicles and clean energy.

The bill squeaked through the House on a vote of 219-212 in June 2009, after months of work and whipping votes by Pelosi’s team. It never even made it to the floor of the Senate, because then-Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid had lost his supermajority with the Massachusetts election, and Democrats were suddenly staring down a set of tough midterms in the House and Senate.

“The votes weren’t there,” said Jim Manley, a former spokesperson for Reid. “I found that some of the worst vote counters around were in the environmental community at this time. I don’t blame them for trying.” Democrats’ big climate bill died in the Senate in 2010.

That history is a warning for Democrats today, who have no margin for error in their current 50-50 Senate, where Vice President Kamala Harris gives them one vote to break ties.

Looking back, a number of things set Waxman-Markey’s demise in motion, current and former lawmakers and staff told me. Democrats’ big climate bill was too in the weeds, was introduced when the country was still in a painful economic recession, and wasn’t the top priority. And even though Democrats’ climate bill was modeled on a Republican idea, Republicans pounced on it as a job killer, taking a do-nothing stance on climate in the process.

“It was a very tenuous economic time in a deeper, more profound way than currently,” said John Lawrence, who was chief of staff to House Speaker Nancy Pelosi at the time. “It was difficult to figure out where to put a big new controversial bill that looked to some people like it would compound problems impacting the economy rather than alleviating it.”

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22675378/GettyImages_88709078.jpg) Alex Wong/Getty Images

Alex Wong/Getty ImagesSen. Tammy Baldwin (D-WI), who was serving on the House Energy and Commerce Committee at the time, said that cap and trade was too complicated for voters to understand. Democrats need to improve their messaging, tying a climate and clean energy agenda to a clear message about jobs, she said.

“Lessons learned [are] that we have to be able to show how we’re protecting working people, how we’re creating new job opportunities, and how we’re protecting the planet,” said Baldwin. “We have to be very proactive, not just policy nerds.”

Ultimately, Waxman-Markey’s failure in 2010 meant that what Obama feared came to pass. The vast majority of Obama’s climate change agenda happened through the executive branch, with regulations on vehicles and electrical appliances, and the creation of the Clean Power Plan. Obama officials assumed that 2016 Democratic nominee Hillary Clinton would build on that, but Obama’s successor was instead President Donald Trump.

It hasn’t all been bad. As the Atlantic’s Robinson Meyer recently wrote, the US was still able to hit — even slightly exceed — the carbon emissions targets Waxman-Markey laid out (though, as Meyer points out, it’s impossible to know how much more emissions could have been avoided if the bill had passed). Even then, it still hasn’t been enough to stop the devastating impacts of climate change around the world and in the US.

All of this has convinced climate-minded Democrats that action from Congress is needed to push the US into a clean energy transition. While Podesta told E&E News in 2016 that Waxman-Markey’s failure had shown him that strong executive branch action was the way to go on climate, five years later, he believes that action from Congress is essential, he told me.

Biden “needs a big jolt of federal investment to grease the gears,” Podesta said.

“No climate, no deal”

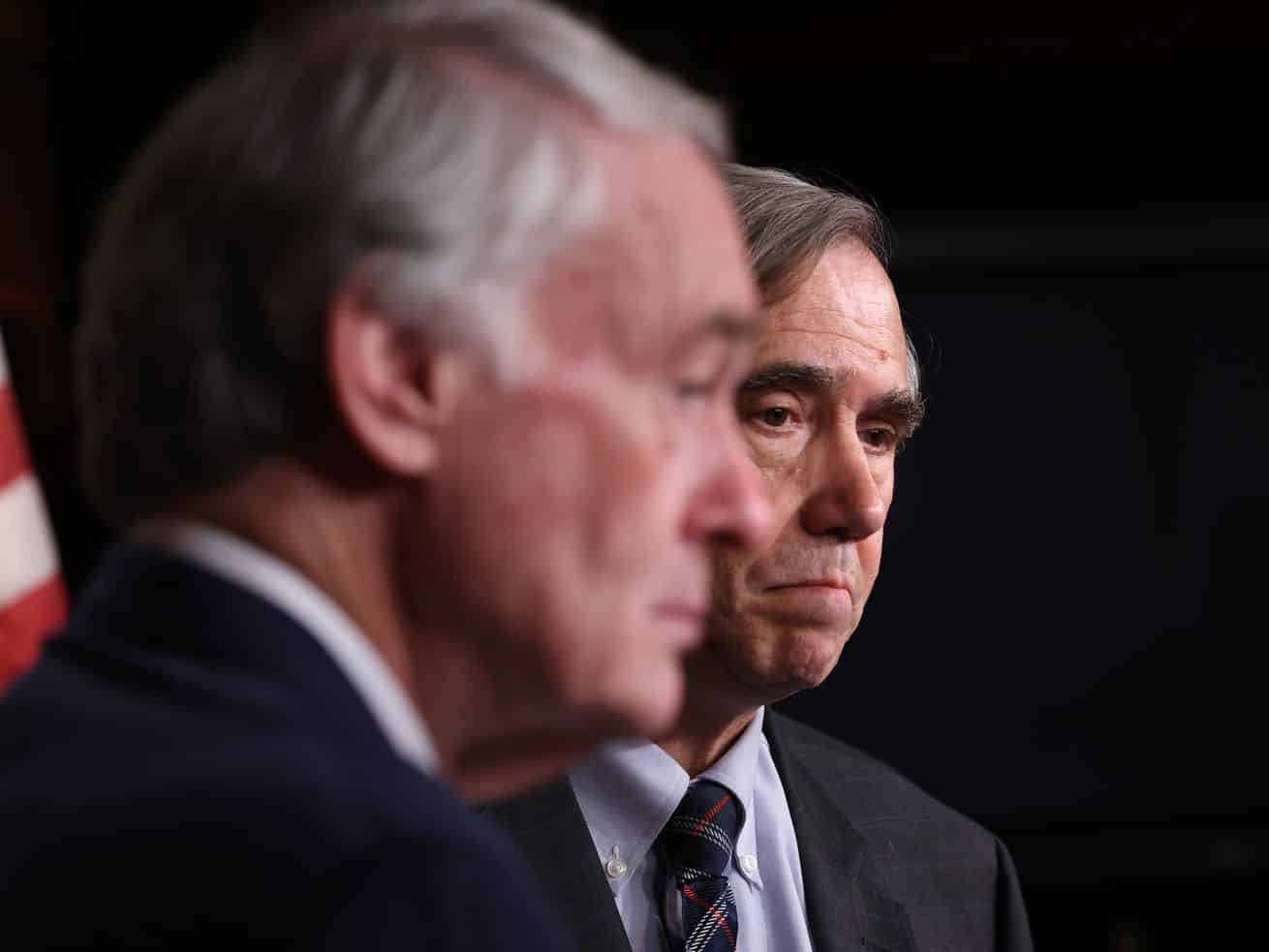

About a decade after his climate bill failed, Sen. Markey stood in front of reporters on June 15 and laid down a marker on the infrastructure bill President Biden’s administration is currently negotiating with Congress.

“If there is no climate, there is no deal,” Markey said. “There has to be an absolute unbreakable guarantee that climate has to be at the center of any infrastructure deal that we cut.”

There are scant details on what exactly is in a bipartisan infrastructure deal that has the support of 11 Republican and 10 Democratic senators. The bipartisan group is proposing $579 billion in new funding over five years, far less than Biden’s initial $2 trillion American Jobs Plan. But even as the White House continues negotiations, liberal senators are fuming that climate could once again be left out — or significantly diminished — in a final bill.

“While the nods to climate that are in the bipartisan bill are appreciated, they don’t even come close to putting us on a 1.5 [Celsius] degrees trajectory,” said Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse (D-RI), referring to the temperature limit of global warming the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change says will avoid the most severe climate impacts, including drastic melting of Arctic sea ice. Whitehouse has been very vocal about his concerns that climate could fall out of an infrastructure deal, tweeting in early June that he was “officially very anxious about climate legislation.”

“We have a planetary emergency that essentially anyone who’s not on the payroll of the fossil fuel industry agrees with,” Whitehouse told me. “Unfortunately, a lot of people around here are on that payroll, so this is the place where it’s difficult.”

The Rhode Island senator is one of a group of about a dozen senators — not including Democratic members of Congress — who have said they will withhold their votes for a bipartisan infrastructure package unless it includes sufficient spending on climate and clean energy.

“Fundamentally, this is the direction the world is going, the economy is going, and the world is going,” said Sen. Tina Smith (D-MN), who is leading an effort to get a clean electricity standard passed as part of an infrastructure bill. “The US can either choose to lead or we can follow.”

Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer vowed this month that he wouldn’t pass an infrastructure package that didn’t “reduce carbon pollution at the scale commensurate with the climate crisis.” Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-VT) and Schumer are charging ahead with a two-pronged strategy: A bipartisan infrastructure bill, and a budget reconciliation package that can be passed with Democrat-only votes, as long as Schumer can keep the caucus united. Sanders told reporters that package could be up to $6 trillion and is expected to contain spending on climate and Biden’s American Families Plan, which includes billions of proposed investment into child care and affordable education.

“There’s no reason to believe that any Republican would be strong on climate,” Sanders, who is the Senate Budget Committee chair, told me. “It has to be obviously in a reconciliation bill, it goes without saying.”

But it might not be that easy. Just relying on reconciliation could contain potential pitfalls; The Senate parliamentarian is charged with interpreting Senate rules, and given the purview to decide what can and cannot be passed using reconciliation. Some moderates are concerned that going it alone on an expensive climate bill will come back and hurt them in the 2022 midterms, which are already expected to be difficult for Democrats. Others fear that every month they spend on these prolonged bipartisan talks exacerbates the time crunch before the 2022 midterms and the risk that they won’t have time even for a one-party bill.

“We are concerned,” Sanders told me, adding that “not a day goes by without negotiations with the parliamentarian.”

What has changed since Waxman-Markey?

Talking to people who have seen decades go by in the Senate with little measurable action on climate, you get guarded optimism that things will be different this time.

For one thing, the impacts of climate change are inescapable in daily life. Those living along the Gulf Coast brace for hurricanes each summer. People living in New England may not have scorching summer temperatures and the forest fires of the West, but the scourge of ticks and Lyme disease and warming Atlantic Ocean temperatures are noticeable. And in the Midwest, it’s the flash floods and strong storms.

“You don’t even have to say ‘climate’ or ‘change,’ you just have to say ‘extreme rain events,’” said Baldwin, referencing storms in 2016 and 2018 that washed out roads. “These are supposedly 500-year events happening two years apart.”

The politics around climate change — and what to do about it — have changed significantly over the past decade.

With a data set they’ve been building for 13 years, researchers at Yale and George Mason universities used to see about 12 percent of people they classified as “alarmed” about climate and the same amount who were “dismissive” about the issue. Over the years, the numbers have shifted. Those in the alarmed group have grown to about 26 percent (there’s another 29 percent who classify themselves as “concerned” about climate change), while the number in the dismissive category has shrunk to 8 percent.

There’s also widespread support among voters for the US to embrace clean energy. In a December survey, Yale and George Mason researchers found that 66 percent of registered voters said developing sources of clean energy should be a “high” or “very high” priority for the president and Congress. That number was 13 percentage points higher than the number of registered voters who said global warming should be a high or very high priority for the president and Congress, the poll found. And 72 percent of registered voters supported transitioning the US economy from fossil fuels to 100 percent clean energy by 2050.

Business and industry are also embracing clean energy because it’s become even cheaper than fossil fuels — particularly wind-generated energy, the cost of which has fallen as much as 80 percent in the last 20 years. America’s car companies are phasing out gas-powered vehicles, promising to go all-electric within 10-15 years. Ford CEO Jim Farley recently said that demand for the company’s electric vehicles has been very high, and that the vast majority of their EV customers are new Ford consumers.

And finally, infrastructure — and possibly by extension, clean energy and investments in electric vehicles — is currently sitting at the top of Biden’s legislative priorities.

Republican attacks on climate policy and clean energy are also not as forceful, precisely because industry is starting to embrace it. The GOP is grappling with how to address climate, while also attacking Biden’s climate agenda as one that will kill jobs and deprive people of hamburgers.

“If you’re Kevin McCarthy, you really want the party to be relevant on climate change,” said former South Carolina Rep. Bob Inglis, now the executive director of Republican climate group RepublicEn. “He and others see the numbers, they see young conservatives want action on climate change just like young progressives want action on climate change.”

In a bid to win back suburban districts, McCarthy and House Republicans have released their own climate plan, which involves planting 1 trillion trees and beefing up funding for clean energy research and development. Inglis’s group is working to get the GOP to embrace a carbon tax, which could be easier said than done.

Podesta, Lawrence, and progressive lawmakers think Democrats may have a bigger problem on their hands if they can’t pass a big and bold climate bill, and warn that failing to motivate the base could result in lower Democratic turnout in the 2022 midterms — potentially handing control of Congress to Republicans.

“The Democrats are not going to be able to endure a disaffected base in 2022,” said Lawrence, Pelosi’s former chief of staff. Just like in 2009, House lawmakers still have to deal with “this great big wet blanket that’s the Senate that really squashes the legislation that passes the House,” he added.

If legislation stalls and Democrats lose the midterms, there could well be more years lost in the fight against climate change.

Author: Ella Nilsen

Read More