Covid-19 has led more states to adopt mail-in voting. But the method adds yet another barrier to ballot access in a hugely important election year.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/15986155/Vox_The_Highlight_Logo_wide.jpg)

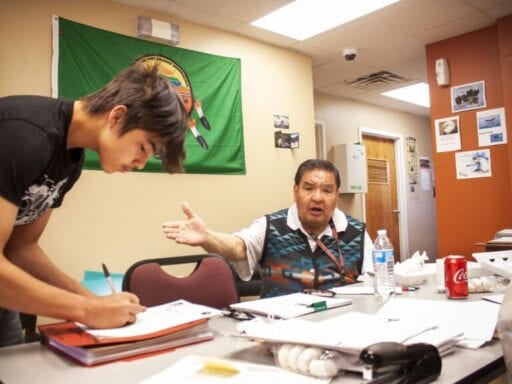

When election season rolls around every two years, the approximately 2,400 eligible voters living in the Fort Belknap Indian Community in Montana’s central plains start getting a lot of phone calls. Gerald “Bear Shirt” Stiffarm is often the voice on the other end of the line.

Fort Belknap sits on roughly 1,000 square miles; its vast grasslands, where buffalo graze, and its dramatic mountain buttes make up about 25 percent of Blaine County. The main road is a two-lane highway that snakes through the rolling hills. Two Native American tribes, the Gros Ventre and the Assiniboine, call this land home.

Stiffarm, 71, occupies two roles on the reservation: He’s the station manager at Native public broadcasting station KGVA in the small town of Harlem, and one of the founding members of the Snake Butte Voter Coalition, a nonpartisan group that has been mobilizing Native voters on the reservation to cast their ballots since the early 1990s.

It’s a Herculean task. “We call these people nonstop,” Stiffarm said in a recent phone interview. “We’ve heard every conceivable excuse there is for people not wanting to vote. They say, ‘Nobody cares about me.’ Well, we care about you.”

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/20030021/Gerald_Stiffarm.jpg)

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/20030025/DoyleSign.jpg)

When Covid-19 hit, Montana gave its counties the option to switch to mail-in ballots for the June 2 primary — and all of them did. Instead of in-person voting on Election Day, voters could drop their ballot in the mail or vote early in person at each county’s election office. But some satellite voting offices on Indian reservations like Fort Belknap also closed, leaving just one satellite office open in Blaine County for the primary, said county clerk and recorder Tammy Williams.

The satellite offices were the result of a 2012 lawsuit brought by three Native tribes to expand voting access on the reservations. In the last few election cycles, advocates say the offices helped increase Native American turnout across the state. During the 2018 midterm elections, Blaine County’s voter turnout was 71 percent — on par with the county record of 72 percent in the 2016 presidential election, according to the local paper.

The Covid-related closures were a setback that required some Fort Belknap voters to travel nearly 80 miles into town to collect and drop off their ballots, then 80 miles back.

While Montana as a state saw record primary turnout on June 2 — more than 389,000 ballots cast, compared with 293,000 in the 2016 primary, according to Montana Public Radio — the three counties with the lowest turnout were all home to Native American tribes including the Crow, Northern Cheyenne, Fort Peck, and Blackfeet. In Blaine County, primary turnout was just 46 percent, compared with 72 to 76 percent in some majority-white counties, according to the Montana Secretary of State’s office. (Williams said she doesn’t currently know whether one or both voting offices will reopen for the November general election, when turnout will surely be higher.)

As the novel coronavirus threatens the safety of in-person voting in 2020, voting by mail is on the rise. But this year’s primary turnout in Blaine County illustrates how it poses a predicament for Native American voters across the US: A voting method that’s supposed to be easier and more convenient adds yet another impediment to Native ballot access.

“You might as well say we are no longer citizens and can no longer vote,” said OJ Semans, a member of the Rosebud Sioux Tribe in South Dakota and co-founder of the Native voting rights group Four Directions.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/20030040/AP_19226813476382.jpg) Kali Robinson/AP

Kali Robinson/APThere are roughly 2.4 million eligible American Indian and Alaska Native voters living in the top 15 states with the highest populations of voting-age Natives, according to data from the National Congress of American Indians. Depending on how widespread and flexible mail-in voting is in the November presidential election, it has the potential to dampen turnout among those voters.

The problems related to mail-in voting are myriad for Native communities, advocates say. A lack of reliable mail access and a proliferation of nontraditional addresses on reservations, including those in North and South Dakota as well as the southwestern Navajo Nation, make home delivery impossible for many. For those with cars, simply visiting a post office to pick up and drop off a ballot can mean driving many miles on unpaved roads.

Mail-in ballots written in English are indecipherable to voters who don’t speak it, including older Navajo speakers, or Yupik speakers in Alaska’s Native villages who rely on translators at the polls. And if a voter is able to get a ballot and mail it in, there’s still the chance that a local election official could toss it because of something like missing information or a signature that doesn’t match the one on file. (Recent studies found that local election officials in Georgia and Florida were far more likely to reject ballots from minority and younger voters in the 2018 midterms.)

All of this, plus a long history of voter discrimination across the country, has contributed to Native American mistrust of voting by mail and a preference for casting in-person ballots, said Jean Schroedel, a political science professor at Claremont Graduate College and an expert on Native American voting rights.

While the practice has expanded overall turnout in states such as Oregon and Washington, which have had universal vote-by-mail elections for years, it doesn’t necessarily expand turnout among voters in minority groups such as African Americans and Native Americans, many of whom prefer in-person voting.

Access to voting was hard-won for Native communities, the result of years of lawsuits filed across the country. And vote-by-mail, activists and attorneys say, threatens to undo generations of work to increase voter participation on reservations.

“Vote-by-mail works really well for middle- and upper-class white folks,” said Schroedel. “It doesn’t work for other populations, and it really, really does not work for Native people living on reservations.”

A rapid shift to vote-by-mail

More states — red and blue alike — are making the switch or expanding their vote-by-mail capacity due to the threat of Covid-19. And congressional Democrats want more funding to help states develop no-excuse absentee vote-by-mail systems, as well as expand early in-person voting at polling locations.

“Vote-by-mail is perfectly fine voter reform. It’s great as part of a package of voter-friendly reform to get more people access to the ballot,” said Claremont Graduate College researcher Joe Dietrich, who works on Schroedel’s team. “The problem starts to arise when you make [it] the only option to get people the ballot.”

While Native American voting rights historically haven’t gotten much national attention, Native voters make up an important bloc in states like Montana and Arizona — two states with key 2020 races that could help determine the balance of power in the US Senate. In the 2018 Montana Senate race, only about 18,000 votes separated Sen. Jon Tester (D) and his Republican challenger Matt Rosendale. But Native turnout soared by 19 points that year, helping Tester win reelection while other Democratic Senate candidates came up short in Trump-supporting states.

“Democrats are never going to win in Montana with more than [a 3- to 4-point] margin,” a Democratic operative who was granted anonymity to speak freely told Vox. “The difference when you have high turnout in the Native community and you convince them to vote for you — that’s the difference between winning and losing.”

Even a few thousand votes make a difference. The sheer size of the Fort Belknap area means that shutting down satellite offices on the southern part of the reservation seriously disadvantages about 1,000 voters, Stiffarm estimated.

“We river rats on the north end, we get access to walk across the street and submit our ballot,” Stiffarm said. “The people on the south end, they’re called brush cats. They live in the mountains; they’re not as outgoing or gregarious as us.”

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/20030046/HaysNorth.jpg)

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/20030068/WilliamMain.jpg)

William “Snuffy” Main, a Gros Ventre tribal member in Fort Belknap, was part of the effort to put satellite offices in Montana.

“I’ve seen a lot of instances in the past, with our tribal elections, people have said they mailed their ballots in but their name was not on the list as having voted,” Main said.

As Stiffarm made his calls ahead of the June 2 primary, he discovered that voters who lived farther from town and had their satellite location shut down were less likely to want to vote.

“You have one voter going 78 miles one way. So guess what? They’re not interested in it,” he said.

With so much ground to cover in a rural area, Stiffarm and his volunteers typically rely on a sprawling family network in the tribes to get out the vote, starting with the grandparents on down to their children and their children’s children.

“We contact strategic elders,” Stiffarm said. “They become like ambassadors for us. Each election, it means more to them to say, ‘Yeah, those voter people called me, and yeah, I got all my kids to vote.’”

Family connections and traditions are an integral part of voting in Fort Belknap. Because Native Americans fought so hard for their right to vote, the act of voting is cherished and celebrated in the community — a rite passed down from generation to generation. The importance of casting a ballot was instilled in Main early by his father, who worked as a miner in Butte, as well as his grandfather, a Gros Ventre tribal elder.

When she was still alive, Main’s mother voted in every election, even after her polling place was moved from 5 miles away to 18. Just a few weeks ago, Main took his son — the youngest of his seven children — down to the remaining satellite office in Harlem to register and vote in the state’s primary. But Main has no desire to put his own ballot in the mail.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/20030017/Snuffy_sMom.jpg)

“A lot of Indians do not trust mail,” he said. “I don’t know if it’s something in my mind, I’d rather see my ballot dropped in the ballot box or run through the machine.”

“I don’t trust machines either,” he added.

“The tyranny of distance”

Voting by mail doesn’t necessarily solve a longstanding access barrier that one attorney referred to as “the tyranny of distance.”

Approximately one-third of all Native Americans, or about 1.7 million out of 5.3 million people, live on what the Census designates as “hard to count” tracts of land. The Southwestern Navajo Nation, for instance, is 27,000 square miles spread out over Arizona, Utah, and New Mexico. In Alaska’s remote Native villages, planes are the only mode of transportation to the outside world; that is, as long as the weather is good and the villages aren’t socked in with fog.

“Indian country is rife with what are called nontraditional mailing addresses,” said attorney Jim Tucker, who has represented Alaskan Native villages in lawsuits against the state. Traditional GPS doesn’t work on many reservations; it takes detailed directions from someone who knows the area to get to a destination.

Distance is one thing, but it’s coupled with high rates of poverty on reservations. About 26 percent of American Indian and Alaska Native people were living in poverty in 2016, compared to 14 percent for the US as a whole, according to the US Census. For families living on tight budgets, voting can be an expensive proposition.

“We’d call them up and say, ‘We want you to go vote.’ And we know in that home they may have to decide if they’re going to use their gas to get groceries or they’re going to go vote,” said Blaine County Commission Chair Dolores Plumage, the first Native American and the first woman elected to the county commission.

For Native communities across the country, the issues are similar. If a PO box is located 50 miles away, and a voter doesn’t have reliable access to a car or gas, they’re certainly not going to check it every day. The vast majority of roads on the Navajo Nation are not paved; if there’s a rainstorm and a road washes out, they’re stuck. In Montana, winter snowstorms in November have blocked reservation roads and required snow plows to clear a path to the polls. Post office boxes on reservations aren’t necessarily open five days a week, and many have limited hours. Many families share the office boxes.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/20030107/GettyImages_1215979958.jpg) Mark Ralston/AFP via Getty Images

Mark Ralston/AFP via Getty Images“We often had a shared box,” said Darrell Marks, a Navajo Nation member and local educator who grew up in Tonalea, Arizona. “I have three older siblings, and when they were off in their own home, they would still have mail sent to my mother’s mailbox.”

Tonalea is tiny town of less than 600 people located east of the Grand Canyon’s North Rim. It sits in a vast sandy and scrubby desert on the Navajo Nation; its most prominent landmarks are two massive sandstone pillars called Elephant’s Feet.

When Marks votes in Arizona’s elections, it’s as easy as walking to the mailbox in front of his Flagstaff house and dropping in his absentee ballot. But when it’s his mother’s turn, just getting her mail-in ballot requires a 200-mile roundtrip drive from her main residence in Flagstaff to the post office box she keeps in Tonalea, where she still maintains a part-time residence on her tribe’s homeland.

“Voting is still something she is very much committed to,” Marks said. But keeping one foot on the reservation, where fixed addresses aren’t always a given, and mail delivery is spotty, bears incredible significance to her, too. “There’s something about maintaining consistency or having a permanent address that has a lot of value to my mother and her generation.”

If it’s tough for a person to even get their ballot through the mail, the travel time for that ballot is similarly long and complex. With limited capacity and an inability to date-stamp mail at some of the smaller post offices, a piece of mail often is routed through major cities such as Salt Lake City, Utah, or Phoenix, Arizona, before reaching its final destination.

“That’s how the postal system works, and that’s a challenge for citizens on the Navajo Nation,” said Leonard Gorman, executive director of the Navajo Nation Human Rights Commission. “This is not an issue about ‘You’re not smart enough.’ This is a system that was instituted several decades ago that really hasn’t changed as much as it should to accommodate, for example, voting activities.”

Another massive barrier to voting by mail is language. For tribal elders on the Navajo Nation and in Alaskan Native villages who don’t speak English, reading a ballot in English without translation services is impossible. The state’s response was to blame the tribes for, as the state characterized it, not informing officials about the language-translation issues.

“It’s like if I handed you a ballot in Russian and said, ‘Vote on this.’ You’re not going to understand what you’re doing,” said Tucker. Polling places are legally required to provide translation services; getting the state of Alaska to comply with the necessary translation services spelled out in the Voting Rights Act has not been easy, however. It’s involved multiple lawsuits.

Some congressional Democrats who have been some of the loudest advocates for putting vote-by-mail in place in every state before the November election concede that it doesn’t work for everyone. Many believe there should be a safe, early voting option at physical locations for those who prefer it, with adequate protective equipment for poll workers.

“I think the answer is, this is not simply a hard one-size-fits-all,” Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-MA), an advocate for vote-by-mail, told Vox. “It’s a recognition that we start with the presumption that everyone is going to get a ballot by mail, and in circumstances where that’s particularly challenging, like with people living on reservation land, that we adjust the rules so they will be able to get their ballots and return their ballots easily.”

Advocates in Montana and Arizona say the solutions should include plenty of time for early, in-person voting on the reservations in addition to voting by mail. They say there should be outreach and voter education and postage provided, so no extra cost is imposed on voters. And in Montana, a judge recently sided with the ACLU and NARF in a lawsuit to allow local voting rights groups to pick up ballots of voters who live far away from post offices or polling locations.

“If we were able to collect ballots, those people who wanted to vote would not have obstacles to voting,” said Marci McLean, executive director of Montana-based Native voting rights group Western Native Voice. “I think we could drastically improve turnout in our communities.”

Years of disenfranchisement and mistrust

In 1924, the US Congress passed the Indian Citizenship Act, granting citizenship for Native Americans. But the law left it up to the states to decide whether to grant Native Americans the right to vote, and it would take nearly four more decades for all states to do so; Utah was the last in 1962. When Native Americans started voting and running for office, white election officials were not always friendly.

“Because we were not considered property owners, we should not have the right to vote,” was the message telegraphed to Natives in Montana in the late 1970s, Plumage recalled. As recently as 2018, Native Americans testified at field hearings held by Tucker and fellow attorney Jacqueline De León that they experienced racism from local white election authorities who suggested that they shouldn’t be able to run for office because they didn’t pay taxes (tribes do, in fact, pay taxes to the federal government).

Voting disenfranchisement for Native Americans has moved from the outright denial in the 1950s and 1960s, before the landmark 1965 Voting Rights Act, to other, more subtle ways that voting access has been made difficult. Before Montana’s satellite offices were set up, Fort Belknap tribal members said, they’d show up to their designated polling place to vote, only to find local election officials informing them they had to go elsewhere.

“The locations often were changed on us. At times, I had to go drive off the reservation to a location to go vote,” Main said. “A lot of people got annoyed and didn’t vote.”

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/20030109/GailMain2.jpg)

In 2012, Montana Native American tribes sued then-Secretary of State Linda McCulloch, alleging that sites for in-person late registration and early voting in Blaine, Big Horn, and Rosebud counties discriminated against them because they were located in the county seat — often far away from the reservation. A brief filed by the US Department of Justice at the time cited research calculating the disparity in distance for whites and American Indians in each county. The disparity was greatest in Blaine County, where the mean distance to the county courthouse for voting-age residents was about 10 miles for white residents, compared with 31 miles for Natives.

In 2013, Shelby v. Holder gutted a key part of the Voting Rights Act by striking down a provision requiring jurisdictions to “preclear” any upcoming election rule changes with the federal government before putting them into place. Now, Native Americans often have just one remedy to expand their voting access: suing.

When Alaskan Natives fought for the ability to have an early voting period in their villages, the state Department of Elections sent just 25 to 50 ballots to areas that had hundreds of voters and said that it was enough.

Problems have persisted. Attorneys told Vox that as recently as 2016, one local election official in Alaska kept more than 100 Native voters from being registered, refusing to send more than 25 registration applications per village because, the official said, they didn’t think the Native villagers would fill out the forms.

“When we called and asked about that, [the official] said [Native voters] really aren’t interested in voting, and if we send 150 registrations, we’re only going to get a handful of them back,” said Natalie Landreth, an Alaska-based staff attorney at the Native American Rights Fund. “We see that all over the place, these local, county-level decisions that will have huge impact on registrations, ballot access. A lot of those decisions aren’t set in statute.”

Native tribes have had some success to get the same basic rights afforded to other Americans, but these suits can drag on for years and drain tribes of their financial resources. Whereas tribes have to foot their bills, state and local governments have more resources through municipal insurance and aren’t on the hook for court fees.

And it can often feel like re-litigating matters already written into law. “We’re letting the courts decide who has rights and who doesn’t have rights,” Dietrich said.

Unsurprisingly, years of lawsuits also breed mistrust and animosity between tribes and predominantly white governments at every level — local, state, and federal.

“You’re going to have significant trust issues, and why would someone vote in an election where they don’t trust their vote is going to count?” Dietrich added.

In Montana at least, Native Americans are making progress at the local and state level. The percentage of Native American legislators in the state legislature (7.3 percent) is slightly higher than the percentage of Native American in the state’s population (6.7 percent). Despite the effect of vote-by-mail on turnout in counties with large Native populations in June, 15 Native candidates won their primaries and will compete in the general election, including in the state auditor’s race.

While there’s still plenty of lingering mistrust of the federal government and the predominantly white officials who currently run it, advocates and local officials say the only way to increase that trust is to get Native American voters to elect more of their own to positions of power. To do it, access to ballots, polling places and translation services will be key.

“I think people are realizing if we’re not engaged, our issues will go under addressed or un-addressed,” McLean said. “We need to make our own seat at the table, because they’re not going to make it for us.”

Ella Nilsen is a politics reporter at Vox who covers the 2020 elections and Congress. Her last piece for the Highlight chronicled the rise of youth climate group the Sunrise Movement.

Terri Long Fox is a photographer based in Billings, Montana.

Support Vox’s explanatory journalism

Every day at Vox, we aim to answer your most important questions and provide you, and our audience around the world, with information that has the power to save lives. Our mission has never been more vital than it is in this moment: to empower you through understanding. Vox’s work is reaching more people than ever, but our distinctive brand of explanatory journalism takes resources — particularly during a pandemic and an economic downturn. Your financial contribution will not constitute a donation, but it will enable our staff to continue to offer free articles, videos, and podcasts at the quality and volume that this moment requires. Please consider making a contribution to Vox today.

Author: Ella Nilsen

Read More