On “cheugy” and the internet’s endless fascination with out-of-touch white women.

Hey bestie! Do you keep logging onto the internet and seeing people calling each other “bestie” and “girlie” and “girlboss” and “queen,” and you sort of get the sense that these words are on some level being used ironically but also you aren’t totally sure what the joke is?

If you spend a lot of time reading TikTok comments, the most brutal and hilarious place on the internet, you almost certainly have. There, everyone is “bestie.” Regardless of whether you are wonderful or absolutely suck, you are “queen.” Did you have a really bad opinion on something you don’t know anything about? “Hey girlboss it’s not too late to take this down <3” Did you post something that you thought was a flex but it ended up being a self-own? Someone will have commented “hey bestie I can’t do this today!”

“Besties” and “girlbosses” have neither gender nor profession; even if you are an old man, on TikTok you are “girlie.”

It’s a joke, even when it’s not — you can comment “ok bestie you BODIED this” on a TikTok of someone wearing a cute outfit — the joke being the fact that you’re saying the word “bestie” to a stranger on the internet. In other words, the fun of “hey girlie” is that you get to role-play as someone who would actually call a stranger on the internet “girlie.” In other-other words, you’re also sort of ironically appropriating MLM culture.

MLMs, or multi-level marketing companies, have been a subject of fascination on the internet for more than a decade. Companies that operate with an MLM structure (also sometimes called “network marketing” or “direct sales”) rely on individual sellers to recruit others to join the business, creating a pyramid-like system in which the biggest successes aren’t the people who sell the most product, they’re the ones who recruit the most sellers. MLMs like LulaRoe, LipSense, and Young Living encourage members to exploit the relationships they already have and create a false sense of intimacy with people they barely know — i.e., calling a distant acquaintance a “bestie” before sending them a sales pitch.

A portrait of the typical MLM participant has dominated: a white, suburban woman in her 20s or 30s who’s either married or perpetually engaged, who probably loves Disney and Christian self-help evangelist Rachel Hollis, and who posts grainy images that say “But first, coffee” to her Instagram. There are plenty of women like this, but the internet’s obsession with them goes deeper than just the numbers. For at least the last decade, we’ve endured several new dictionary definitions for what it means to be an embarrassing kind of white woman: First we had the Pumpkin Spice Latte-drinking “basic bitch,” then there was “Christian Girl Autumn,” a play on “Hot Girl Summer,” the same year that “VSCO girl” became the de facto way to describe middle-class teenage girls who wore oversized T-shirt and puka shell necklaces. And as of last Friday, we have a new term to describe the same kind of cringey, out-of-touch basic person: “cheugy.”

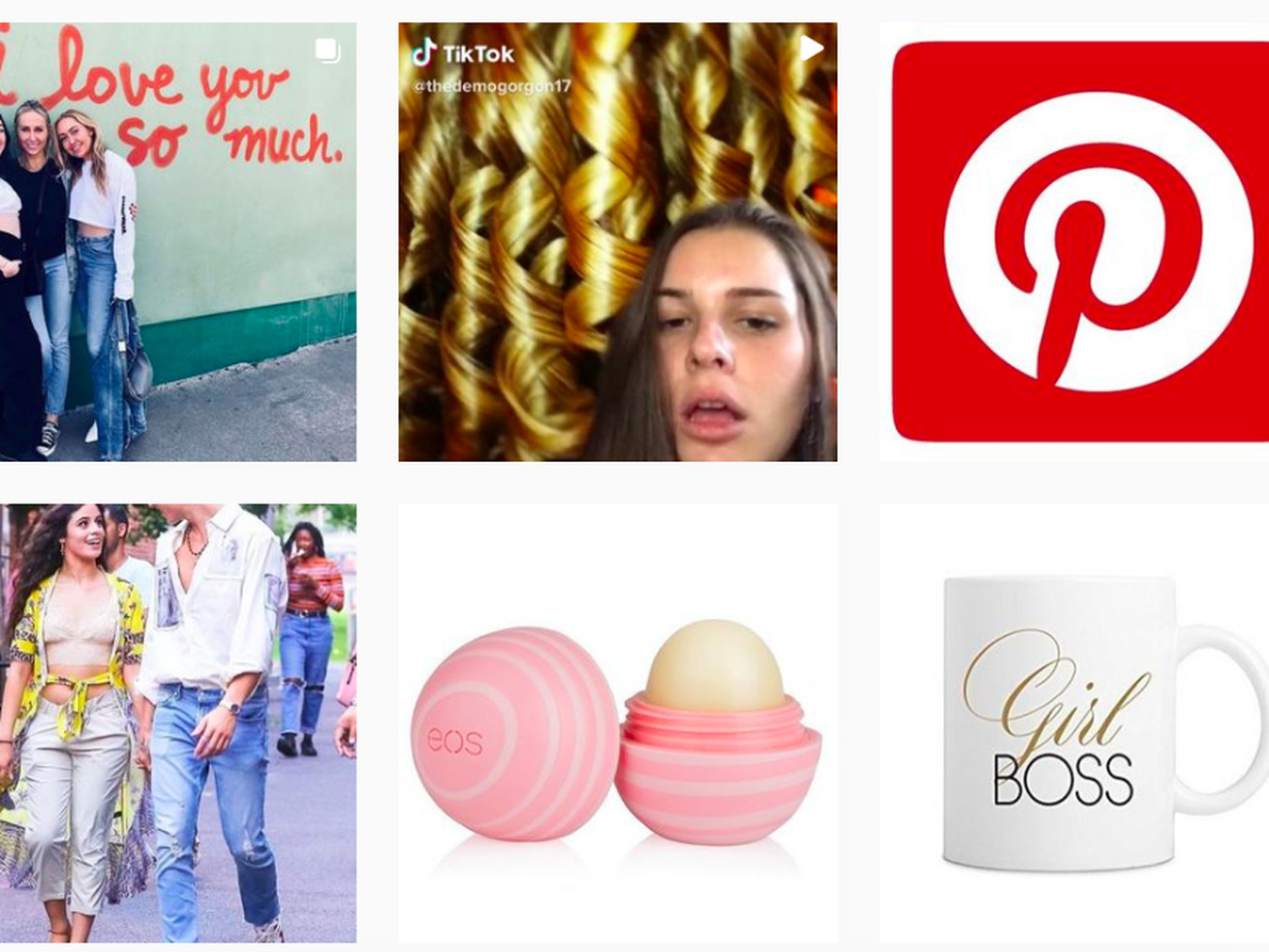

What is “cheugy,” a word I came across precisely once in a relatively niche TikTok a couple weeks ago and never heard again until the New York Times’s digital trend oracle Taylor Lorenz wrote about it last week and is now all over the internet? “Cheugy,” according to its inventor, 23-year-old software developer Gaby Rasson, can be used to describe “people who [are] slightly off-trend,” outdated, or even just generally “off” in the same way that a high school classmate DMing you to buy her essential oils feels. The aesthetic is chevron print, Instagram posts captioned with “I did a thing,” and the twirly, curly font adorning every Etsy product tagged “bridesmaid.” The Instagram account @cheuglife, which documents particularly cheugy offenses, includes pictures of Ugg slippers, #girlboss mugs, Minions memes, Smirnoff raspberry vodka, and, hilariously, cake pops.

The original TikTok, which got about 100,000 likes (Twitter viral, but not TikTok viral), makes clear that very few people are actually saying “cheugy.” It was presented more as a pitch, a term that might be useful in your life in case you and your friends needed it. In her explainer, Lorenz emphasizes the point, making clear that this was simply a term that spread among a few groups of friends at summer camp and sororities, not a wildly common phrase.

Then, something predictable happened: The story went viral, and as of this weekend, “cheugy” is everywhere. Though she couldn’t tell me how many pageviews it has, Lorenz said it was one of the most-read recent stories in the Styles section — right below an explainer on Rachel Hollis. The meaning is clear: People are extremely fascinated by this specific kind of person, whether it’s because they’re reminded of cheugy #girlbosses in their own life or out of a desire to separate themselves. “People love to bash this specific type of person, a privileged white person, and especially sorority types,” Lorenz told me. “Any time you can name that backlash or articulate it, it pops off.”

While it’s easy to claim it all as outright misogyny, Rolling Stone’s EJ Dickson makes a good point: “Misogyny is insidious and takes many forms in our culture, but making fun of someone for posting Minion memes is not one of them.” Much more than sexism, I’m reminded of spaces on the internet where people cosplay as other types of internet users, like Facebook’s iconic “a group where we all pretend to be boomers” or Caroline Moss and Michelle Markowitz’s delightful book Hey Ladies, a fictional parody of a bridal party email chain.

“Cheugy,” to me, feels less like an attack on someone else and more like self-deprecation, a way to poke fun at our past selves who actually did earnestly love chevron and aspired to be a girlboss. A little part of us probably wishes that we were less online and had fewer irony-poisoned brain cells, living in a world where we were completely unaware of the term “cheugy” and instead just lived it. Am I right, bestie?

This column first published in The Goods newsletter. Sign up here so you don’t miss the next one, plus get newsletter exclusives.

Author: Rebecca Jennings

Read More