Have you seen that high-speed rail map on Twitter? Gen Z is hoping President Biden has.

Cara only has about 700 followers on Twitter. The 20-year-old frequently garners a handful of “Likes” on her content, which consists mostly of takes on pop culture and singing videos.

But when she tweeted a popular image of a potential US high-speed rail map in January, saying “I want her so fucking much,” her tweet quickly went viral, earning over 185,000 “Likes” and more than 50,000 retweets.

I want her so fucking much pic.twitter.com/0xMMgW8pz1

— jon from garfield (@thisiscaramore) January 23, 2020

Such is the popularity among Gen Z-ers of high-speed rail.

“We look at other countries that have good examples of it, and we wonder why our country can’t do that,” Cara said. “It seems like a simple solution that we can’t find the reason as to why we’re not doing it.”

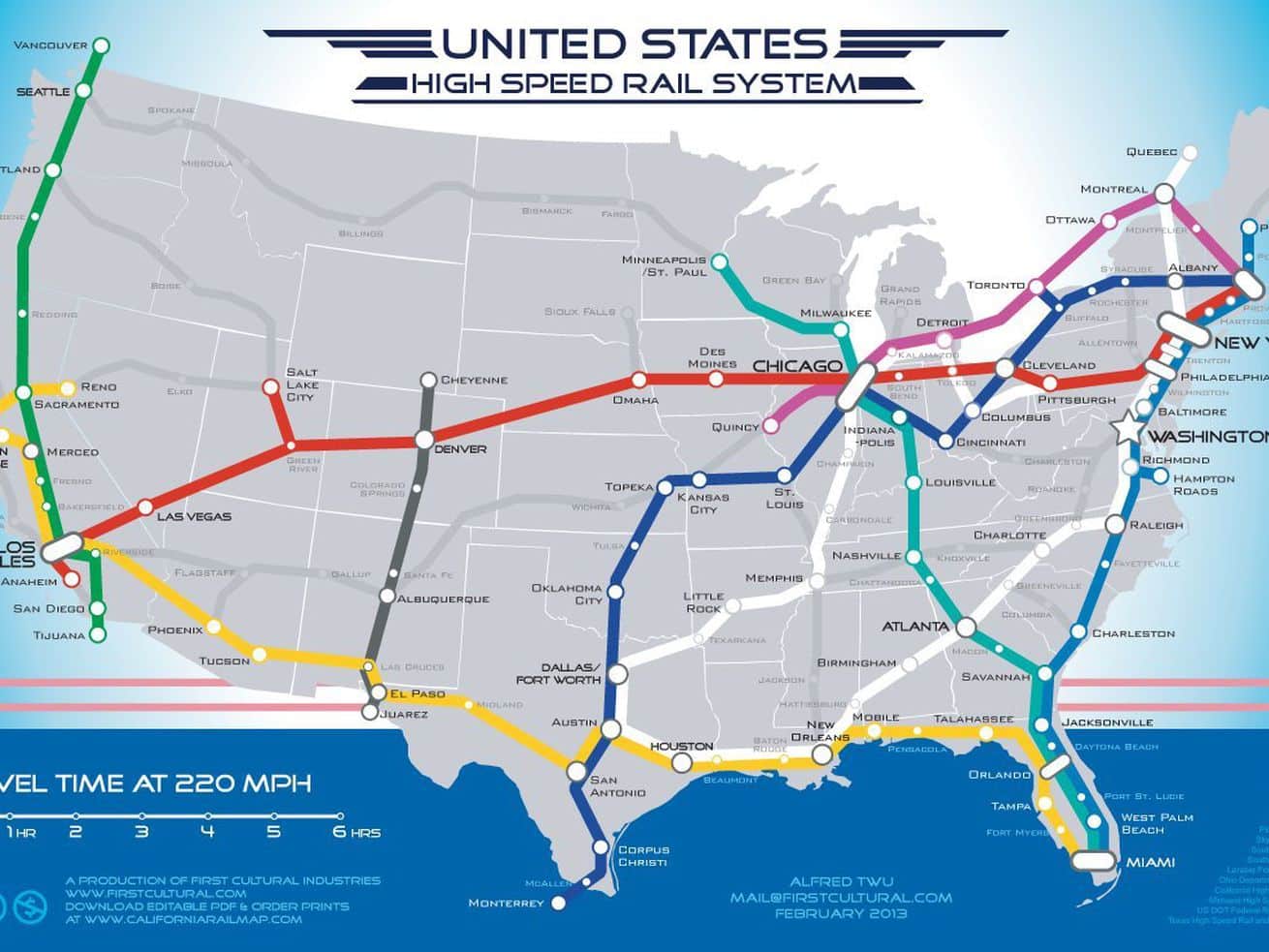

For members of the young online left, the high-speed rail map has become a ubiquitous fixture of politics Twitter. Created by graphic designer Alfred Twu in 2013, the map depicts a system of interconnected high-speed rail lines, linking Los Angeles to New York and Minneapolis to Miami, among other projects. (High-speed rail refers to lines that typically run over 160 miles per hour.)

The map has been tweeted out by tiny personal accounts and the Sunrise Movement alike. It has its share of problems — the proposed rail lines go right through tribal lands — but it serves as a handy analog for what the promise of high-speed rail represents to Generation Z.

“We are so much more connected with people across the country, across the world,” says Matt Nowling, a 21-year-old college student from Columbus, Ohio, who has worked on Democratic campaigns. “High-speed rail provides an opportunity for people to connect in a more sustainable manner. You don’t have to worry about your car, about gas. It’s just so much easier.”

you ever just think about the high speed rail system :,) pic.twitter.com/FrRtWBvXIn

— Sunrise Movement (@sunrisemvmt) July 19, 2020

High-speed rail infrastructure exists across Europe and Asia, where publicly owned and maintained tracks can connect passengers from Beijing to Hong Kong in nine hours, or Madrid to Barcelona in under three hours. In the United States, there is currently one high-speed rail line — arguably. Amtrak’s Acela Express, which runs through the Northeast Corridor from Boston to Washington, DC, can reach speeds of 165 miles per hour, but frequently runs at an average of 70 miles per hour between those cities.

Even with America’s resident Amtrak champion, Joe Biden, now in the White House, and the administration preparing a $2 trillion green infrastructure proposal, a network like the one in Twu’s map is at best decades away. To get there, the US would have to overcome a number of obstacles, from Republican and corporate opposition to a dearth of expertise. Perhaps most importantly, it would require a level of federal commitment — both budgetary and planning-wise — the likes of which have not been seen in generations.

The map, then, represents Gen Z’s ambitious, sincere wish — for a more connected, more sustainable future — and their inherent recognition of how impossible the dream of high-speed rail may be.

Gen Z loves high-speed rail, but no one’s really fighting for it

Gen Z isn’t the first group of young, online voters to care about transit. But they represent a culmination of trends that have been building in younger Americans: less interest in cars as status symbols, more interest in environmentally friendly transit methods.

The popularity of the high-speed rail map meme builds on years of similar conversation, some of it in the Facebook group New Urbanist Memes for Transit-Oriented Teens (Numtot), first created in 2017 and now serving as a “haven for people who love trains,” as administrator Emily Orenstein described it. The meme, and high-speed rail more generally, are popular topics with the group’s more than 200,000 users, its three administrators say, because it allows them to dream big.

“I love the high-speed rail map image because I think a lot of urban planning and urbanism today, especially in the United States, is so devoid of inspiration because it’s so beaten down by so-called pragmatism, labor costs, legal issues, things like that,” said Jonathan Marty, a Numtot administrator who goes to Columbia University. “The high-speed rail thing, the map that circulates a lot, it touches people because it’s this genuinely bold and tangible image of the future. People can feel that.”

In addition, high-speed rail is a blunt example of just how behind the US is. After the 2008 global financial crisis, China, in particular, made massive investments into high-speed rail, building over 15,000 miles of rail lines that service more than 1.7 billion passengers yearly, according to the World Bank. And the high-speed TGV in France, for example, goes 200 miles per hour.

“At that speed, you could get from New York City to Chicago in about four hours,” Juliet Eldred, a Numtot co-founder and transit planner, said. “The current train is about 20 hours. That makes me viscerally enraged.”

High-speed rail also checks a lot of boxes for the young left that’s interested in traveling but conscious of its carbon-intensive consequences. As Vox’s Umair Irfan explained, “high-speed trains run on electricity, which is only as clean as the generators that produce it,” but it’s definitely less carbon-intensive than flying:

A 2018 study in the Journal of Advanced Transportation looking at transit in Europe reported “a remarkable advantage of high speed trains compared to aircraft, with regard to direct [CO2-equivalent] emissions per [passenger-kilometer].”

It will likely never fully replace air travel or cars, but particularly for short-haul flights, Irfan notes, high-speed rail could give “travelers more options if they don’t want to fly.” And it can help achieve equity for low-income and minority communities, which have disproportionately low access to adequate transit infrastructure, the Department of Transportation has found.

Equity is a common benefit transit advocates cite for a number of different projects: With poverty increasing most quickly in the suburbs, the Numtot admins said better local light rail systems, for instance, could help strike a balance between the expenses of either living in increasingly unaffordable cities or taking on the costs of car ownership in a suburb.

“People don’t necessarily think about [transportation policy] in the same way they think of health care or housing, but fundamentally, having options that are safe and affordable and sustainable and effective and efficient is where we need to be,” Eldred said.

But while better-funded light rail and redesigning a city bus network fall into the push for transportation justice, they are not quite as sexy as a national high-speed rail project. And that’s the catch: High-speed rail is bold and attention-grabbing, but the scale of the project makes it near impossible.

Despite Gen Z’s enthusiasm, there aren’t high-profile advocacy groups for high-speed rail specifically, nor are there large protests against competing methods of travel — unlike, say, the March for Our Lives gun violence actions, or the organized protests against oil pipelines.

Fighting for high-speed rail is something Sunrise, for example, is passionate about and considers part of the Green New Deal, according to press secretary Ellen Sciales. But it does not get a specific mention in the group’s priorities for action in the first year of the Biden administration, though investing in “clean and equitable infrastructure projects” does.

“I don’t think people can conceive of a world that isn’t designed around cars,” Marty said. “But you can see in infrastructure projects, you can do this. A big part of that fight is helping people to imagine a world in which that is possible.”

Why America still does not have a high-speed rail network

In the 19th and early 20th centuries, rail was a fundamental part of the US’s transportation ecosystem. But after World War II, the US instead chose to subsidize the interstate highway system and the aviation industry through massive investment and deregulation, respectively, leaving the railroad industry unable to compete without federal investment.

In the early 1970s, the federal government finally got into the railroad game by buying rail networks that had gone bankrupt to create Amtrak, a quasi-public corporation owned by the government. But any momentum fizzled with a 1980s move toward smaller government.

“We have a federal government system that perhaps had a moment of national purpose in the years following World War II that allowed the creation of the Interstate Highway System, but then fell apart,” Yonah Freemark, a senior researcher at the Urban Institute, said.

How you gonna do a US remake of a movie whose plot revolves around high-speed rail infrastructurehttps://t.co/71KAOlz9zK

— Zack Budryk (@BudrykZack) February 19, 2021

A number of significant challenges have prevented high-speed rail projects from getting started: the multistate nature of the projects, Republican and corporate opposition, and a lack of resources.

There have been moments in Democratic presidencies when it looked like rail was poised for a comeback. In the 1990s, President Bill Clinton secured funding for the improvement of Amtrak trains in the Northeast Corridor, leading to the opening of the Acela Express in 2000.

President Barack Obama came into office in 2009 with plans to include massive infrastructure improvements as part of the American Recovery Act. But he got just $8 billion for new rail projects passed — and Republican governors promptly shot down the funding offers in Florida, Ohio, and Wisconsin.

One project in California successfully received federal funding in 2010. The line will run from Anaheim to Los Angeles to San Francisco, and is expected to open in 2029 — though its continual delays have become a popular punching bag for California Republicans.

“National planning has not been fully accepted, especially by the Republican Party,” Freemark said. “It’s a multilevel, multistate decision-making process that requires decades of commitment. It’s just not something we have had in the US.”

Joe Szabo headed the Federal Railroad Administration from 2009 to early 2015. He remembered the early days of the Obama administration as “incredibly exciting.” But the newness of the grant program, Republican opposition, and a lack of “predictable, dedicated funding” for rail projects squelched a lot of the early optimism.

“For high-speed rail to succeed, it can’t be done with fits and starts,” Szabo said. “Major projects take years to build out, and so there has to be predictability.”

When President Dwight Eisenhower authorized the Interstate Highway System, Congress created a Highway Trust Fund to pay for the construction, and guaranteed states that the federal government would pay for 90 percent of the construction costs. Based on a planned national map, the federal government issued contracts to states to commission roadways.

The project took 35 years, and is still a partnership between federal and state agencies — highways are owned and maintained by the states they are in, but have reliable federal funding. Rail, however, does not enjoy the same federal financial commitment.

Additionally, Freemark said, there is a shortage of institutional rail knowledge among engineers at state transportation departments, where most employees focus on highways. Szabo confirmed this. He said one state he worked with had half an employee focused on rail among the hundreds of employees at the department.

“Here’s the key — it takes a strong federal partner,” Szabo said. “That is the piece that has been missing for rail. There are states that have interest in building out good projects, but there hasn’t been a strong federal partner for rail like there has been for highways and roads.”

In addition, there are strong, moneyed interests lined up against the construction of a high-speed rail network, including the Koch brothers, who have poured millions into killing projects through advertising, think tanks, and donating to GOP politicians.

Andy Kunz is the president and CEO of the US High Speed Rail Association (USHSR), a trade group that advocates for high-speed rail. The group launched in 2009, and despite the energy around high-speed rail in the Obama administration, Kunz says it was swiftly met with an apparatus of opposition.

“We were up against this nonstop anti-rail propaganda machine cranking out lies and myths — rail is yesterday’s technology, all this nonsense — from these think tanks funded by oil companies and car companies and the road industry and the aviation industry,” he said.

All of these challenges have proven frustrating to everyone from officials in the Obama administration to the Gen Z-ers who champion the map meme. The type of system depicted by the map, by definition, would require political consensus and investment because it would be a decades-long initiative.

“Are we willing, as a nation, to make the sort of generational commitment to mode shift in transportation that is necessary to make HSR effective?” Freemark said. “I haven’t seen that.”

“A generational opportunity”

If there were ever a president to champion high-speed rail, it would be Joe Biden.

“Amtrak Joe” used to travel by train daily as a senator. Szabo said in his time at the FRA, it was the then-vice president who always asked for briefings on passenger rail. And during the Democratic primary campaigns, he made a frequent commitment to prioritizing rail.

“My administration will spark the second great railroad revolution to propel our nation’s infrastructure into the future and help solve the climate emergency,” Biden said in December 2019.

Infrastructure is expected to be Democrats’ next project after Covid-19 relief. It’s the rare idea that attracts both wings of the Democratic Party — left-wing Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-VT) is already working with the White House on shepherding an infrastructure bill through the budget reconciliation process, while centrist Sen. Joe Manchin (D-WV) has called for up to $4 trillion in spending on infrastructure.

The Biden plan calls for providing every city with high-quality, zero-emissions public transportation options, including funding rail projects and creating the cleanest, fastest rail system in the world. It’s an ambition new Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg has shared — he wants the US to become a global leader in high-speed rail.

USHSR released a five-point plan for feasible things Biden can include in the infrastructure bill or do on his own, including fast-tracking existing, ready-to-go projects that need funding, creating a high-speed rail development authority within the federal Department of Transportation, and selecting suggested second-tier projects, mostly across the Midwest and South, for immediate funding and planning assistance. Kunz believes that, realistically, the Biden administration could lay the groundwork for a rail system that replaces short-haul flights.

“It seems like now, a lot of the planets are lining up that we can actually do this and push the tipping point,” Kunz said. “It’s a real fork in the road.”

In thinking about the immediate future, Kunz is an optimist. (More on the pessimists — or realists, as they would say — later).

Szabo is with Kunz. He said Biden is assembling a strong transportation team with lots of rail expertise. Unlike in his time, the DOT now has greater internal infrastructure and readiness to pursue rail projects.

And existing projects are already jockeying for funding in anticipation of the infrastructure package, according to Bloomberg’s CityLab.

Other projects throughout the country, some of which already have funding from the private sector, are preparing for an influx of federal funding, developing equity and environmental standards to prove project viability.

Szabo and Kunz also believe 2021 will not be a repeat of 2009, when Obama’s best-laid plans were derailed, because climate change has forced the issue. Global warming is a much more accepted and visible problem than it was in 2009, and a much greater priority for Biden than it was for Obama in his first term.

Other experts — and some of the Gen Z voters I spoke with, drawing on a lifetime of governmental disappointment — are not nearly as hopeful.

“These projects take decades to get implemented and are just at the opening stages of what would be required to do that,” Freemark said. “It’s worth pointing out that the Obama administration said the exact same thing in 2009. We don’t have the evidence yet that this is going to be any real commitment in the long term.”

Already, Biden and Buttigieg’s comments praising rail have received pushback from Republican-aligned groups, like the libertarian Cato Institute, which has suggested high-speed rail is useless, outmoded technology.

Secretary of Transportation Pete Buttigieg wants to make the United States the “global leader” in high‐speed rail. That’s like wanting to be the world leader in electric typewriters, rotary telephones, or steam locomotives. https://t.co/gUXX4Ctd8Q #CatoTransit pic.twitter.com/ukXgxZEX2S

— Cato Institute (@CatoInstitute) February 14, 2021

Additionally, high-speed rail is just one of many environmental and equity issues Gen Z is agitating for — and Biden’s window to enact new policy, especially if Democrats lose the 2022 midterms, is limited.

The Numtot administrators were cautiously optimistic about rail’s potential but had concerns about the similarities between the present moment and Obama’s first term.

“We had a Democratic administration that wanted sweeping change, and it didn’t happen,” Orenstein said. “The people’s idea of what kind of change is possible maybe doesn’t match Washington’s idea of what kind of sweeping change we can and should be doing.”

Even with a perfect storm of opportunity, Cara, who posted the high-speed rail meme, is not confident she’ll ever see a system like the one in the map.

At 20, she has not been particularly encouraged by the government action — or lack thereof — she’s seen throughout her life, from climate inaction to political gridlock to multiple recessions.

“I would like to see a proposal come about within this administration,” she said. “Do I think it’s going to happen? Probably not.”

Author: Gabby Birenbaum

Read More