The Harry Potter book series helped me realize I’m nonbinary. Now I know that had nothing to do with J.K. Rowling.

Last weekend, as Harry Potter fans the world over were still reeling from the latest round of anti-trans comments made by author J.K. Rowling, I boxed up 21 years of my life.

Over the past few years, Rowling has made several statements that suggest a growing alliance with TERFism — trans-exclusionary radical feminism, or the belief that trans women aren’t women and that biological sex is the only factor that determines someone’s gender. Many Harry Potter fans had previously voiced concerns that Rowling might be anti-trans, but despite their efforts, the author’s apparent TERFism wasn’t widely discussed until December 2019, when she suddenly tweeted in support of a British TERF at the center of a highly publicized court case.

Though Rowling was met with massive backlash at the time, she’s continued to double down on her views. On June 6, she appeared to openly belittle transgender people when she mocked a news headline about “people who menstruate.”

“I’m sure there used to be a word for those people. Someone help me out. Wumben? Wimpund? Woomud?” Rowling tweeted, seeming to imply that all people who menstruate are women and that only people who menstruate are women.

Rowling’s comment deeply hurt many of her millions of fans — including me. More importantly, it perpetuated the type of pernicious hate and misinformation that leads to trans women, especially teens and black trans women, becoming victims of sexual assault, violence, and hate crimes at an appallingly frequent rate.

And so, on Sunday night, I removed Rowling from my bookshelf and stored her away: all 11 books in the Harry Potter series (seven novels, plus three supplementary books and one play script); The Casual Vacancy, her scathing satirical foray into “adult” literature; and her four Robert Galbraith mysteries. In boxing up those books, I metaphorically boxed up years of intense participation in the Harry Potter fandom, from writing fanfiction and going to conventions to moderating fan communities online and nurturing the friendships I made within them. I still talk nearly every day to people I’ve known in Harry Potter fandom since my earliest days there. I resolved to compartmentalize my Harry Potter fandom identity as something over and done with, instead of thinking of it as a cornerstone of my identity.

Then on Wednesday, Rowling attempted to explain her stance on trans identity with a long essay full of harmful transphobic stereotypes. It was a profoundly hurtful piece of writing, riddled with hand-wringing, groundless arguments about villainous trans women, outdated science, and exclusionary viewpoints. Especially gutting was the essay’s self-centeredness; Rowling masked obvious transphobia as a personal appeal to reason, rooted in her own experience as a woman and an abuse survivor. She asked for empathy and respect for her own experiences while showing none for her targets.

But even before she published it, to me at least, the damage had already been done. I had officially ended a 20-year relationship and started to grieve.

Like many fans, I’ve spent years critiquing the many problems embedded in J.K. Rowling’s stories: their arguable racism, queerbaiting, lack of multiculturalism, fat-shaming, and upholding of the patriarchal structures she established in her intricately detailed Wizarding World. (And if you think that the Harry Potter books are just children’s stories, not worthy of this kind of real-world framework or critique, consider that Harry Potter bred several generations of Democrats.)

Perhaps I should have reached my limit earlier; I’m queer, I’m fat, I strive to be an ally to people of color. But fiction is malleable — you can tell yourself that with any given work there are extenuating circumstances, contradictions, multiple interpretations. Besides, many fans have spent years if not decades calling out the Harry Potter books for their shortcomings, and often actively transforming the world of Harry Potter into something better through fandom and its many offshoots, all while still loving it.

For my own part, I would have forgiven and overlooked most of Rowling’s fictional flaws and foibles — including the ugly moment of transphobia in her Robert Galbraith novel The Silkworm. But it’s impossible to ignore direct and repeated examples of bigotry when they come from Rowling herself, a woman who’s doubled down on her transphobic statements after months of heartbroken fans of her work expressing how hurtful those statements are.

It doesn’t help that Rowling truly is targeting one of society’s most vulnerable communities: In 2017, research found that a staggering 44 percent of trans teens in the US had seriously contemplated suicide, while more than half had experienced long periods of feeling sad or hopeless. And that was before many of them found out that a beloved author thinks their identity is a joke. It’s the kind of statement that feels even more hurtful, even more raw and vicious, because Rowling clearly has access to information about the struggles trans and nonbinary people face when it comes to depression, homelessness, sexual assault, and hate crimes, yet she chooses to use her massive platform to further attack us anyway.

And maybe that’s the ultimate reason why Rowling’s latest comments were the final straw for me — it’s just too personal. Because my time in Harry Potter fandom may be one of the most significant parts of my life, but an even more significant part of my life is that I’m nonbinary.

It took me a very long time to figure out I was genderqueer, and when it finally clicked, one of my biggest revelations was that I’d spent years mapping my own identity onto fictional characters without realizing it — above all, Tonks in Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix. I vividly remember the visceral excitement I felt the first time I read the fifth Harry Potter book in 2003 and met Nymphadora Tonks, a shapeshifter with spiky pink hair, a punk-rock aesthetic, and an insistence on being called by her gender-neutral last name. I was certain that Rowling had written a canonically genderfluid character. Like millions of other Harry Potter fans who dared to project ourselves into the books, I was ultimately disappointed: By the end of the series, Tonks was a married, fully binary woman, softer and gentler, letting her husband feminize her as “Dora” — a name she’d previously hated.

I have always wondered if Rowling set up Tonks to somehow be “tamed” in the later books, from her earlier nonbinary presentation in Order of the Phoenix, and I’ve always written it off as surely not conscious. As a sickening byproduct of Rowling’s transphobic screed on Wednesday, I now realize I was actually right to have been wary all along. Rowling argues in the essay for the scientifically flawed and emotionally abusive narrative that “gender dysphoric teens will grow out of their dysphoria,” and uses herself as an example of a teen who felt “mentally sexless” before eventually — “fortunately” — growing out of feeling “confused, dark, both sexual and non-sexual.”

I read this passage as a chilling, heartbreaking confirmation that Rowling wrote Tonks not as an affirmation, even a subconscious one, of trans identity, but as a conscious repudiation of it: She deliberately created Tonks as a dsyphoric individual so that the character could “grow out of” her dysphoria, subtly perpetuating the transphobic narrative that gender dysphoria is a choice. She consciously took the shapeshifting nonbinary character, who helped me figure out (well into adulthood) that I was genderqueer, and made her “grow” into being cisgender.

It’s hard to articulate how upsetting that realization is. A few months before Order of the Phoenix was published in 2003, I participated in a letter-writing project for Rowling. I parked myself in a café one day and spent hours trying to convey everything I felt for Harry Potter — all of my joy, fear, wariness, and hope for what the rest of the series would be, all in what turned out to be a nine-page, handwritten letter. That day has always been a precious memory to me, and it feels unbelievably hollow to look back now and realize that while I’d entrusted so much of myself to the author, she had been plotting on some tiny level to erase me.

None of this changes what Tonks means to me. She remains the character who innately reflected my own nonbinary nature before I even fully understood it myself. She’s the Tonks I created, not the one Rowling gave me — not the character who ended the books, but the Tonks who began them.

With Rowling herself, though, such a tidy conclusion is harder to draw. Harry Potter fans can say we want to keep the Rowling we started the books with, not the one we have now, but that’s difficult: The Rowling we have now is still tweeting. And no effort to separate the art from the artist can ever be fully successful when the artist is right there, reminding you that she intended for her art to reflect her prejudice all along.

I’ve thought, written about, and talked about cancel culture a lot over the past few years. People often ask me if I think it really exists — if “canceling” someone can have any meaningful effect, or whether it’s entirely a performative stance. But I think that question flattens cancel culture’s power. To me, “canceling” someone can’t be about punishing one individual or ruining their career; even if humanity could agree on what social crimes were worth punishing, no one wants to live in a world where you can be blacklisted from existence, like in that one episode of Black Mirror.

Instead, I think cancel culture is best treated like a collective decision to minimize the cultural influence a person and their work have moving forward. This approach has already been applied to some 20th-century figures whose art is now almost always foregrounded within the context of what remains problematic about it: White supremacists Ezra Pound and H.P. Lovecraft, and the white supremacist film Birth of a Nation, are the clearest, most well-known examples, but society has also recalibrated the way we discuss more recent creators like Woody Allen and Michael Jackson. In all of these controversial cases, the approach usually winds up being one of compromise: No one wants to lose Cthulhu or “Thriller” or Annie Hall, but we also can no longer talk about any of those stories without making it clear that they were created by bigots or predators.

With J.K. Rowling, we’ve reached that point nearly in real time. Already, we can no longer talk about Harry Potter without foregrounding the prejudice lurking beneath the surface-level morality of Rowling’s stories. Many aspects of Harry Potter are already up for debate and reevaluation. The sad and messy truth is that Rowling’s transphobic comments may have ruined Harry Potter for many of its fans.

But Harry Potter is simply too big a cultural landmark to jettison. I don’t believe anyone wants to mind-wipe Harry Potter’s existence from the world; it means too much to too many of us. (Let’s leave aside the nonsensical whatever of Rowling’s Fantastic Beasts films.) But I also find myself bristling at the jokes that have invaded social media in the wake of Rowling’s comments — the ones fantasizing that the Harry Potter books magically appeared unto us with no author, or that they were written by someone else we like better. Sure, the author is dead, but that idea is about reclaiming agency over our own interpretation of a text. It paradoxically depends on the author having a proprietary interpretation of their own work — one that we can then reject.

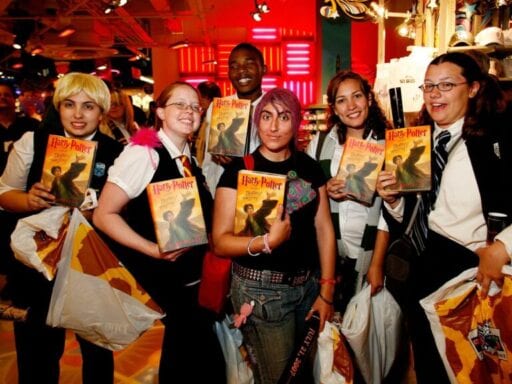

That’s important, because despite its flaws, Harry Potter has influenced generations of kids to grow into progressives who then turned out to be more progressive than the books themselves and the woman who authored them. The series embodies what people in fandom mean when we say that fandom is transformative: The fans who sorted themselves into Hogwarts houses, sewed cosplay, wrote fanfic, played Quidditch, stanned Wizard Rock, swarmed stores for midnight book launches — they did all of that, not J.K. Rowling. Their passion made Harry Potter into the cultural phenomenon it is today.

By repudiating Rowling’s anti-trans comments, millions of Harry Potter fans are also turning the series into a symbol of the power of a collective voice to drown out an individual one. The power of fans’ love and empathy for trans people and other vulnerable communities, and their steady rejection of Rowling’s prejudice, is a potent, raw form of cancellation — one undertaken not out of a spirit of scorn and ostracism, but with something closer to real grief — and it deserves to be a part of the story of Harry Potter.

But if we can’t erase Rowling, what can we do instead? We can break up with her.

We can grieve, nurse our wounds, and be sad we loved someone who hurt us so badly. We can celebrate happier times while mourning a relationship we outgrew, that became toxic, and regretting the time we spent waiting for a problematic fave to change and grow. We can give ourselves time to heal. And we can consider accepting that the microaggressions we may have noticed in Rowling’s books themselves were, perhaps, warning signs obscured by a benevolent, liberal exterior.

Jo can keep the money, and Pottermore and Cormoran Strike, and definitely all of Fantastic Beasts. She can keep the house elves who really love their enslavement, the anti-Semitic goblin stereotypes, Dolores Umbridge, Voldemort, Dementors, and Rita Skeeter. I’ll take Harry and Hermione and Ron and Draco, Luna and Neville and Dumbledore’s Army. I’ll take Hogwarts and pumpkin pasties and butterbeer and Weasley’s Wizard Wheezes, and every other moment of magic and love this series has given me and countless others.

Trans and queer Harry Potter fans get to keep Tonks and Remus and Sirius Black and Charlie Weasley and Draco, because I say so; Harry Potter is ours now and we make the rules. J.K. Rowling lost custody over her kids and now we can spoil them, let them get tattoos, express themselves however they want, love whoever they want, transition if they want, practice as much radical empathy and anarchy as they want. Harry Potter is Desi now. Hermione Granger is black. The Weasleys are Jewish. Dumbledore’s Army is Antifa. They’re anything you want and need them to be, because they were always for you.

As for me, I won’t be reading or rereading Harry Potter any time soon. I have endless Harry Potter fanfiction and novels written by Harry Potter fans who grew up to explore instead. Above all, I have the Wizarding World that lives on in my heart, queer, genderqueer, deviant, diverse, and currently defunding the Aurors.

That’s the Harry Potter we all created, together, without J.K. Rowling. And we all know that’s the version that matters, in the end.

Support Vox’s explanatory journalism

Every day at Vox, we aim to answer your most important questions and provide you, and our audience around the world, with information that has the power to save lives. Our mission has never been more vital than it is in this moment: to empower you through understanding. Vox’s work is reaching more people than ever, but our distinctive brand of explanatory journalism takes resources — particularly during a pandemic and an economic downturn. Your financial contribution will not constitute a donation, but it will enable our staff to continue to offer free articles, videos, and podcasts at the quality and volume that this moment requires. Please consider making a contribution to Vox today.

Author: Aja Romano

Read More