Was Friends homophobic and way too white? Yes. But arguing about the show is healthy.

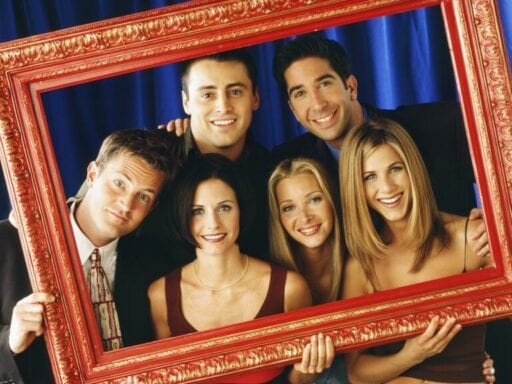

This month marks the 25th anniversary of the premiere of Friends. You may have heard about this, oh, everywhere. Everyone loves a pop-culture anniversary, but this particular milestone is being celebrated with everything from a pop-up “experience” in New York City to Pottery Barn and Ralph Lauren collections to light shows on the Empire State Building — and the obligatory onslaught of Friends retrospectives and think pieces from every extant media outlet and publisher. Twenty-five years after its debut, there’s still plenty to say about Friends — and to critique, or downright trash.

Full disclosure: I actually wrote one of those many retrospectives, a whole book on the history and legacy of Friends. One thing that became abundantly clear in my research is that most people — even those who didn’t really watch it — seem to have an opinion on the show. And unlike other popular television series, this one seems to have a particularly divisive effect: People either fall into the camp of “Friends is hateful garbage and should be canceled,” or “Friends is perfect and untouchable and if you say anything bad about it, then you should be canceled.” My favorite headline from the latter camp is this one from the Telegraph: “If Friends falls victim to the new cultural revolution, nothing is safe.”

Forget The Rachel haircut; I think Friends’ ability to polarize is the show’s true legacy. It has become a way for us to look at (and argue about) enormous societal issues — racism, misogyny, homophobia — through the lens of a sitcom.

Diehards like to wave away its flaws in one fell swoop simply by calling it a product of its time. And it is! Friends has come to represent everything that was great and shitty about the ‘90s: a time before social media, reality TV, and the reality TV president. A time before 9/11. Also a time before marriage equality and transgender rights. A time when an all-white New York City was not just plausible on television, but expected.

The capital-I issues with Friends can’t be summed up in a hot take, but that doesn’t mean they’re not worth examining. So, take a deep breath and let’s break down the five most glaring issues with one of television’s most problematic faves.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19216509/138414665.jpg.jpg) NBC/NBCU Photo Bank via Getty Images

NBC/NBCU Photo Bank via Getty ImagesIs Friends homophobic?

In short: Yep. It’s riddled with lazy gay jokes, which was standard for sitcoms of its era. But the homophobia on Friends is also more complex than that. It is truly a Don’t Ask Don’t Tell-era show, full of small steps forward and anxious jumps back.

This tension is perfectly exemplified in season two’s The One With the Lesbian Wedding, an episode that’s equal parts envelope-pushing and full of gay panic. Ross’s ex-wife Carol marries her longtime girlfriend, Susan. Ross has a hard time accepting this, which sucks, but is relatable; he expresses these feelings by drawing on his bottomless supply of lesbian jokes, which just sucks.

On the envelope-pushing side, you’ve got two women walking down the aisle and pledging vows to one another. Their not-yet-legal union is officiated by Candace Gingrich, the LGBTQ rights activist and sibling of Newt Gingrich (who when the episode aired in 1996 was one of the most visible anti-gay politicians in power). Carol and Susan even have queer icon Lea DeLaria as a wedding guest!

On the gay panic side, everything else about the wedding is carefully curated to be as cautious and heteronormative as possible: The brides are walked down the aisle by men, wearing long, pastel gowns — a decision made by costume designer Debra McGuire, who later explained: “I really loved the idea of these women being women, of them looking beautiful and feminine, because of the stereotypes about gay women.”

The implication was that women in pants aren’t real women, but an ugly stereotype that needs to be corrected. DeLaria herself balked at this overt erasure of very real women like her: “They needed at least thirty or forty more fat dykes in tuxedos. All those thin, perfectly coiffed girls in Laura Ashley prints — what kind of lesbian wedding is that? And no one played softball afterward?”

Another thing obviously missing from this wedding? A kiss. The actresses did lobby for one, feeling that going without would be a very odd omission, but producers nixed it, fearing an audience backlash.

It wouldn’t have been a first. Though Ellen DeGeneres’s coming out was still a year away, gay unions and kisses weren’t unheard of: Fox sitcom Roc depicted a same-sex wedding in 1991 (albeit also without a kiss). Roseanne had shown the first kiss between women (in an episode actually titled “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell) in 1994 — though it was played for a big laugh, rather than a sincere, romantic moment.

In the end, The One With the Lesbian Wedding was removed from the air by two local affiliates (in Texas and Ohio), but did not create the waves that both producers and network executives feared. After hiring a slew of temp workers to answer the expected flood of angry calls, NBC received two. The episode was one of the highest-rated in the entire series. In other words, there was no need for so much hand-wringing.

The One With the Lesbian Wedding certainly set a precedent for other shows to follow, and to push the envelope further. Looking back, perhaps the most insidious homophobia on Friends is its desire to make the homophobes in its audience more comfortable.

Where are all the people of color?

Good question. The answer throughout much of Friends’ run was: primarily on UPN. There were black shows and there were “mainstream” shows — which explains the Manhattan of Friends, exclusively populated by Caucasians and one Asian woman named Julie.

Those who roll their eyes at criticisms of the show tend to argue that any recent hubbub is just 21st-century PC culture run amok. But the truth is that critics raised this issue with Friends from the beginning — and from the beginning, the cast and creators were defensive about it, arguing that they were being unfairly dinged because their show was so popular.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19216543/143479671.jpg.jpg) NBC/NBCU Photo Bank via Getty Images

NBC/NBCU Photo Bank via Getty ImagesDuring season one, the cast was featured in a Rolling Stone cover story — a legendary piece that helped launch the buzzy new series into a phenomenon. David Schwimmer spoke of “the race issue” on behalf of the whole group: “Listen, the fact is that we could be more diverse…But it doesn’t necessarily bother me. You can’t do everything to please everybody, and I know that in casting, they did look at all sorts of different people. This just happens to be the group they ended up with.”

Compare Schwimmer’s response to the comments that Lena Dunham would make more than a decade later, in response to similar criticisms of the first season of Girls — a show set in another borough of New York, but an equally white one.

“I really wrote the show from a gut-level place, and each character was a piece of me or based on someone close to me,” Dunham said. “And only later did I realize that it was four white girls. As much as I can say it was an accident, it was only later as the criticism came out, I thought, ‘I hear this and I want to respond to it. And this is a hard issue to speak to because all I want to do is sound sensitive and not say anything that will horrify anyone or make them feel more isolated, but I did write something that was super-specific to my experience, and I always want to avoid rendering an experience I can’t speak to accurately.”

Neither of these defenses is particularly compelling. But Dunham’s comments — the first of many she would make on this issue — seem a lot more considered than Schwimmer’s one-and-done argument that the all-white casting was a total coincidence, and that anyway, it didn’t bother him.

There’s no doubt that most television shows on big networks like NBC were almost entirely white in 1994. (So were most television writers’ rooms — including that of Friends. This resulted in far more serious off-screen issues, as evidenced in the infamous Friends lawsuit mounted by black female writers’ assistant Amaani Lyle in 2000, on the grounds of racial and sexual harassment.)

It would have been a significant change for Friends to start integrating more people of color into its guest roles and even extras. But Friends spent the better part of a decade as the number-one comedy on television — and eventually became the number-one show, period. If any series had the power to break that barrier, it was Friends. Instead, it took nine years for a black woman (with a full name! And an actual arc!) to appear on the show, when Aisha Tyler guest-starred as Charlie Wheeler.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19216548/141324933.jpg.jpg) NBC/NBCU Photo Bank via Getty Images

NBC/NBCU Photo Bank via Getty ImagesWhat if Friends had cast Tyler or another actress years earlier? What if it had set that precedent in the mid-’90s? Imagine how different things might have looked on all the many, many series that followed in its footsteps, trying to replicate the Friends formula. To quote another extremely white show about New York, I couldn’t help but wonder …

Is Rachel Jewish?

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19216429/138427199.jpg.jpg) NBC/NBCU Photo Bank via Getty Images

NBC/NBCU Photo Bank via Getty ImagesThis question isn’t often raised alongside the other diversity issues on Friends, but just Google “Is Rachel Green Jewish?” and you will uncover a whole corner of the internet debating it. Critics Emily Nussbaum and Molly Lambert discussed the matter at length on Twitter in 2014, with Nussbaum arguing that the name Rachel Green alone is, “unambiguous … it’s like naming her Shoshanna Lowenstein, in TV terms.”

Shortly thereafter, writer Lindsey Weber did her own investigation into the matter, referencing the many clues (many of which are straight-up stereotypes, like Rachel’s teenage nose job and orthodontist fiancé) that seem to clearly show — but very carefully not tell — that Rachel is Jewish.

It’s become such a hot topic over the years that even Friends creators Marta Kauffman and David Crane (both of whom are Jewish) have been asked to address it in various interviews. In 2011, Kauffman confirmed that Rachel is not only Jewish, but the only “real” Jew on the series, according to halachic law, because she has a Jewish mother. Ross and Monica, however, only have a Jewish father — though they are both identified early on as Jews. They even celebrate Hanukkah, that one time!

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19216418/908363.jpg.jpg) Warner Bros. Television

Warner Bros. TelevisionSo, why all the hush-hush around Rachel’s Jewish background? And why does Judaism seem to evaporate entirely as the series progresses? (By season seven, Monica is looking for a Christian minister to officiate her wedding.) The answer is gross, but obvious: Because Rachel was supposed to be the beloved girl next door — not just to Ross, but to everyone. And just as it was understood that audiences would accept an all-white Manhattan, it was also believed that they would not (and should not be asked to) accept a Jewish leading lady. That was the case for Rachel, and for Friends — both the most popular girls in school.

Indeed, it was the case for Seinfeld too, when it was on the air (from 1989 through 1998). That series is right up there with Fiddler on the Roof in terms of Jewish cultural treasures, yet Seinfeld was also critiqued for obfuscating the Judaism of its characters (as with Rachel, there is a similar internet debate over whether or not George Costanza is Jewish). As Jennifer Keishan Armstrong wrote in her book, Seinfeldia, the show was called out as alternatively, “Too Jewish. Not Jewish enough. Even ‘too self-hatingly Jewish.’”

Is Fat Monica fatphobic?

In interviews about my book, I’m often asked if Fat Monica would still appear as such if Friends were made today. Would audiences accept her? I think the answer is a sad “yes, the majority would.” Fat Monica is one of Friends’ trickiest issues — perhaps because, unlike other forms of prejudice, anti-fat bias is still widely socially accepted. Even unrepentant racists know their views won’t go over well with everybody. But it is still generally believed that being fat is bad and being thin is better — and that idea is reinforced in every form of media, not to mention a multi-billion-dollar diet industry reminding us constantly how terrible it is to not be a size four.

So it’s no wonder that audiences are on the fence about Fat Monica. I grew up as a fat kid, and never once expected to see a version of myself on screen — let alone a humanized one. At one point, I actually appreciated her because, after all, Fat Monica had a decent career, meaningful friendships, and even some semblance of a romantic life, all of which were things I’d never been taught to expect, given my hideous size-16 body.

It wasn’t until rewatching Friends in my 30s (when I was literally writing about body positivity and anti-diet culture for a living) that I realized, oh, Fat Monica sucks. Fat Monica isn’t even a person. She’s not Monica, fat. She’s a cartoon character, with a weird, scream-y voice and a totally different personality (if you can call an affinity for mayonnaise and Kit Kats a personality). Her entire life is eating and pining, and occasionally dancing to disco music with donuts in her hands for no reason. She’s a clown. And audiences still laugh at clowns.

Fat shaming, mockery and stereotyping may have gone out of style, but they still persist, on screen and off. Even lauded progressive comedies like Big Mouth treat fat characters less like people and more like tropes. Dramas too, like This Is Us, use fatness as a defining characteristic (and not a positive one). So, would Fat Monica still be accepted today? Probably. She might be met with backlash and her fair share of internet thinkpieces. She might do fewer donut dances. But she still wouldn’t be Monica, fat. She’d be Fat Monica.

What about Chandler’s dad?

Yeeeeeah, what about her. This character, and the treatment of her, is the clearest evidence that Friends was indeed a product of its era — an era that was awful for transgender people. I think viewers rightfully cringe when they see Chandler’s dad, and hear the way her family talks about her. Kauffman and Crane confirmed she was a trans woman, after Friends ended — though during its run, the term “transgender” wasn’t as widely known. On the show, she was mostly referred to as a gay man, a drag queen, or a cross-dresser. And she was always discussed with abject disdain.

This is probably a good place to point out that I’m a straight, cisgendered white lady, so when writing about these issues with Friends for my book, I made a point of speaking to people who were not. Considering how angry these topics made me, I expected a lot more outrage from people who were directly affected by them — especially when it came to Chandler’s dad. Instead, as trans writer/editor Mey Rude told me, she was “better than nothing.”

Rude explained that until she saw the Friends episodes with Chandler’s dad (who I refer to as such only for the sake of clarity; we never learn the name she actually goes by, aside from her stage name, Helena Handbasket) she’d seen virtually no other trans characters on TV — except for the occasional murder victim on Law & Order. So Rude used to sit in her college dorm room watching the trailer for the 2005 Felicity Huffman film Transamerica over and over again. As a young trans woman, not yet out, she was desperate for a hopeful story — anything that might indicate she wouldn’t end up totally ostracized or murdered. In Chandler’s dad, Rude saw a trans woman with a life: “She has a career, she has a boyfriend!” Yes, she is treated like absolute garbage at her son’s wedding. “But they do invite her to the wedding.”

Of course, there are other trans folks who justifiably argue that there’s nothing positive about featuring a trans woman who is used entirely as a punchline for hurtful, offensive, bad jokes. As Samantha Riedel wrote at Them, Friends’ “‘realistic’ portrayal of cultural attitudes toward queerness ended up reinforcing those same attitudes, not driving society forward.” (Riedel also observes that in the pilot, when Chandler “idly muses that he sometimes wishes to be a lesbian,” his friends respond by taking “every opportunity to deride his queer quirks.”)

Even Kathleen Turner, who played Chandler’s dad, acknowledges it wasn’t a good look for Friends: “I don’t think it’s aged well,” she said in 2018. “It was a 30-minute sitcom. It became a phenomenon, but no one ever took it seriously as a social comment.”

Turner’s point is an important one — and, I think, key to understanding why Friends’ legacy is so polarizing today. Was the show homophobic, racist, and willing to reduce marginalized people to punchlines? Yes. It wasn’t any more offensive than other series of its time, and it aired in an era when it was easier to survive scrutiny over issues of diversity and inclusion. But Friends blew up bigger than any of its peers, and its popularity has managed to endure into an era when we think very critically about the messages television shoves into our brains — especially television we’ve been consuming for 25 years.

No matter what side you fall on, the debate over Friends is a healthy one. It doesn’t take away from what’s magical about the series — the cast’s uncanny chemistry, the fine-tuned jokes that still make us laugh, PIVOT. Rather, it adds something just as valuable. Today, this comfort-food show serves an additional purpose: Friends highlights both how far we’ve come, and how much further we have to go.

Kelsey Miller is a freelance journalist and the author of I’ll Be There For You: The One About Friends. Follow her on Twitter and Instagram at @mskelseymiller.

Author: Kelsey Miller

Read More