It’s okay to be okay during the coronavirus crisis.

We’re all struggling, to some degree, to adjust to life during the novel coronavirus pandemic. But some are struggling far more than others. People who have contracted Covid-19, who have lost loved ones to the disease, who are working on the front lines to keep others healthy, who don’t have enough food or a safe place to live — these are people who are bearing the brunt of the suffering right now.

If you’re not one of these people, you may feel a great deal of gratitude — and maybe a bit of guilt. It can feel uncomfortable, even shameful, to be enjoying good takeout and fun TV shows under a cozy blanket in a nice home when you know millions of others are experiencing the greatest hardship of their lives.

The trouble with guilt is that it’s often counterproductive. It can make us feel overwhelmed and paralyzed. In that state, it’s hard for us to actually help anybody. We’re not able to be useful to other people or reduce their suffering, because we ourselves are suffering from an emotion that we’ve allowed to ensnare us.

Perhaps there’s comfort in remembering that we’re not the first human beings to grapple with this problem. Many thinkers have contemplated it over the millennia and left us with rich wisdom and traditions to help us navigate it. As I’ve spoken to mindfulness teachers during the pandemic, there’s one Buddhist teaching I’ve found particularly helpful. It’s found in a discourse called the Sallatha Sutta, also known as “The Arrow.” Maybe you’ll find it helpful, too.

The Buddha taught that when we experience something painful — a physical illness, or the news that someone we love has died, or witnessing suffering all around us — it’s as if the world has shot an arrow into us. It hurts! That pain is totally normal, and it’s fine to acknowledge it. In fact, it’s good to acknowledge it, to let ourselves simply be with the experience of pain.

But often, what we then do is shoot a second arrow into ourselves. That second arrow is any thought we use to spin up a “story” around our pain, as a way of resisting simply being with the experience of pain. This can manifest in many different ways.

It can take the form of shame: “I’m such a weak person, to be crying out like this!” Or anger: “How dare the doctors not save my loved one’s life! They’re so incompetent!” Or ruminating: “If only I’d nudged my loved one to take this or that extra precaution, maybe they wouldn’t have died.” Or catastrophizing: “I’m going to die, too!” Or guilt: “I don’t deserve to live while other people are dying.”

We’ve all got our second arrow of choice. Whichever one you incline toward, the key thing to bear in mind is that it’s self-inflicted, which is to say, it’s optional. It might not seem that way, because it comes upon you so quickly that it seems automatic, but the Buddhist teaching insists this is a second arrow we shoot into ourselves. And doing so is what causes us suffering. As many Buddhist mindfulness teachers like to say: Suffering = Pain x Resistance.

The Buddha, in the Sallatha Sutta, teaches that there’s another way.

The well-instructed disciple of the noble ones, when touched with a feeling of pain, does not sorrow, grieve, or lament, does not beat his breast or become distraught. So he feels one pain: physical, but not mental. Just as if they were to shoot a man with an arrow and, right afterward, did not shoot him with another one, so that he would feel the pain of only one arrow. … As he is touched by that painful feeling, he is not resistant.

In other words, if we can be brave enough to sit with the original painful feeling (the first arrow) even though that feels hard and scary, we can avoid spinning up a narrative around that feeling that will cause us to suffer (the second arrow). Unburdened by guilt, we can be more productive and proactive and actually be effective actors in trying to ease suffering. Taking care of our own emotions can make us better at helping others.

How to apply this Buddhist teaching during the pandemic

It’s one thing to understand a teaching intellectually, quite another to know how to apply it. To help us understand how we can actually use the teaching of the second arrow in our current moment, I called up Rhonda Magee, a mindfulness teacher with a focus on social and racial justice.

“This teaching is part of the core curriculum of traditional Buddhism,” she said. “It isn’t a program for how to transcend difficulty. It’s a program for how to be more and more open to the vast amount of difficulty that can show up in life … and engage more skillfully with all that.”

When I asked what I should do if I’m feeling guilt — for example, after reading that Covid-19 is disproportionately taking black lives — she recommended using a practice called RAIN, which has been popularized by contemporary meditation teachers like Tara Brach. The acronym stands for recognize, allow, investigate, nurture. Here’s how Magee suggested moving through the process.

Recognize that a first arrow has hit you — a piece of news has caused you pain — and, if possible, just sit with that rather than immediately shooting yourself with the second arrow of guilt. If you’re already feeling guilt, recognize it’s arisen in reaction to this piece of news.

Accept what is happening. Let yourself fully feel in the body what sensations and emotions are arising when you receive that piece of news. Notice them and name them, without getting caught up in them.

Then investigate the emotions. “Unpack the guilt,” Magee said. “Guilt in and of itself isn’t a bad thing. The question to look at is: Is this neurotic guilt, where it’s not really about something I’ve done, but I’m taking on more than my appropriate share of responsibility? Or is this feeling of guilt [arising because] I’m living in a way that’s not aligned with my values? Have I personally acted in a way that misses my own ethical mark? Is this trying to tell me something I need to know about how I’ve structured my life?”

Magee also noted that sometimes wallowing in guilt is a way of letting ourselves off the hook. “If I say, ‘Oh, I’m so privileged, but there’s nothing I can do about it because it’s systemic’ — is that me avoiding having to do something different and take action?” It’s worth investigating that, too.

Finally, you want to nurture yourself, maybe by journaling, calling a friend, or saying something soothing to yourself. Then, crucially, you also want to nurture others. That could mean contacting a mutual aid group to ask about volunteer opportunities or making a donation to an effective charity or working with your community to get good officials elected.

“Try to take some action, without getting attached to the outcome,” Magee said. “Take mindfulness from being just a personal liberation practice to [being about] how we might minimize the arrows that are hitting the more vulnerable because of the ways we’ve structured our society.”

Bottom line: If you’re doing fine during the pandemic, there’s no sense in wallowing in guilt over it. Your guilt doesn’t actually help anyone; it just adds more suffering to the world. Instead, you can see it as an indication that you’re well-resourced enough to be able to give more to others — and then go do that.

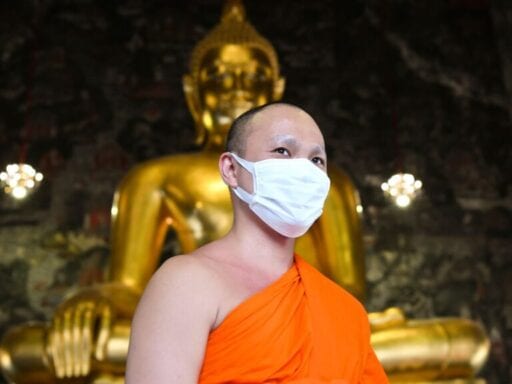

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19936241/monks_middle_way_GettyImages_1208739664.jpg) Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe art of suffering with others: Becoming a bodhisattva and following the Middle Way

There’s something comforting about knowing that people have grappled with the same questions we’re facing — whether and how to suffer with others — for millennia and have left us their best wisdom.

The Mahayana branch of Buddhism, which has a rich tradition of thinking through these questions, includes the notion of a bodhisattva: a person who’s able to attain enlightenment but who holds off on it because they want to help other beings who are still suffering.

Any one of us has the potential to become a bodhisattva, but it requires a lot of compassion and selflessness. You have to be willing to postpone your own ultimate well-being, your own nirvana, in order to help others along the path to their well-being.

“We have to ask ourselves: Are we willing to suffer a bit more?” Magee told me. “We are being willing to suffer with others, to a degree, in those moments when we extend ourselves with compassion.”

Note that the point here is not that we should unthinkingly let ourselves get caught up in second-arrow suffering, which we inflict upon ourselves but which doesn’t actually help anybody. As mentioned above, that’s just adding more suffering to the world, which is counterproductive. Instead, the idea is that we can make a mindful choice to hold off on some of our own gratification in service of helping many others suffer less.

But there’s a trap here we’ve got to watch out for. “If you’re constantly trying to become a bodhisattva, that’s clinging to another story,” Magee warned. In other words, if you’re dead-set on the goal of rescuing all other beings, you’re spinning up a narrative and becoming attached to a certain idea of yourself — you’re making the self the object of what you’re trying to do. This might even lead you to do damage: You may feel like you need to give away everything you’ve got to those who are less fortunate until you yourself become ill.

The Buddhist teaching of the Middle Way cautions against this showy breed of asceticism. It insists that we should avoid the extremes of both self-denial and self-indulgence.

“That teaching is there to help us be a human being doing the best we can to confront suffering we see,” Magee said, “while knowing that there’s a temptation to come up with a new story of ‘No, but you need to do more! If you really want to help, why are you stopping there? Do more!’”

At the end of the day, she said, we need to find balance: helping ourselves while also helping others. Neither is good without the other. In fact, knowing how to do the former can make us better at the latter.

As Magee put it, “Taking care of ourselves is the first approximation of mindful compassion.”

Support Vox’s explanatory journalism

Every day at Vox, we aim to answer your most important questions and provide you, and our audience around the world, with information that has the power to save lives. Our mission has never been more vital than it is in this moment: to empower you through understanding. Vox’s work is reaching more people than ever, but our distinctive brand of explanatory journalism takes resources — particularly during a pandemic and an economic downturn. Your financial contribution will not constitute a donation, but it will enable our staff to continue to offer free articles, videos, and podcasts at the quality and volume that this moment requires. Please consider making a contribution to Vox today.

Author: Sigal Samuel

Read More