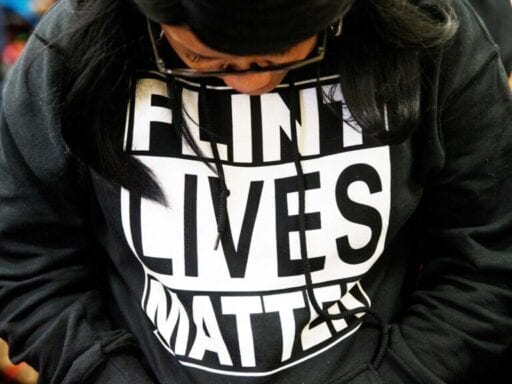

The coronavirus outbreak is an added public health threat in Flint, a community that still struggles with clean water and resources.

A full day before President Donald Trump declared the coronavirus outbreak a national emergency, the mayor of Flint, Michigan, declared a state of emergency. Mayor Sheldon Neely could see what was coming. The community has been living in crisis since the city started taking water from the Flint River in 2014, flowing it through corrosive pipes and into homes for drinking even though it was tainted and lead-ridden.

With the coronavirus pandemic sweeping across the country, the newly elected mayor knew it would only be a matter of time before Flint was dealing with an added health crisis. He would be proactive rather than reactive, he decided, for the majority-African-American community.

“It’s just such a crisis on top of a crisis with a side of crisis,” he told Vox by phone. “So we’re engaging on every level.”

A week before declaring a state of emergency on March 12, the mayor put forth a new 14-day quarantine policy for those returning from travel. The day after the declaration, he limited public gatherings to 30 people. Four days later, he shut down city hall. Before the week was over, he issued a stay-at-home-order. As of Thursday, more than 60 people have tested positive in Genesee County where Flint is, according to the state’s count, and a woman in a homeless shelter in the city has tested positive for the virus.

The mayor’s swift actions were necessary in a community as vulnerable as Flint’s: Forty percent of its 95,000 residents live below the poverty line, with nearly two-thirds of its children living in poverty, deepening the void between residents and access to regular health care, food, and clean drinking water. So while coronavirus fears sweep the nation, unlike the Americans who have the time and resources to stockpile toilet paper, Clorox wipes, and pasta, residents of Flint are already lagging.

“Your health care depends on who you are,” a 2014 Robert Wood Johnson Foundation report begins, citing disparities in coverage based on race and ethnicity, while a 2017 Health and Human Services finding ends with: “The death rate for African Americans is generally higher than whites for heart diseases, stroke, cancer, asthma, influenza and pneumonia, diabetes, HIV/AIDS, and homicide.” African Americans are also 4 percent more likely than their white counterparts to be uninsured and 7 percent more likely to fall into a coverage gap, a 2019 Kaiser Health News report found.

Citing these concerns, a group of black doctors told BuzzFeed’s Nidhi Prakash earlier this week they were calling on both the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the World Health Organization (WHO) to reveal if black communities across America were at a disadvantage in receiving coronavirus tests. Neither the CDC nor the Johns Hopkins data — which consists of CDC, WHO, and other resources — break down positive coronavirus cases by race or ethnicity.

While there may not be much national data regarding race, the coronavirus numbers coming out of Detroit, one of the blackest and poorest cities in the nation, proves how much the virus impacts low-income communities of color. Just two weeks ago, there was not a single coronavirus case reported in the city, and now there are more than 850 cases and 15 related deaths, according to the state government’s numbers. With a large number of residents not only living in poverty but also with acute health issues like diabetes, Detroit’s numbers are accelerating, Bridge Magazine reported — well beyond the state level in a state with one of the worst public health systems in the country.

“When you have undervalued communities, black and brown, by the majority of our society, we have to have an extra push, that extra fight to make sure that people are getting [their] fair share of the resources and supplies as necessary to safeguard life,” Neely said.

Many of these black communities are staring down poverty, making the burden of a pandemic too much for many people

For years, Catherine Flowers, the rural development manager for the Equal Justice Initiative, has visited Lowndes County in Alabama. Lowndes has a 75 percent black population. It does not have access to a basic municipal sewage system and its residents have contracted hookworm, an intestinal parasite often exacerbated by poor access to clean water. To divide the county even further, 37 percent of African American residents live below the poverty line compared to 4 percent of white residents.

Many of those people in Lowndes County, Flowers points out, are still working hourly jobs during the coronavirus pandemic because they do not have the economic privilege of working from home, or not working at all. Many are working retail jobs, she said, and some of those jobs don’t have workers’ protections while also having the highest level of exposure to the coronavirus. Social distancing is not possible for people who need money for their next meal.

Only in recent days, Montgomery and Birmingham, two of the states’ urban cities, rolled out coronavirus tests, she pointed out, so it would be highly unlikely the tests would make it to a county of 10,000 people.

“I’m also concerned about the lack of testing in a lot of these areas, especially the rural areas, so we really won’t know the extent of their illnesses,” Flowers told Vox. “And my question is, if someone died of cardiac failure in these rural communities, and they have not been tested, we will not get a true understanding of what caused it.”

On top of that, cellphone connection and internet is spotty in Lowndes and many people do not have access to accurate, timely information. Inaccurate rumors were flying about the coronavirus, she said, with some suggesting black people couldn’t catch the virus.

“I think that some people believe that, and it did mean that they didn’t protect themselves early enough,” Flowers added.

Meanwhile, in urban cities like Detroit, as the number of cases jumps closer to New York’s numbers per capita, the city’s mayor promised 400 tests would be available to residents each day, six days a week, for the next six weeks, Bridge Magazine reported. However, with more than 25 percent of the city’s population working in the service industry, and even more in the gig economy, residents might not have the choice to social distance for the next month as they need to go to work or pick up side work.

Reverend William Barber II, a board member of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People and a leader of the Poor People’s Campaign, says the magnitude of the pandemic only exacerbates the fissures of equality in society. He has spent much of his career in low-income communities of color, including Lowndes County and counties in Louisiana, Mississippi, West Virginia, and North Carolina. Both the reverend and Flowers agree it is not just race playing a factor in the lack of preparation and ability to access health care: Income inequality further exacerbates these communities’ efforts.

“Prior to this virus, 140 million people were poor and low-income. Well, that’s 43 percent of your country. In the midst of this virus, the very thing that we are asking people to do we are often saying to them from a position of wealth and not understanding that because we didn’t address poverty,” Reverend Barber said. While social distancing works for those who have the privilege of working from home and ordering groceries, for some, social distancing for even one day can affect if they eat for a whole week or a whole month, he explained.

Making physicians and health centers available to these communities is a solution, the American Medical Association’s first African American president Dr. Patrice Harris told Vox. But at the same time, it should not be the responsibility of any one clinic or organization to reach these under-resourced communities, she said. “This needs to be an item of discussion and thoughts about how to make sure that there’s access to qualified health centers.”

Dr. Harris also points to the $2.2 trillion dollar stimulus package and the conversation around making health care available to those who might lose their jobs. The bill offers $150 billion in emergency aid to state and local governments with the premise it be used for coronavirus.

“I think states could do this, regarding Medicaid and work with the federal government, figuring out a way to make sure that folks who either lost their [health care] or now will be even more vulnerable would have access to test Medicaid.”

Coronavirus tests should also remain free and available to everyone, Dr. Harris said. But that has also been a painfully slow process across the country in both urban and rural populations as hospitals reach their capacity with patients requiring tests and care.

A local solution to a constant local burden

As they wait for aid, more resources for hospitals and doctors, and the effects of the stimulus package, those manning distribution centers in Flint or volunteering near food banks in Lowndes are stepping up.

Mayor Neely, ahead in his emergency declaration, took charge of the looming coronavirus crisis coming toward Flint. Four months into his new role, he ordered water disconnected by the previous administration reconnected. Greater Holy Temple church, one of the three distribution centers in the city, is taking on the burden of passing out food and water to city residents, witnessing earlier and longer lines for bottled water while other cities across the country shelter in place and practice social distancing.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19854429/GettyImages_516164180.jpg) Brett Carlsen/Getty Images

Brett Carlsen/Getty ImagesFlowers, in Alabama, says most residents in Lowndes and other areas like it will rely on dwindling supplies at food banks, hoping they do not have to go to the doctor for a flare-up of their diabetes or heart issues.

Like many officials, General Russel Honore, who led Task Force Katrina after the devastating hurricane destroyed New Orleans, says most of these communities — whether in Alabama, Michigan, or Louisiana — will see catastrophe because the federal government is managing a crisis engulfing the entire country and won’t be able to get to those who can’t take care of themselves: “The ones who do not have a cushion in the budget to buy extra food to stay home, those who have to pay for electricity when they have no money, or to pay for gas to get to work.”

But he says he’s seeing local and state officials in Baton Rouge, for example, try to ensure people stay home. “Kids that are out of school in the poor communities have access to food through the [schools] placing food in their [neighborhoods],” he said. “The governor has put together a plan to have the National Guard post food in communities. And if people have food, they’re more likely to stay home.”

On Facebook, people are organizing ways to drop food off for those who need it, he said. The general calls it innovative. “But,” he warned, “it’s going to get worse before it gets better. We haven’t seen the real test yet.”

Author: Khushbu Shah

Read More