The civil rights icon called for nonviolence but also warned about violent white mobs.

This year, America commemorates Martin Luther King Jr.’s life amid a chaotic and shameful time for democracy. Less than two weeks ago, insurrectionists stormed the United States Capitol after they were encouraged to “take back” the country by the sitting US president, holding fast to the false claim of election fraud.

During moments of social and political turmoil, we often ask ourselves, what would King do?

Unfortunately, the same forces that motivated the insurrectionists have tried their hardest to water down and whitewash King’s message and legacy. White supremacist ideology motivated the Capitol attack, and it’s this same power that has, in recent years, attempted to mischaracterize King’s words to fit their agenda.

Vice President Mike Pence, for example, has likened Donald Trump to King in an effort to defend Trump’s border wall. “One of my favorite quotes from Dr. King was, ‘Now is the time to make real the promises of democracy,’” Pence said on Face the Nation ahead of MLK Day in 2019. “You think of how he changed America. He inspired us to change through the legislative process, to become a more perfect union.’”

Other Trump administration officials have done the same over the last four years.

On MLK Day last year, then-press secretary Sarah Sanders tweeted, “Today we honor a great American who gave his life to right the wrong of racial inequality. Our country is better thanks to his inspiration and sacrifice,” failing to recognize that King was assassinated at the young age of 39. King did not give his life to white supremacy; white supremacy took it. Sanders’s statement also failed to acknowledge how King’s death set off riots across the country and effectively undermined the civil rights movement that King helped lead.

He was assassinated Sarah https://t.co/SZ14TXQqGq

— Mary Wilson (@TheeMaryWilson) January 21, 2019

Even the National Rifle Association seized on King’s legacy, twisting the circumstances of his death to fit their gun rights agenda. The organization tweeted last year, “King applied for a concealed carry permit in a ‘may issue’ state and was denied. We will never stop fighting for every law-abiding citizen’s right to self-defense.” The organization suggested that had King not been denied a right to carry a weapon, he might have survived his assassination. They, too, neglected to mention that he was murdered by a white escaped felon who managed to access firearms despite restrictions.

This year, those seeking to uphold the hate and bigotry that King vehemently fought against will surely try their hand at rewriting King’s story once again, calling for peace and unity in the wake of a riot that sought to overthrow democracy and roll back justice. And America has to see it for what it is: an attack that King would have unequivocally denounced.

“King’s image and tactics are misappropriated and intentionally mischaracterized by those who would be squarely within his focus as an enemy to democratic ideals and the ideals of equality and fairness in this country,” Janai Nelson, associate director-counsel of the NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund, told Vox. “What we should be remembering about King is that he was in no way, shape, or form a pacifist. He believed in nonviolence. He believed in a tradition of sustained protests. And he also believed in full truth and transparency about the evils of white supremacy.”

King can’t solely be defined by pacifism or by confrontational action

King’s radicalism, his decision to love Black people and fight for their humanity, is on full display in his “Letter From a Birmingham Jail,” in which he addressed his fellow clergymen who deemed his strategies and tactics extreme. In the letter, he acknowledged the violence of white supremacy and why urgency was the only option.

“Perhaps it is easy for those who have never felt the stinging darts of segregation to say, ‘Wait.’ But when you have seen vicious mobs lynch your mothers and fathers at will and drown your sisters and brothers at whim; when you have seen hate filled policemen curse, kick and even kill your black brothers and sisters […] then you will understand why we find it difficult to wait.”

And his acknowledgment of white violence was not confined to extremists. He also noted the violence of white moderates who threatened the fight for civil liberties. According to King, they were the greatest threat to Black advancement.

[…] I must confess that over the past few years I have been gravely disappointed with the white moderate. I have almost reached the regrettable conclusion that the Negro’s great stumbling block in his stride toward freedom is not the White Citizens’ Councilor or the Ku Klux Klanner, but the white moderate, who is more devoted to “order” than to justice; who prefers a negative peace which is the absence of tension to a positive peace which is the presence of justice; who constantly says: “I agree with you in the goal you seek, but I cannot agree with your methods of direct action”; who paternalistically believes he can set the timetable for another man’s freedom; who lives by a mythical concept of time and who constantly advises the Negro to wait for a “more convenient season.”

As if foreshadowing how politicians would use his name to promote their own agendas, King called out moderates whose answers to racial tensions were not to engage with what justice would look like, but instead simply call for peace. He acknowledged that white moderates had no interest in seeing Black people gain freedoms and didn’t care to join in the fight for policies that would bring about real change.

King’s legacy was also not just confined to justice on the basis of racial categorization; it includes his fight against capitalism (he was working on the Poor People’s Campaign in the months before he was assassinated and was in Memphis to support a sanitation workers’ strike), the Vietnam War (he condemned the war in a 1967 speech called “Beyond Vietnam”), and limited citizenship for the oppressed (during his tour of Europe in 1964 on his way to accept the Nobel Peace Prize in Oslo, King celebrated social-democratic governments).

King told his wife in a letter in 1952, “I imagine you already know that I am much more socialistic in my economic theory than capitalistic … [Capitalism] started out with a noble and high motive … but like most human systems it fell victim to the very thing it was revolting against. So today capitalism has out-lived its usefulness.”

America has also attempted to elevate King’s “I Have a Dream” speech as the key address that defined him, the address in which King supposedly advocated for seeing character over color. While King did indeed say that people should be judged by the content of their character and not by the color of their skin, he never claimed that seeing race itself was the problem. In the same address, he was clear about how the construct of race played out for Black Americans:

“But one hundred years later [after the Emancipation Proclamation] the life of the Negro is still sadly crippled by the manacles of segregation and the chains of discrimination; one hundred years later the Negro lives on a lonely island of poverty in the midst of a vast ocean of material prosperity; one hundred years later, the Negro is still languished in the corners of American society and finds himself an exile in his own land.”

King would have turned 91 this year, a year that has already seen efforts to undo the principles he espoused. In a year when insurrectionists want to reaffirm white supremacy, it’s important to see King’s legacy for what it truly was: complex. He called for nonviolence, but he also demanded unrest until there was no injustice anywhere.

“We must honor MLK by honoring him,” author and historian Carol Anderson told Vox. “We honor him by not hijacking his words and twisting them to fit a white supremacist agenda.”

According to Anderson, American leaders often recite how we should be a country that judges people by the content of their character, but their pleas aren’t genuine. “We have policies that in fact don’t care about character but go after the color of people’s skin,” she said. “So until we have a system that recognizes that, don’t spout the words of Martin Luther King to advance or to provide a fig leaf to cover the white supremacist agenda.”

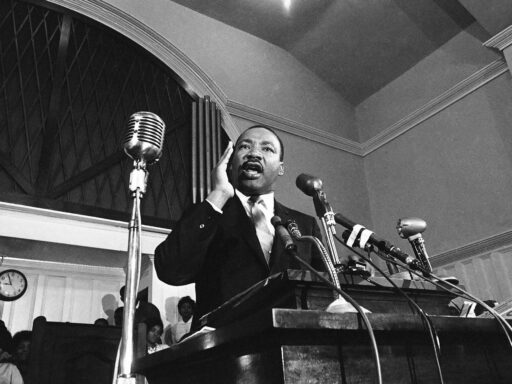

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22241712/AP_358654533368.jpg) AP

APIt’s going to require some work to truly live up to the vision that King had for the world, Anderson said. That involves knowing our real history, whites having real conversations with other whites, and dismantling the kinds of reflexive responses America has to white supremacy.

For Nelson, honoring King’s legacy means outright demanding accountability for white supremacy.

“To allow January 6 to occur without any consequences is to set us back and undo the work and the sacrifice of Martin Luther King Jr. and those that he stood up for. It would be one of the deepest assaults against his legacy,” Nelson told Vox. “And we will not sit idly by while this entrenched minority of radical domestic terrorists and extremists attempt to undo that incredibly important work.”

As for what King would have said in this moment — in witnessing a president supporting white supremacists and trying to overturn an election — his words have always been with us. In his last book, Where Do We Go From Here, King wrote: “White Americans must recognize that justice for black people cannot be achieved without radical changes in the structure of our society. The comfortable, entrenched, the privileged cannot continue to tremble at the prospect of change of the status quo.”

Author: Fabiola Cineas

Read More