Three years after Colin Kaepernick’s protests, the sport hasn’t changed. Neither have fans.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/15986155/Vox_The_Highlight_Logo_wide.jpg)

For longtime observers of American sports culture, week three of the NFL’s 2017 season unfolded in dizzying, unprecedented fashion.

It began in London, where Ravens and Jaguars players locked arms or dropped to their knees as the US national anthem reverberated across the Wembley Stadium international game site. The protest movement quickly crossed the Atlantic and cascaded across time zones, from an anthem singer in Detroit genuflecting during the song’s final notes to the majority of Raiders players stationing themselves on the bench to the Seahawks and Titans not even bothering to come out of their locker rooms in Nashville. By day’s end, hundreds of NFLers, team after team, black and white players alike, took part in the civil disobedience over injustice leveled at people of color.

“Nothing, literally nothing, in the history of sports and politics can compare to what happened [that] Sunday,” marveled the Nation’s Dave Zirin, perhaps the foremost chronicler of sports and politics.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19300361/GettyImages_852940540.jpg) Simon Cooper/PA Images via Getty Images

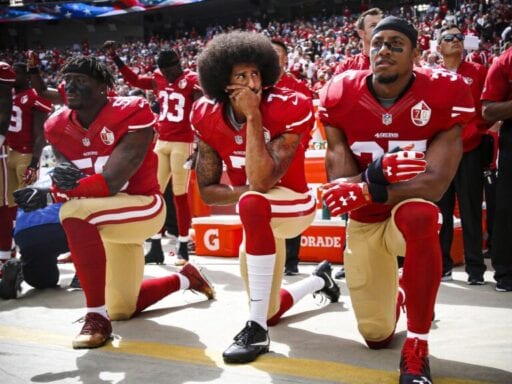

Simon Cooper/PA Images via Getty ImagesA year earlier, then-San Francisco 49er quarterback Colin Kaepernick began the protests by kneeling during the national anthem. But that week, President Donald Trump conjured his swaggering Apprentice-era catchphrase at a pep rally and goaded just about half the league into Kaepernick’s corner: “Wouldn’t you love to see one of these NFL owners,” Trump said, “when somebody disrespects our flag, to say, ‘Get that son of a bitch off the field, right now, out? He’s fired.’”

The American sports world changed forever. And as this season heats up, it has become apparent: It has slowly but surely changed back.

Football players (and NBA general managers, but that’s another story) seem to be “sticking to sports” a bit more this season. And our research shows that fans would, indeed, generally prefer it that way.

According to a national survey of 1,051 Americans I conducted with political scientist Emily Thorson in November 2016 to understand fan attitudes about sports and politics, about half of all Americans believe the two “should not mix,” while only 1 in 5 approved when they did. (The remainder of respondents expressed no inclination.) Self-identifying conservatives opposed sports’ politicization even more strongly than their moderate and liberal counterparts — no doubt primed by Kaepernick and others’ protests, which were taking place during the survey’s circulation.

Yet an intriguing follow-up question persisted in the wake of declining TV ratings, flat merchandise sales, advertiser anxiety, and outraged front-yard immolations of jerseys and Nikes: Why, exactly, do overt politics so miff sports fans?

Digging into the open-ended responses to our survey, we arrived at several conclusions. Foremost, fans seem to harbor the impression that athletes wield dangerous influence over other gullible fans; in this reading, Kaepernick and his conspirators are powerful Pied Pipers hoodwinking credulous audiences down a political path.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19304378/GettyImages_838053294.jpg) Drew Angerer/Getty Images

Drew Angerer/Getty ImagesFans also object to — in their words — “overpaid” “dumb jocks” straying too far from their lane. They see athletes as uninformed on the issues, unappreciative of their own financial good fortune, and uncommitted to the single-minded focus demanded within professional sports.

One respondent drew this out through an ironic analogy: “Everyone has their opinion, but just as it wouldn’t be appropriate for a police officer to start rambling on about a politician during a traffic stop, pro athletes are doing [their] job and don’t need to use their fame to promote or put down a candidate.”

If some of this sounds like coded doublespeak for racial attitudes, the suspicion is not unwarranted. Just as black athletes have, historically, been slighted with lay theorizing about genetic privilege (e.g., “naturally” gifted, unlike their scrappy, hustling, white counterparts), so, too, have they been insulted with softly bigoted low expectations around intellect, temperament, and leadership capacity.

The very success that affords high-profile African American players the visibility of their national platform to protest injustice is turned against them and used to “prove” that impediments to inequality are a thing of the past. If you’ve found fame and fortune — so goes the thinking — you’re delegitimized as a potential critic of “the system” because you represent living, breathing evidence of its fairness, especially in a refuge like sport that prizes meritocratic mythologies above all.

Like fans, sponsors also wanted no business (sometimes literally) with activist athletes; historically, brands have been incentivized against entering any partisan fray. As Tony Ponturo, former head of sports marketing for Anheuser-Busch — possibly the most powerful patron of the industry — observed: “If [sponsors] pay a lot of money, and all they’ve done is walk into someone else’s dialogue of potential negativity, then they’re going to start saying, ‘Why am I paying millions of dollars for this controversy?’” After all, they’re really only there to sell beer.

Athletes internalize that logic effortlessly; they’re long since accustomed to thinking and acting like human “brands.” And, thus, we’re more or less back to normal at this point in terms of “sticking to sports.”

But because the memory of that disruption remains powerful, the protests have, in the past year, been retrofitted into sports’ classic hero narrative: You can still sell shoes and tickets with a vaguely “woke” aura but without necessarily explicitly taking a knee. Kaepernick can’t find back-up work but confidentially settled a collusion grievance with the league and converted his ostracism into a commercially inspiring message for Nike.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19304400/GettyImages_1029312412.jpg) Angela Weiss/AFP/Getty Images

Angela Weiss/AFP/Getty ImagesThe NFL, meanwhile, announced it would be earmarking a nine-figure sum toward social justice issues and partnered with Jay-Z to be the hip face of that effort. Ratings have rebounded this season, just like the last (though this is partly comparative, since television otherwise continues to be a vast wasteland of fragmenting, cord-cutting, vanishing audiences).

The great irony, however, is that even if “woke” politics, in their explicit form, have been deftly exorcised from the sports landscape, two other issues that have defined and divided America this century persist there, less obviously and yet more enduringly: economic inequality at home and military intervention abroad.

What on earth do sports have to do with wealth distribution? They rationalize it, ideologically, perhaps better than any other entertainment form. They tell us, over and over again, that the world is a level playing field and that anybody can get ahead with a little pluck and hard work. They provide our culture’s most persuasive script for what I call “capitalist catechism”: narrating that the source of success is not some preexisting privilege of genetic blessings or Steinbrennerian spendthrift.

Whenever we celebrate the superstar baller who has hustled out of poverty or swoon for a 16-seed David slaying Goliath, we’re championing the “self-made” hero who pulled themselves up by their own Air Jordans. We’re also affirming the righteous reality of the Protestant sports ethic and American meritocracy: People fail because they’re lazy, and they win because they just want it more than the next competitor.

Those messages matter at a time when the top 1 percent retain a greater share of the nation’s wealth than the bottom 90 percent and CEOs reap 300 times the salary of their average employee. Public opinion appears to reflect this: In our survey, we found that, compared to non-fans, sports fans are more likely to believe that financial outcomes reflect meritocratic practices and that hard work and ambition determine whether people get ahead more than growing up with wealth, connections, and superior schools. The bootstraps, sport tells us, are right there for the taking.

Speaking of bootstraps, for decades — and certainly since 9/11 — teams and leagues haven’t “stuck to sports” but have rather camouflaged themselves in hawkish propaganda. From enlistment inductions to surprise homecomings to gratitude for the troops on the Jumbotron screen, two Republican senators exposed how much of this patriotism was paid for, costing the Pentagon millions of dollars in line items.

Here, too, our study showed that sports fans have distinct political leanings: They’re more likely than non-fans to support increased defense spending. Sports offers “guerrilla marketing” to a $700 billion military industrial complex.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19304435/GettyImages_1181857679.jpg) Dustin Bradford/Getty Images

Dustin Bradford/Getty ImagesTo be certain, when people talk about politics intruding upon sports and dividing fans, these are not the usual politics they’re talking about. But I would argue that sports inform our attitudes about wealth disparity and endless warfare as much as they do racial discrimination and policing practice. Colin Kaepernick — along with the Miami Heat, Derrick Rose, the St. Louis Rams, and University of Missouri football players — have sought to keep fans “woke” about the latter, to the chagrin of most.

Michael Serazio is an associate professor of communication at Boston College and the author of, most recently, The Power of Sports: Media and Spectacle in American Culture.

Author: Michael Serazio

Read More