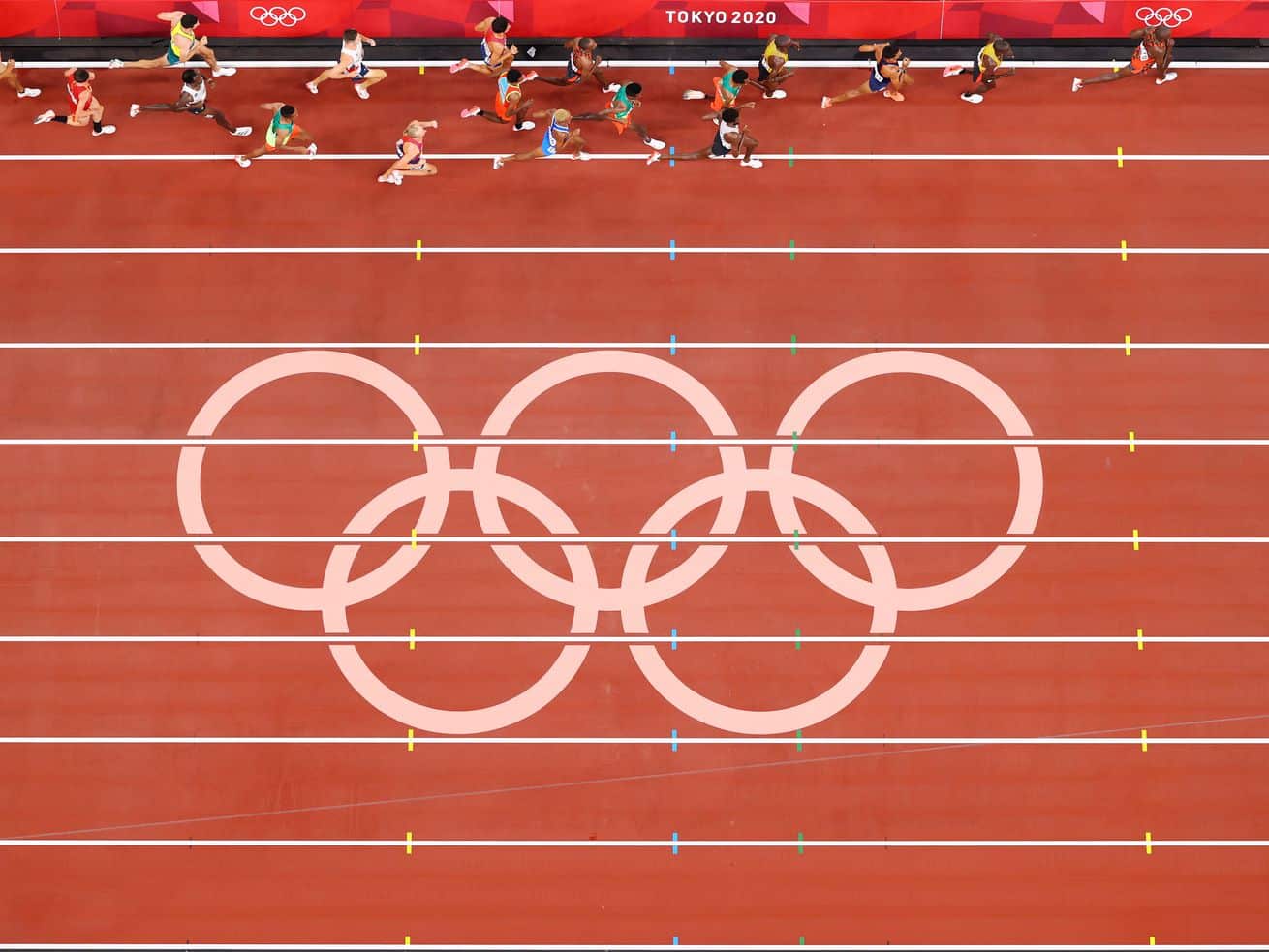

The Tokyo Olympics could cost four times as much as expected.

The Olympics are a bad deal for host cities. And they’re starting to take notice.

In 2013, when it bid for the 2020 Summer Games, Tokyo thought it would be spending $7.3 billion. By summer 2020, an Oxford economist told the Associated Press that Tokyo’s costs had already more than doubled to $15.84 billion. Local organizers have disputed that total — though they admitted in December 2019 that costs had risen to $12.6 billion. But competing estimates from a national audit board and national newspapers contend it could be nearly $30 billion.

To be sure, Tokyo is a special case. The city had to postpone the Games for a year after Covid-19 made hosting the international event a nonstarter, and they won’t receive the local tourism boom that usually accompanies the Olympics. But what happened in Tokyo is part of a larger trend — a 2020 paper by Oxford economist Bent Flyvbjerg found that “every Olympics since 1960 has run over budget, at an average of 172 percent in real terms, the highest overrun on record for any type of megaproject.” In other words, he found there’s something specifically wrong with the Olympics bidding process, even compared to other boondoggles.

And it’s not just the costs; some of the supposed benefits of hosting the Olympics have come under scrutiny by locals and economists alike. Economists Victor Matheson and Robert Baade outlined the potential benefits as “the short-run benefits of tourist spending during the Games; the long-run benefits of the ‘Olympic legacy’ which might include improvements in infrastructure and increased trade, foreign investment or tourism after the Games; and intangible benefits such as the ‘feel-good effect’ or civic pride.”

Like any major infrastructure project, the Games can provide a brief employment benefit and stimulative effect. But nowhere near what you might expect: “Overwhelmingly, the studies show actual economic impacts that are either near-zero or a fraction of that predicted prior to the event,” Matheson and Baade write.

And when it comes to the long-run economic benefits from improved infrastructure, they often don’t pan out. Those are usually attributed to the sports and general infrastructure that hosting the Olympics requires.

“There are 35 sports, most of which are fairly obscure, and many of which require very, very specific sports infrastructure,” Matheson told Vox. “So the problem is that most cities don’t have this on hand in the first place, and most cities don’t have much use for it afterwards.”

Matheson and Baade write that “Many of the venues from the Athens Games in 2004 have fallen into disrepair. Beijing’s iconic “Bird’s Nest” Stadium has rarely been used since 2008 and has been partially converted into apartments …” They add that there are potentially greater returns for general infrastructure improvements like transportation networks or increased hotel capacity, but it’s a mixed bag.

The intangible benefits are hard to quantify. To be sure, watching the Games is already a delight; doing so in real life — plus the excitement of having international attention on your city — is only more so.

And yet, that alone is a tough sell. It’s become abundantly clear that the financial cost of hosting the Olympics cannot be justified in economic terms.

What could reform look like?

Cities are taking notice of exorbitant costs that accompany hosting the Olympics and fewer and fewer bids are being made for upcoming games. In 2015, four of six bidders pulled out as countries bid for the 2022 Winter Games. In 2018, during bidding for the 2026 Winter Games, again four countries pulled out during the process, many citing local concerns about the financial commitments required.

Los Angeles was the only bid for the 1984 Summer Olympics, and its experience highlights one of the few ways a city can actually profit from hosting the Games. According to the Council on Foreign Relations, that was partly because LA, as the only bidder, was able to “negotiate exceptionally favorable terms with the IOC.” But “most importantly, LA was able to rely almost entirely on existing stadiums and other infrastructure rather than promise lavish new facilities to entice the IOC [International Olympic Committee] selection committee … [LA finished] with a $215 million operating surplus,” they write.

Following this success, the number of cities bidding trended up — which allowed the IOC to continue a process that encourages expensive plans. The overarching problem is that without reform, the incentives of the IOC and the local host city committee are misaligned. The former makes its money off ad revenue, while the latter needs to care about the exorbitant cost of infrastructure, local governance issues, and ticket sales (the latter of which became increasingly important for Tokyo).

Pacific University professor Jules Boykoff pilloried the IOC for running itself like a “profit-gobbling cartel” in a 2017 Los Angeles Times column:

For too long, the IOC has claimed that the city doesn’t have to build new infrastructure, that it’s the city’s decision. Of course host cities have to build new venues if they actually want to host the Games. Whitewater kayak venues don’t grow on trees.

In truth, the IOC chips in for operating costs by essentially laundering money from its lucrative corporate sponsorships and television-rights deals. That’s all well and good, but it’s time the organization stepped up and contributed to infrastructure costs as well.

Cost-sharing could incentivize the IOC to reduce its pressure for bids to contain more and more elaborate items. In an attempt to win a bid, “these cities started to offer so much more than what really benefited them,” University of Colorado Boulder economist Stephen Billings said. “I saw in Tokyo they built a specific venue for 3-vs.-3 basketball. … It seems like couldn’t we just use the regular basketball venue?”

Some have suggested a permanent location for the Olympics. Smith College economist Andrew Zimbalist laid out his case for this weeks before the Rio Olympics were set to begin and after more than 77,000 favela residents had been evicted: “Why not build the required 35 sports venues, the Olympic village and the broadcasting and media center only once, instead of building them anew in a different city every four years?” He suggests Los Angeles for the Summer Olympics, which he argues has all the necessary infrastructure that would not go to waste in between Games.

To ensure the benefits of the Games actually accrue and avoid the risks of internal political and economic strife, putting them in a location where the infrastructure is sure to be used and reused could address some of the downsides of hosting. And holding the Olympics in a wealthier country ensures that if there is some unforeseen financial cost to bear, the nation is better positioned to pay it. That might have its downsides too; excluding developing countries from the hosting duties is antithetical to the Games’ global mission (though the IOC has never awarded hosting to a truly low-income nation in the global south). But it’s worth considering.

As the Tokyo Olympics plays out in empty stadiums, the IOC will continue raking in profits from TV ad revenue as the world watches from home. But it’s the Japanese people who will inevitably foot the bill.

Author: Jerusalem Demsas

Read More