The show’s long, lucrative run led to copycat after copycat after copycat — even long after it had left the air.

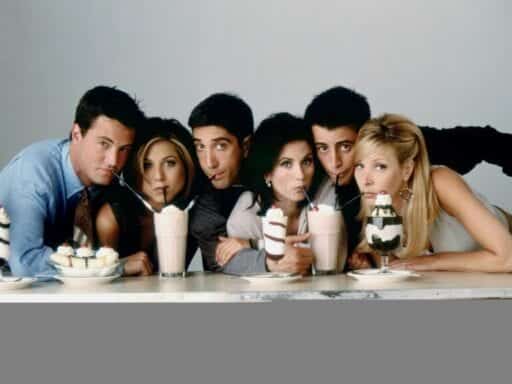

If you’re one of Friends’ many fans, you almost certainly remember the show as one of the best comedies of its era, a megahit that nonetheless possessed warm, funny, relatable characters and a surprisingly soapy storytelling style. It spawned hairstyles, catchphrases, and Ross and Rachel, perhaps the definitive will-they/won’t-they relationship of the ’90s.

Friends is one of those TV shows that has become strangely timeless, despite its very obvious ‘90s and early 2000s trappings. The show ran from 1994 to 2004, but it’s long been a staple in local and cable syndication, and when it arrived on Netflix in 2015, it found a whole new generation of fans, for whom the adventures of six attractive New Yorkers who could afford massive apartments while rarely seeming to work all that hard took on an even greater air of aspirational fantasy than the show had from the start.

But that’s not to say Friends is or has always been universally beloved. Even when it was airing, plenty of people criticized the show for its lack of diversity and its tendency to make jokes vaguely based in gay panic (particularly about Joey and Chandler, two roommates who fretted that people would think they were in a romantic relationship). And in the 2010s, talking about the elements of Friends less worth celebrating has become a bit of a cottage industry.

But as Friends arrives at its 25th birthday on September 22, 2019, let’s unpack a different side of the series’ legacy: the way in which it completely ruined TV comedy for a couple of decades.

Pretty people being funny

Okay, okay, if we’re being specific, then the network executives who have continued trying to copy Friends ruined TV comedy. Really, all Friends did was exist and become extremely popular. At its best, the show was a blast of fresh air, and even in its worst episodes, the talented ensemble cast was fun to hang around with.

But perhaps because Friends became one of the last, true TV megahits, lots of network execs decided that, hey, they should make their own version. How hard could it be? Since this was television, where copycats usually take the form of blurry Xeroxes, they copied only the most superficial elements of the show, which has happened to many a series throughout TV history.

But what’s weird about the copying of Friends is that it lasted well beyond the show’s run and even continues in some respects today, 15 years after the show went off the air. Networks can’t get it out of their heads that making a new Friends should be incredibly easy, and in the case of shows like New Girl and How I Met Your Mother, they actually kinda succeeded. (Really, though, HIMYM owes as much to the British Friends-alike Coupling and its inventive narrative trickery as it does the original. But that’s another article.)

Take, for instance, the makeup of the Friends cast. All six cast members were ridiculously attractive and funny, to boot. Conventional TV wisdom up to that point had been that pretty people often struggled with comedic timing, and if you look at the sitcom casts of previous eras, they rarely had more than a couple of conventionally attractive folks. Even in the case of, say, Ted Danson and Shelley Long of Cheers, both actors were good-looking, to be sure, but they were also just a little bit, shall we say, quirky, too.

I’m not trying to disparage anybody in the cast of Friends here. They all became stars in their own right, and both Jennifer Aniston and Lisa Kudrow won Emmys for their work on the show (and rightly so). It’s simply to say that it’s hard enough to find funny people. Once you add the restriction of also having those funny people be attractive people, it gets even harder.

Or, as longtime comedy writer Ken Levine (who wrote for both M.A.S.H. and Cheers among his many, many other credits) put it on his blog in a 2013 post about how Friends has made executives long for ensemble comedies about young, attractive singles: “I’ve always believed that for comedies you cast the funniest people. And often times those are not the most attractive. Today that would probably result in a big fight.”

Rise of the 20-somethings

Make a list of the biggest hit comedies of the past 20 years. Friends will be on there, of course, but so will Everybody Loves Raymond and Two and a Half Men. So will The Office and Modern Family. And so will long-running champ The Big Bang Theory. Yet outside of Modern Family (itself already a “family sitcom,” the most generic sitcom format of them all), how many of these shows have inspired legions of copycats to this day? Most of them haven’t. But Friends has. Shows attempting to be the new Friends march on and off the schedule every TV season with clockwork regularity.

Now I (and most TV fans) would probably welcome another Friends long before I’d welcome another Two and a Half Men. But it’s just weird that TV keeps tossing out parades of single 20- and 30-somethings in an attempt to copy a show that left the air 10 years ago. Granted, the success of HIMYM gave the format new life just when it might have started flagging, but even the shows that last past their first season — the New Girls and Happy Endings of the world — settle into a ratings-deprived state fairly quickly.

But most of these shows are just awful. You won’t remember most of them because they came and went so quickly, but TV keeps trying to make them happen. Throughout the 2010s, there have been shows like NBC’s A to Z (which sold itself as a forthright spin on HIMYM, actually, making it a copy of a copy of a copy if you’re following the lineage) and Marry Me (which at least had a few older characters in its ensemble though it was primarily quirky young folks), to say nothing of Fox’s Mulaney (which sold itself as a new spin on Seinfeld but still had tons of Friends in its DNA).

The number of Friends clones has tapered off somewhat in the last couple of years, though occasional Friends-adjacent shows like Netflix’s two-season Friends from College, CBS’s one-season Happy Together, and NBC’s one-season Champions still pop up here and there. But even as TV moves past its Friends obsession, a disproportionate focus on one particular type of comedy choked out lots of other promising types for too long.

And there’s something else the shows above have in common: They all flopped, many of them almost immediately, the fate of so many Friends clones.

Worse, the “singles bouncing in and out of love” genre has a tendency to immediately devolve into a conflictless “hangout sitcom,” the sort of show that rarely pushes its characters beyond the most surface-level tension. Comedy thrives on conflict and the hangout sitcom needs to deflate it, lest we wonder why the characters continue to hang out together.

But Friends will remain eternally alluring to network executives. As Jaime Weinman, a freelance writer and one of the world’s foremost experts in TV comedy, puts it, the format of the show promises something they love: youth.

“The theme of Friends is what people do when they’re not kids anymore but don’t quite feel or act like they’re adults yet. You can sell that idea because that’s a demographic that networks and advertisers are always trying to reach,” Weinman told me. “Writers want to pitch that idea because writers often feel stuck in that limbo between college and adulthood themselves, no matter how old they are.”

Is it any wonder Gen Z loves this show as much as their Gen X parents do?

Ross and Rachel and Monica and Chandler

For all of the ways that TV executives’ hunger to find the new Friends hurt broadcast TV comedy for many years, it also had at least one surprisingly beneficial effect: Friends solidified the idea of comedies having long-term story arcs with the success of its romances between Ross and Rachel and between Monica and Chandler.

Friends‘ greatest structural innovation was in taking the will-they/won’t-they structure Cheers had deployed so successfully and pushing it into the territory of the primetime soap. It gave viewers something to come back for week after week — and it gave the network big moments to promote. And that has been influential on nearly every comedy that airs on the screen today.

Go back to that list of big comedy hits. All of them have long-running story arcs that reach resolution very, very, very slowly. And while Cheers paved the way, Friends proved that viewers would sometimes come back just for the romance or for the characters’ career travails or even for fights between roommates.

That’s allowed for TV sitcoms to tackle more ambitious story structures, and it’s led to a landscape where everybody pretty much expects there to be continuing story elements in a sitcom, a marked contrast with the history of the medium. At first, executives forced these stories onto sitcom showrunners, but now they’re simply a part of the genre’s language.

“For better or worse, the basic idea of the sitcom since its inception — that most of the characters are basically in the same place all the time and so are their relationships — was threatened by Cheers but really demolished by Friends,” said Weinman. “Now we expect character relationships to be constantly evolving, to the point that we’re surprised if characters don’t get together and break up multiple times during a run.”

There’s one key reason for Friends‘ outsize influence I haven’t mentioned: the slow collapse of network television (and executives pining for the era when a show could be as big as Friends was). And the success of How I Met Your Mother and New Girl proved that with the right cast and right writers, this format can still be amazingly funny and successful.

But we too often think of TV shows as discrete units, things that run for a while then go off the air and reappear in reruns on TV Land or on Netflix. Really, however, TV is perhaps the medium most influenced by the other shows that are already airing — often because new series embrace what established ones do well. Friends might have left the air in 2004, but it also never really did. The seeds of its influence are sprouting all around us.

Author: Emily Todd VanDerWerff

Read More