Democrats undershot it on the economy in 2009. They’re determined not to repeat that mistake.

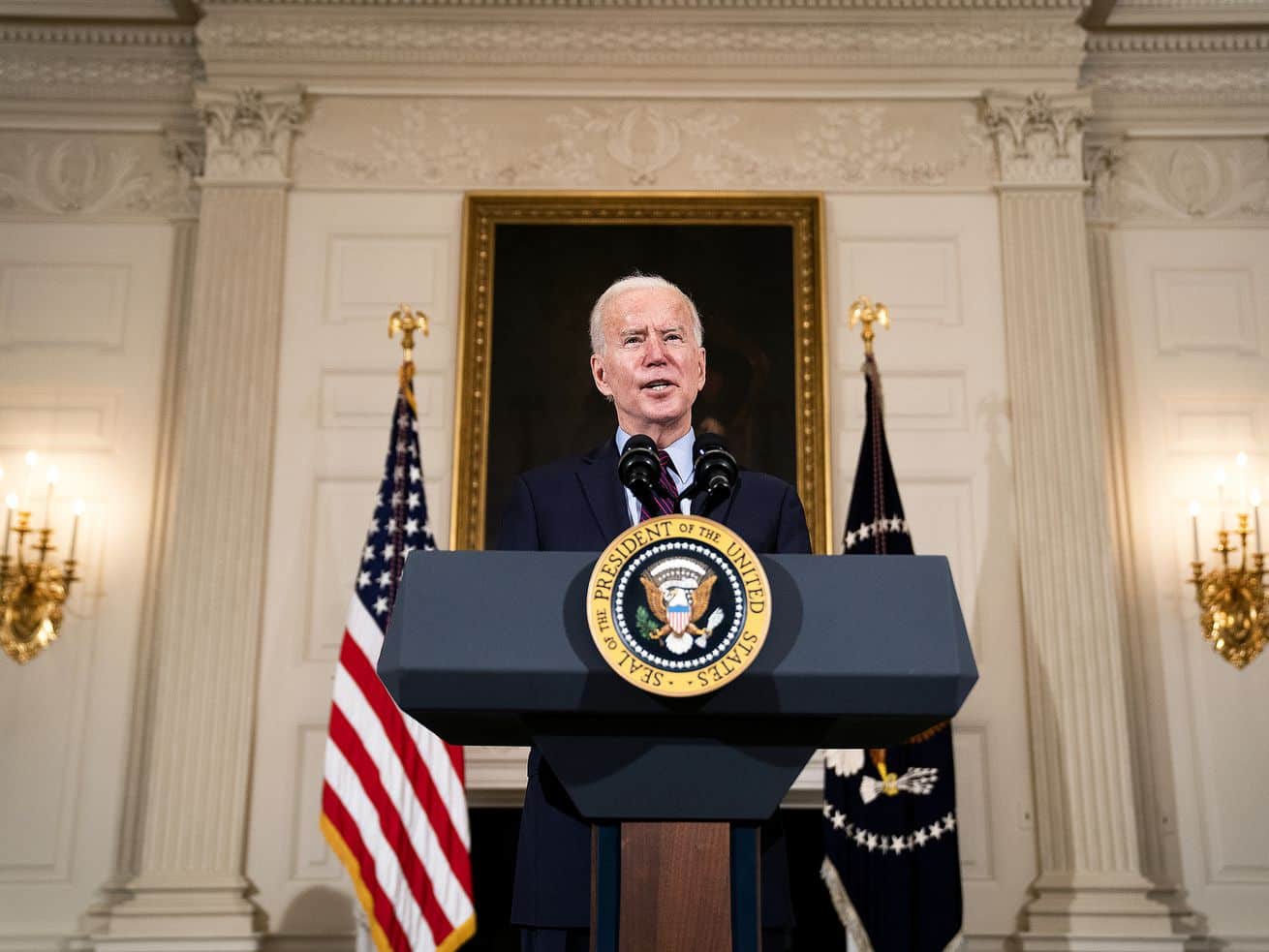

President Joe Biden appears ready to do what it takes to get the American economy back to full capacity — and then some.

Biden has proposed a $1.9 trillion Covid-19 relief package to help steer the economy through the pandemic, and he’s planning to propose a second spending package — one with an even heftier price tag — that invests heavily in infrastructure, climate, and caregiving. His administration is focusing on those most in need, and is even willing to run the economy a little hot for a while to get the gears churning.

“What gives me the most hope is that he’s given every indication of understanding the urgency of this moment,” Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-MA) told Vox in a recent interview. She said Americans are “asking for a government that steps up and helps deal with our health care problems, our economic problems, and our race problems.”

While unemployment levels have improved, Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell estimates the nation’s unemployment rate is still at 10 percent, a higher rate than the latest numbers from the Bureau of Labor Statistics suggest. “The pandemic has led to the largest 12-month decline in labor force participation since at least 1948,” Powell said in a speech last week. “We are still very far from a strong labor market whose benefits are broadly shared.”

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22301237/GettyImages_1229908224.jpg) Greg Nash/The Hill/Bloomberg/Getty Images

Greg Nash/The Hill/Bloomberg/Getty ImagesA Pew Research Center survey released last fall found that a quarter of American adults were struggling to pay their bills, while a third of people had dipped into their savings or retirement accounts to stay on top of bills. Black and Hispanic unemployment is still hovering at 9.2 percent and 8.6 percent, respectively. Where former President Barack Obama’s stimulus was meant to get the economy out of an immediate crisis, Biden’s goal is to get the economy to be more resilient to future downturns ,and to be more equal.

“Biden’s been very clear: To get back to where we were sets the bar way too low,” Jared Bernstein, who serves on Biden’s Council of Economic Advisers, told Vox last summer. “Much like FDR faced a structural crisis of economic insecurity, we’re at a similar place.”

This is all, on some level, surprising for a guy who ran as a moderate and was in the Senate for decades.

“Biden is a pre-neoliberal, and it shows,” said Felicia Wong, president and CEO of the progressive think tank the Roosevelt Institute. “He grew up in an era of the New Deal and the post-New Deal using government to shape sectors of the economy, not just using government to drive the macro-economy at some high level.”

To be sure, it’s still very early in Biden’s presidency, and whether his plans will remain as ambitious as they are now is an open question. The $1.9 trillion proposal could well be whittled down, and if and when some sort of rescue package passes, it’s unclear what the economic and political appetite will be for another big bill after this stimulus.

Biden’s plans don’t exactly sound like Bernie Sanders, but they also don’t sound like Bill Clinton, or even Barack Obama. Many of the issues he’s talking about, and the way he is talking about them, are decidedly different from the Democratic Party’s recent past.

It’s not quite post-neoliberalism, but it’s not not that.

Biden is walking into a historic moment that necessitates a historic approach

Biden, like many Democrats, appears well aware that Democrats undershot their response to the Great Recession — a mistake they’re determined not to make again. “We can’t do too much here,” the president told reporters in the Oval Office in early February. “We can do too little and sputter.”

“We have historic times with the pandemic, and that calls for a historically different approach,” said Betsey Stevenson, an economist at the University of Michigan and former member of the Council of Economic Advisers under Obama. “I think you see that in the Biden team.”

Some of what he and Democrats are backing are things born of a neoliberal legacy, such as the child tax credit (which some Republicans are also backing) and an earned income tax credit for low- to moderate-income workers. But they’re using other tools as well, such as procurement policy and proposed direct investment, to pursue their goals.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22301238/GettyImages_1301611517.jpg) Doug Mills/Getty Images

Doug Mills/Getty Images“The early signs do signal a more progressive economic policy, less willingness to be tripped up by debt fear-mongering, and a willingness to be more assertive in arguing that we need relief, we need some real strategic investments that will pay off, and we need to rebalance certain things in the economy in a pretty meaningful way,” said Aaron Sojourner, a labor economist at the University of Minnesota and former senior economist at the Council of Economic Advisers. “I don’t see a lot of early signals going in the other direction.”

There’s a very literal reason why Biden is saying not to worry so much about the deficit. Interest rates are very low right now, and the Fed says it plans to keep them that way, which gives Biden’s administration an opportune window for some heavy spending.

“Every major economist thinks we should be investing in deficit spending in order to generate economic growth,” Biden told reporters as he talked about his Covid-19 relief plan in early January.

As big as Biden’s current proposed Covid-19 relief plan is, it’s designed to be the springboard for an even larger recovery package that the president views as his signature piece of legislation.

“One of the ingrained lessons is that you have to go big enough when you can to fuel speeding to full employment, even if the size of the package is not easy politically or popular with everyone,” former Clinton and Obama economic adviser Gene Sperling said.

Current public polls show Biden doesn’t have too much to be worried about at the moment. The majority of the American public is on Biden’s side when it comes to passing a $1.9 trillion package; a recent CBS/YouGov poll found 83 percent of Americans support Congress passing another relief bill. That poll showed 39 percent of respondents thought the size of Biden’s bill was “about right,” while another 40 percent said it should be bigger.

“Making these types of investments in equity benefits everyone, it boosts the entire economy,” one administration official said on a call with reporters when discussing Biden’s equity executive order in January. “Equitable economic investments are not a zero-sum game.”

“They are rejecting this idea that there’s a trade-off, which has been a conventional frame for a long time,” Sojourner said.

Biden’s economic team is not quite Obama 2.0

One reason progressives might be feeling optimistic is some of the people Biden has hired. The president tapped Bharat Ramamurti as deputy director of the National Economic Council, Federal Trade Commissioner Rohit Chopra to head the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, and Wally Adeyemo as deputy treasury secretary. All three are Warren acolytes — Ramamurti is one of her longtime advisers, and Chopra and Adeyemo worked with her on setting up the CFPB.

“He is making some bold and progressive appointments, which is definitely a good sign,” said Darrick Hamilton, a professor of economics and urban policy and founding director of the Institute for the Study of Race, Stratification, and Political Economy at the New School.

Then there’s Biden’s White House Council of Economic Advisers. He named Heather Boushey, co-founder of the Washington Center for Equitable Growth, and Jared Bernstein, a progressive economist who advised Biden under the Obama administration. She has spent much of her career focused on inequality; he, on labor. Cecilia Rouse, Biden’s nominee to chair the Council of Economic Advisers, served in both the Clinton and Obama administrations and is in many ways a conventional choice. But if confirmed, she will be the first Black woman to hold that post, and she’s spent much of her career focusing on the labor force.

Neera Tanden, president of the Center for American Progress, was named head of the Office of Management and Budget. While she’s been known to get into it with lefties on Twitter and has come under some scrutiny over the think tank’s corporate ties, she’s also not known to be particularly concerned with deficits. Progressives have been pretty happy to see K. Sabeel Rahman, the former president of liberal think tank Demos, and Michael Linden, former executive director of progressive economic group the Groundwork Collaborative, brought on board at OMB.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22301270/GettyImages_1231079832.jpg) Andrew Harnik/AFP/Getty Images

Andrew Harnik/AFP/Getty ImagesThe administration is peppered throughout with people whose approaches and thinking are markedly to the left, even if they’re not the most visible. Janelle Jones, formerly of Groundwork Collaborative, has been brought on board as chief economist at the US Department of Labor. She is the architect of a framework called Black Women Best, based on the idea that centering Black women in politics and policymaking will lead to better economic outcomes for everyone. She has also argued in favor of the Federal Reserve targeting the Black unemployment rate in monetary policy. Danny Yagan, a former Berkeley economist, has been named chief economist at OMB. He’s done work on persistent lags in the workforce after the Great Recession.

Lindsay Owens, interim executive director of the Groundwork Collaborative, said it’s too early to tell how power dynamics will play out. “There is a strong group of progressive economic policy experts in critical positions throughout the administration,” she said. Having progressives in senior roles at OMB and CEA matters, she said, because people in those roles have, in some cases, been bottlenecks for more left-leaning proposals. “This shift doesn’t mean that they’re going to greenlight anything that progressives want, but it does mean that we’re not up against the type of gatekeeper that’s traditionally stymied our agenda. And that’s a real improvement.”

Still, plenty of Biden’s staff picks have given progressives something to grumble about. He gave Tom Vilsack yet another go as agriculture secretary; named Tony Blinken, whose consulting firm advised Blackstone and Boeing, as secretary of state; and tapped Brian Deese, a former Obama adviser who between government stints went to BlackRock, to head the National Economic Council. But other appointments have left progressives pretty pleased.

Hamilton is skeptical this departure from deficit hand-wringing will last too long. “[Biden] has expressed the values and talked about the need to not be confined by austerity politics as it relates to Covid-19. That’s all good, but we’ve got to get beyond austerity in general,” he said. “I have the feeling and the inclination that they will resort back to the responsible people in the room as it relates to implementation of a bold agenda, and back to the concerns around deficits and budgets.”

It is also a test for progressives. It doesn’t just matter that they’re in the room — it also matters that they get things done. “This time around, it’s safe to say that progressives were much more organized about appointments — personnel is policy, we all know — and it really made a difference. The challenge going forward is to be equally, if not better, organized around policy,” said Carter Dougherty, communications director of Americans for Financial Reform.

Biden learned from Obama’s too-small stimulus

One reason that Biden’s team is thinking a lot more liberally is that they saw how Democrats paid the price for a sluggish rescue plan to save America’s cratering economy and sinking stock market in 2009.

Looking back, many Obama White House officials — including some who are now running Biden’s White House — believe two things: They insist that the $800 billion stimulus Congress passed in February that year was the absolute maximum they could get at the time, and they also admit it was too small. A slow recovery meant Democrats suffered devastating electoral losses in the subsequent years, and they are determined to not repeat history.

The conventional wisdom at the time was that a $300 billion to $400 billion stimulus was more feasible. Most Obama officials felt that $800 billion was their absolute ceiling. “The [Senate] caucuses of 2009 and 2021 are nowhere near close to the same,” Obama’s former chief of staff Rahm Emanuel told Vox. “The public debate then was, ‘This is too much.’ Today, the debate is, ‘Is this enough?’”

Larry Summers, former director of Obama’s National Economic Council, told Vox, “Certainly we would have preferred more stimulus. We wanted a larger stimulus and we got as large a stimulus we could get through Congress. It was much more politically constrained.”

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22301248/GettyImages_84559700.jpg) Yuri Gripas/AFP/Getty Images

Yuri Gripas/AFP/Getty ImagesIn some ways, Obama having 57 Democratic votes in the Senate proved more of a handicap than the 51 votes Biden now has to work with. There was no real talk in Obama’s White House of using budget reconciliation on stimulus; the centrist Senate Democrat leading talks with Republicans, Sen. Ben Nelson (NE), wanted Republicans on board with the bill in order to vote for it. And Nelson was joined by a group of fiscally conservative Democrats from states like Arkansas, Montana, Kansas, and Louisiana, all mindful of not adding too much to the national debt.

“There’s been a substantial change in thinking,” Summers added. “The reality was different among many of the Democrats, you had a large number of people who had made their political career being alarmed about debt.”

Today, Democratic Sen. Joe Manchin (WV) is the Ben Nelson of the Senate, helming a bipartisan group that contains some of the same key players in Nelson’s. But Manchin’s red line doesn’t seem to be whether Republicans ultimately vote for the final bill. He and other centrist Democrats like Sen. Jon Tester (D-MT) seem content with the $1.9 trillion price tag on Biden’s plan, or something close to it.

There’s still a long way to go

While Biden’s administration is certainly more progressive than many administrations past, that doesn’t mean it’s some completely post-neoliberal apparatus, or that forces of neoliberalism and austerity aren’t still in play. The White House has already backed off of its proposed $15 minimum wage (it remains in the current version of Democrats’ Covid-19 relief bill, but it’s unclear if it will make it into final passage), and despite growing pressure from many Democrats in Congress to cancel some federal student debt through executive action, it remains unclear whether he will, given the complicated politics of the issue.

“There’s much further that progressives want the administration to push,” said Maurice BP-Weeks, co-executive director of the Action Center on Race and the Economy.

He pointed to the battle over who will head the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, a bureau under the Treasury Department that regulates national banks. In January, reports surfaced that Biden would tap Michael Barr, a former Treasury official under Obama. This sparked outcry from people on the left who have advocated for Mehrsa Baradaran, a University of California Irvine law professor who has written extensively about inequality in banking and the racial wealth gap. In an op-ed in the Appeal, Reps. Jamaal Bowman (D-NY) and Ayanna Pressley (D-MA) argued Baradaran “understands the inextricable link between the history of racism and banking in the United States and will protect historically marginalized communities from predatory financial practices and products.”

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22301249/GettyImages_1231126487.jpg) Eric Baradat/AFP/Getty Images

Eric Baradat/AFP/Getty ImagesBiden’s team has focused on diversity, but some critics note that his team is still quite white. “In terms of key economic policymaking goals, Biden has very few, if any, African Americans and Latinos in top roles, and that’s disappointing,” said Paul Thornell, former managing director for government affairs at Citigroup. “It is essential that the Biden-Harris team include more diverse people in these critical roles who have demonstrated expertise and experience on issues of importance to communities of color.”

To be sure, Rouse, Biden’s nominee to head the CEA, and Susan Rice, the former national security adviser under Obama who is now director of Biden’s domestic policy council, are Black. Biden is also reportedly considering Lisa Cook for an open Federal Reserve Board seat; she would be the first Black woman appointed to the Fed.

It’s still very early in the Biden administration, and there are countless fights still to play out. But at least for now, the approach seems to have some significant breaks from the past.

Author: Emily Stewart

Read More