The antiwar movement died when Obama was elected. It could happen again.

Above is a picture of a young Honduran boy watching television, alone, in a caged immigration detention facility, supervised by a uniformed guard. The photo was taken in 2014, under the presidency of Barack Obama.

Now, this child was in all likelihood an unaccompanied minor who came to the border without a parent or guardian. Obama didn’t engage in the cruel family separations and needless criminal prosecutions that have characterized the Trump administration’s approach to border security. Acting as though Trump is simply continuing Obama’s policies, as far-right news outlets like Breitbart have, is seriously misleading and a mischaracterization of the rather huge changes that Trump has brought.

But it’s possible to err in the other direction too, to underrate the continuities between the two administrations’ immigration policies. There’s a reason why immigration advocates labeled Obama the “deporter-in-chief”: he really did deport more people than any other president before him. Early in his presidency, he ramped up enforcement as part of an ultimately failed strategy to win support for a pathway to citizenship. And while he prioritized removals at the border over internal raids by ICE, and sought to bias deportations toward criminals and away from law-abiding undocumented people, he oversaw the same brutal federal border patrol and immigration enforcement bureaucracy that Trump has used to such devastating effect.

Which is why I’ve watched the massive Democratic mobilization against Trump’s family separations with a mixture of admiration and unease. Admiration, because it’s the right thing to do, and signals that Democrats are not willing to respond to Trump the way that center-left leaders in other rich countries have responded to right-wing populists — by capitulating to demands for immigration restrictions in an attempt to court voters drawn to the new right’s brand of white backlash politics.

Maybe, unlike Obama, they won’t attempt a border crackdown once in power again in the vain hope of building bipartisan support for an immigration reform package. Maybe they’ll usher in a vastly more open immigration regime, one where deportation is anomalous, not routine, and where families fleeing violence receive asylum as a matter of course.

But I feel unease too, because maybe that’s not what the Democratic uproar signals at all. Maybe the family separation issue is a cudgel that’s useful for attacking the Trump administration, but which, as a principle, will be abandoned as soon as Democrats retake power in 2021, 2025, or beyond.

I don’t say that to draw an equivalence between the parties; we have every reason to expect that Democrats will adopt a more humane policy toward immigrants than Trump has. To some extent, from a voter’s perspective, that’s all that matters. I’m not making a “there’s actually zero difference between good and bad things” argument.

But we’ve seen this play before. As the political scientist Michael Heaney and sociologist Fabio Rojas document in their book Party in the Street, the main things that killed the antiwar movement in the US in the 2000s were Democratic victories in the 2006 midterms and the 2008 presidential election.

Once Democrats controlled Congress, and especially once they controlled the presidency, the energy and fervor behind ending the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq dissipated; Democratic partisans no longer had much interest in waging that fight when the political enemies were, increasingly, their own.

“We observe demobilization not in response to a policy victory, but in response to a party victory,” Heaney and Rojas write. “The rise of the antiwar movement as a mass movement can be traced to dissatisfaction among many Democratic partisans with the presidency of George W. Bush. Anti-Republican partisanship helped to fuel the growth of the antiwar movement and explains why its mobilization appears to have depended more on changes in partisan control than on substantive adjustments in foreign policies.”

You can tell a similar story about torture and waterboarding (which Obama largely ended but declined to prosecute), or about warrantless government surveillance, at least until the Edward Snowden revelations of 2013 forced the issue back into public consciousness. Those were issues that motivated passionate opposition to the Bush administration and mobilized Democratic partisans.

But when Obama offered legal impunity for torturers and continued warrantless surveillance apace, relatively little grassroots Democratic opposition emerged. Perhaps more importantly, the fact of that mobilization before his presidency did not prevent Obama from going light on torturers or continuing warrantless surveillance in the first place. He did not, of his own volition, hold himself to the policies of the anti-torture, anti-surveillance activists who helped him win the Democratic primary and ultimately the presidency.

So what happens under, say, President Joe Biden (or President Bernie Sanders or President Elizabeth Warren, etc. etc.) in 2021? They won’t separate kids at the border, for sure. But they’ll definitely deport people. They’ll likely use ICE to break up families and communities, just the same as Obama did. The path of least resistance will be to revert to standard immigration practices, no matter how inhumane those are. And a Democratic president could very well take that path.

Why this time could be different: Democrats are moving left on immigration

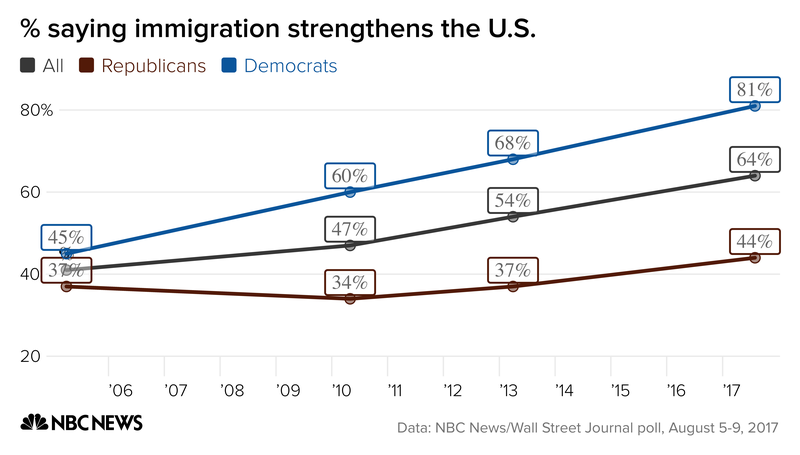

The case for optimism runs through public opinion — especially among Democrats. For the past few years, there’s been a steady trend of Americans becoming more supportive of immigration. An NBC poll last summer found that the share of Americans saying that immigration strengthens the US had grown from 47 percent in 2010 to 64 percent in 2017. Among Democrats, the share grew from 60 percent to 81 percent, from a majority view to an absolutely dominant one:

NBC News

NBC NewsPew Research Center has reached similar findings, and political scientists Daniel Hopkins (at the University of Pennsylvania) and Michael Tesler (at University of California Irvine) have found that the 2016 campaign made Americans more pro-immigration, including on Trump’s signature issue of a border wall.

So the best-case scenario is that this trend holds, pressure for immigration restrictionism dissipates, and pressure for more humane policies mounts, and the next Democratic president responds by ordering ICE and Customs and Border Protection to stand down, to detain fewer people, to conduct fewer internal workplace raids, and so forth.

If Democrats take Congress, too, they could make a pathway to citizenship a legislative priority — perhaps without the nods to border security and employer enforcement that past bipartisan efforts have included as a sop to restrictionists.

But the worst-case scenario is that Hopkins and Tesler are even more correct than they know, and that without Trump around, support for immigration dissipates, as supporters have no one against whom to react. Public opinion shifts back or stalls and Democrats, lacking the kind of grassroots mobilization we’re seeing right now, return to the safer-seeming approach of tough border security and calls for a legislative reform package.

I don’t know which path is likelier. But it feels all too possible that come 2021, Democratic elected officials and voters will forget the children at the border, just as they seemed to forget America’s wars come 2009. And if they do, today’s outrage will not have done the work it should, it must, do.

Read More

https://cdn.vox-cdn.com/community_logos/52517/voxv.png