Mass shootings are a serious problem. But we shouldn’t let fear of them take over our lives.

This piece is an argument that our societal panic over mass shootings is taking on alarming proportions. Before you close the tab, let me be very clear: Mass shootings are a serious problem, and gun control would help reduce them.

I have written, by my count, at least 21 articles on gun violence during my time at Vox, most of them arguing strenuously for additional restrictions, including a large-scale confiscation of semiautomatic weapons. I have been especially vocal in trying to spread the compelling evidence that gun restrictions reduce suicides, which make up the majority of gun deaths in the United States. This is a problem that I take seriously, and that I wish our political system took more seriously.

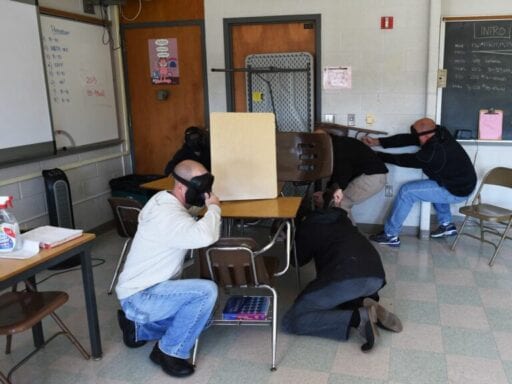

At the same time, I have had multiple friends talk to me about their fear of public spaces in the wake of mass shootings; one mentioned it as a potential reason to leave the United States. I once talked to an elementary school teacher who said she had to deal with parents terrified their children could be next. I know parents whose kids are sent into active shooter training at ever-younger ages and who end up being traumatized by those trainings. (Vox Media itself is coincidentally holding two active shooter trainings this week, though, sensibly, they’re just presentations without the traumatizing “drill” aspect.)

Those are anecdotes, but survey data bears out the point. A poll last month from the American Psychological Association found that a third of adults say they feel they “cannot go anywhere without worrying about being a victim of a mass shooting,” and the same share say they avoid certain places for this reason. A quarter of respondents report changing their behavior in an attempt to avoid shootings. A USA Today/Ipsos poll released around the same time found 21 percent of respondents say they’ve skipped events to avoid mass shootings. Older polls from Gallup find about 40 percent of Americans report being scared of being the victim of a mass shooting.

I understand these reactions. Mass shootings are terrifying. They make us feel vulnerable in normal spaces, and make the world around us feel alarmingly dangerous. I do not blame anyone for feeling scared.

But I think the fear of mass shootings risks becoming a public panic out of proportion to the actual danger being faced. We have an epidemic of gun deaths in America. Mass shootings are a problem, but the fact remains that they account for only a very small share of gun deaths annually. And as horrific as each mass shooting is, it’s still a fairly rare event in American life — as rare as lightning strikes.

Their reality should not prevent you from going out in public, from sending your kid to school, from living your life. We have to learn to hold these thoughts — the horror of mass shootings, and their statistical rarity — in our heads simultaneously.

The terrorism panic and the mass shootings panic

The panic over mass shootings is a panic of a kind I recognize from the early 2000s, in the wake of 9/11, and continuing through the war on terror. There, the ideological stakes were reversed: Pro-war conservatives and liberal hawks tried to argue that terrorist attacks are important despite their rarity, and liberals (including President Obama) and libertarians liked to remind people that you were likelier to die in the bathtub than via a terrorist attack — not to minimize the tragedy of terrorism deaths, but to attempt to put them in proper context.

Fears over terrorism seeped into normal life. People were afraid enough to fly in the wake of 9/11 that some researchers have argued thousands of additional people died or were injured in car accidents, because they drove instead of flew. I remember letters to the editor in my small New Hampshire town fretting about inadequate preparation for a terrorist strike — as though any al-Qaeda member thought that Hanover, New Hampshire, was really the heart of the empire that their organization needed to target.

On that issue, I sided strongly with John Mueller and other analysts who argued the risk was overblown. Yes, terrorism is a fat-tailed problem, whose biggest costs come from rare and impossible-to-predict exceptions to the tranquil norm, but even the death toll of such attacks pales in comparison to other fat-tailed problems like nuclear war between great powers, pandemic disease, and climate change. Low-frequency, relatively low-casualty events didn’t seem to deserve the billions the federal government was throwing at them, and the fear and security theater the public was forced to endure. (We still take our shoes off at the airport, as though that does anything.)

But the risk of being killed in a mass shooting is also smaller than or similar to your risk of being struck by lightning. Definitions of “mass shooting” differ, but between 85 and 373 people died in such incidents in 2018. Lightning deaths are extremely rare (20 in 2018), but there are about 400 lightning injuries a year.

Are mass shootings becoming more common? Possibly — but it’s a small increase in a small risk. They do appear to be becoming more deadly when they do appear. But again, the absolute risk that a given person will fall victim remains very low. Moreover, it’s easier to present the rates of shooting as increasing if you use a more restrictive definition of mass shootings; it’s harder to show an increase with a more expansive definition. If mass shootings are increasing, that could be because we’re defining them in such a way as to paint them as a smaller problem to begin with.

This no more means that we should not care about mass shootings than it means that we should not care about lightning strike deaths (which are plummeting due in part to a public education campaign). A premature death is a premature death. They are all bad.

But the logic of Mueller and others’ effort to remind Americans of the rarity of terrorist strikes wasn’t to diminish the tragedy of deaths from terrorism. It was twofold: to push back at what they saw as a wasteful and unnecessary policy agenda justified as a way to prevent terrorism, and to assuage public fears that they could be the next person al-Qaeda kills.

The case for and against raising the profile of mass shootings

When it comes to gun control, I don’t share Mueller’s first worry, of bad policy gone amok. Indeed, for years, writers like me have used mass shootings as a news peg to talk about gun control policy and gun violence more broadly — especially gun suicides, by far the biggest cause of deaths by guns.

For some time now, however, I have sat with growing unease at the readiness with which we execute that pivot. The reason we switch to talking about suicides is obvious: Mass shootings kill a few hundred Americans per year, whereas 23,854 people died by gun suicide in 2017. And unless they’re a celebrity, none of those 23,854 people’s deaths make national headlines. Mass shootings, however, do — they are shocking and public and trigger a sense of fear that gun suicides do not, at least in non-suicidal people.

Talking about gun suicides in the wake of mass shootings was a way to expand readers’ sense of what the problem was, to take the attention raised by the mass shootings and attempt to use it to expand the circle of empathy to encompass people whose suicides could’ve been prevented if they didn’t have access to guns. The policies that could prevent more mass shootings — mandatory gun licensing, extreme risk protection order laws, and the like — would also make a dent in our gun suicides problem. It was a sensible connection to draw.

But I have grown progressively more uneasy about this argumentative slide from mass shootings to suicide, for a couple of reasons. The first is that raising the profile of mass shootings is dangerous for reasons having little or nothing to do with gun control. There is some evidence that mass shootings produce a copycat effect: Mass shootings are more common in the weeks immediately following a previous mass shooting than at other times.

That suggests that by allowing coverage to feed the impression that mass shootings are very common, journalists like me might indirectly be giving potential shooters inspiration. The degree to which that is our responsibility as reporters — whether we have a duty to downplay these events that outweighs our duty to report them as news — is a fair topic of debate. But it’s a possibility that should disturb anyone in the media who covers these stories, and one that many outlets, like the gun-focused publication the Trace, have grappled with at length.

The second cause of unease is the non-gun control policies that a fixation on mass shootings enables. Take active shooter drills. Such drills have no rigorous evidence base behind them. I could find no randomized evaluations suggesting that they actually reduce casualties in a subsequent mass shooting — and indeed, that kind of evaluation would be incredibly hard to pull off given how rare mass shootings are compared to how common active shooter drills are.

A number of researchers think active shooter drills could actually be harmful. I spoke to Jillian Peterson, a professor of criminology at Hamline University who has extensively studied mass shootings and has conducted one of the only rigorous studies on active shooter trainings to date. That study found that while showing a training tape to community college students increased their feelings of preparedness compared to a control group shown a video without active shooter training elements, it also increased fear and anxiety (particularly among female students) and led them to increase their estimate of how common mass shootings are. More anecdotal journalistic accounts draw similar conclusions.

Beyond the risk of trauma, Peterson worries the drills can actually help perpetrators. In school shootings specifically, the perpetrator is almost always a fellow student. “That means that the perpetrator has been running through the drills themselves and we’ve seen perpetrators use that knowledge to increase casualties,” Peterson told me.

Less scientifically, Peterson’s personal experiences give her cause for worry. “I was talking to my second-grader the other day about the lockdown drill at school, and he was saying he had to sit in the middle of the carpet. I was like, ‘Why do you sit in the middle of the carpet?’ And he said, ‘You want to be away from the windows, just in case the bullets go through the windows,’” she recalls. “And he just said it like it was absolutely nothing. Like this was just part of going to school, knowing where to sit in case bullets come flying through their windows.”

Now, it’s possible to take concerns like Peterson’s too far. I grew up in the wake of Columbine and the Oregon mass shooting in 1998; I remember lockdown drills, and I suspect the vast majority of millennials who went through that experience did not emerge from it majorly scarred.

A concern can stop short of panic, however, and I think what we know about shooter contagion and about the psychological and practical costs of active shooter drills merit concern. Combined with the lack of evidence supporting those drills’ effectiveness, the case for this kind of tactical escalation in response to rare events like mass shootings strikes me as incredibly weak.

There are other ways we can tackle the problem of mass shootings. Peterson argues that we can and should be doing more to look out for warning signs. She notes that in the vast majority of shootings she’s studied, the perpetrators plan to die themselves; in the vast majority of shootings, the perpetrators also leave notes outlining their plans.

Using notes as a warning sign raises a fair concern over false positives: Most people who leave notes don’t carry out mass shootings, even if most people who carry out mass shootings leave notes. But we can approach those notes the way we approach warning signs for suicide. You don’t need to be entirely confident a friend is going to die by suicide to intervene; that presents far too high a bar.

Similarly, Peterson says, a medical rather than police intervention for troubled young people who plan mass shootings could prove effective without devolving into Minority Report-esque surveillance efforts to predict shootings before they happen. “We’ve done a lot of work on suicide prevention and what it looks like to stop the contagion,” she explains. “I think that a lot of those strategies could be implemented” for mass shooters as well.

A humanistic approach to preventing these shootings could steer us away from the kind of societal panic that leaves ordinary people wondering if it’s safe to go to the mall. We can take mass shootings seriously without overreacting, and we can prevent them without resorting to anxiety-inducing, unproven tactics like active shooter drills. And yes, we should continue the push to pass meaningful gun control laws.

“Don’t let the terrorists win” was a catchphrase to the point of being a punchline in the years after 9/11. We should consider not letting the mass shooters win as well — by not letting them condemn us to a permanent state of fear.

Sign up for the Future Perfect newsletter. Twice a week, you’ll get a roundup of ideas and solutions for tackling our biggest challenges: improving public health, decreasing human and animal suffering, easing catastrophic risks, and — to put it simply — getting better at doing good.

Author: Dylan Matthews

Read More