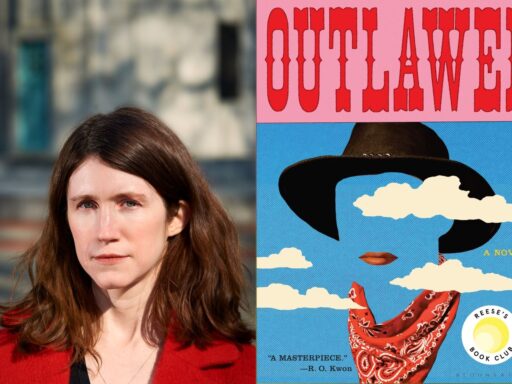

Vox gender reporter Anna North talks about rewriting the myth of the American Western in her new novel Outlawed.

Less than two weeks into its run, 2021 is already a year that could use a little joy. Here to provide some is the scrappy new feminist Western novel Outlawed by Vox gender reporter Anna North, which has been announced as a Reese’s Book Club pick. It’s an absolute romp and contains basically everything I want in a book: witchy nuns, heists, a marriage of convenience, and a midwife trying to build a bomb out of horse dung.

Set in an alternate version of the Old West in which America’s sexual morality has shifted to prioritize fertility rather than chastity, Outlawed tells the tale of a group of hardscrabble gender non-conforming outlaws and their standoff at the legendary Hole-in-the-Wall. In real life, the Hole-in-the-Wall is a mountain pass in Wyoming where some of America’s most notorious outlaws made their camp — but in Outlawed, those outlaws are now people who have failed to abide by America’s strict new sexual fertility laws. As a result, they’ve been accused of witchcraft and had to flee for their lives.

At the center of the story are Ada, a young midwife who has to flee her home town after failing to have a child two years into her marriage, and the enigmatic Kid, a nonbinary outlaw who built the Hole-in-the-Wall Gang from the ground up. Together, Ada and the Kid have to fight against the law (slash also the patriarchy) while holding out hope for a better world.

Back when offices were a thing, I used to sit next to Anna, and I can confirm that she spent her days hard at work reporting and not casually composing buzzy new novels on the company dime. So I called her up to find out more about how she managed to pull off this heist, and about what it takes to make the Old West feel new again. A transcript of our conversation, lightly edited for length and clarity, is below.

Let’s start with the alternate history stuff. Talk me through the process of developing this new version of the Old West.

That was one of the most labor-intensive things about the book. Because even though I knew it’s not going to be the real history — and that was important to me, that this doesn’t actually exist in our world — I still felt like I needed to know a lot about the real history to know what would be possible, or how I would want to deviate from it.

So I did a ton of reading. A lot of reading about indigenous history in the Americas. A lot of reading about outlaws. I read some books specifically about the Hole-in-the-Wall Gang and outlaw history in Wyoming and in the West, and then some about Black Americans in the West. Nell Painter’s Exodusters was really just incredibly helpful in terms of teaching me history that I didn’t know a lot about before I went in.

With all that research, not every part of it made it on the page in a literal way. But once I had done a lot of reading, then I felt like I had this foundation. I had a better sense of what really happened. I had a basis to work from.

One thing that interests me about this premise is you’re taking this sort of Handmaid’s Tale-esque idea of an America governed by fertility laws, and then you’re placing it in the past rather than making it a near-future dystopia. How do you think putting that idea into an alternate history rather than the immediate present changes the way it plays out?

I will tell you, in a very early draft, I actually set this in 1950. But everything was the same. The idea was that there’s this flu pandemic, which obviously felt less immediately relevant at the time I was writing it than it does now. But that happens in 1830, and then from that point on, American history diverges. So in this very early draft, certain things just stayed slower, and so 1950 looked in certain ways like 1893 or 1894 would look.

I can’t remember if it was my agent or my editor or other early readers, but they were like, “This is confusing. It’s just a lot to take in. It’s an alternate history. It’s 1950. It looks like the 1890s. There are outlaws. What’s happening?”

I think at that point I realized that there’s no need for readers to have to understand all this about the pace of technological advance. I could just set this in an alternate 1894, 1893, and we’re still working with an alternate history, but it’s not quite the conceptual lift for the reader.

I never wanted the book to be a one-to-one allegory for contemporary America. I did want it to play with ideas of genre and also be a fun story. And I think in some ways setting it in the past helps with that, and helps hopefully take the pressure off of it to be like, “This is 100 percent a commentary on where we are now.”

Ada has so much medical knowledge, and her acumen as a midwife feels really grounded. How much of that is accurate to 19th-century medicine?

A lot of it. I did a fair amount of research on midwifery and on the history of gynecology in the history of medicine to find out when various things were discovered. When did people start doing various things? What treatments would midwives use? Even though, again, this is an alternate world, I tried not to diverge too much from what a midwife of the era might have known or done.

I kind of became obsessed with midwifery while I was writing this, and also just for my work at Vox covering reproductive justice issues. That comes up more and more, and so I kept doing reading about it after I was mostly done with this book.

There’s a really interesting book called A Midwife’s Tale, and it’s this intensely detailed diary of a midwife in New England in early America. It’s just so fascinating, because she gives an incredible breadth of care. She’s delivering babies, and she’s delivering an enormous majority of the babies. Like there’s a doctor, one guy who lives nearby, and he delivers like one baby in the time she delivers 80 or something like that. Mostly they don’t call him until after they call her.

But she’s also ministering to people who have the flu. She’s going to people who have all manner of contagious diseases. She’s treating almost every ailment that a family could have.

And she’s doing other stuff. She’s selling textiles, doing all this business on the side. She’s brokering marriages among her family. She testifies in court at one point. It’s just this really fascinating window into the life of this practitioner, and a reminder of how crucial midwives were to communities for centuries and centuries, until the rise of the American Medical Association. They get marginalized after that.

I want to turn here to the Hole-in-the-Wall Gang. I love the way the Hole-in-the-Wall works as this sort of Shakespearean greenwood, with all of the conventions of gender and race and class becoming a subject of play rather than restrictions. There’s an amazing scene when Ada arrives at the camp and everyone is draped in flowers and singing that song from Twelfth Night. So how did you go about developing that sense of place while still making it feel specific to the Old West?

I hadn’t even 100 percent thought about that as a Shakespearean greenwood, although I did put in the song from Twelfth Night, and certainly there’s a lot of gender play in Twelfth Night and all those comedies. Those have always been some of my favorites, so certainly influence just trickles in all the time.

Creating this setting really started when I went there [to the Hole-in-the-Wall]. That was probably the biggest thing. I was really lucky to be able to do this. It was right before I started at Vox [in 2017], and for the first time in my life, I took three weeks off work.

My husband and I went there and we drove around. I went to the site of the actual Hole-in-the-Wall camp, because the Hole-in-the-Wall Gang were real. They were real outlaws, and women were part of the gang too. It wasn’t just men. I went to where they had their buildings and then drove around that valley and went to the actual hole in the wall, which is the lookout point for which the valley is named, and for which the gang is named. It’s actually a little hard to see. It’s not visually striking. It’s very beautiful, but it’s not like, “Oh, there’s the hole.” You kind of have to pick it out.

But I think that was really step one. I couldn’t really ground any of these characters or figure out what they should be wearing or eating or doing, even, until I had a sense of that place.

One of the biggest influences on the book is the Krazy Kat comics. I was reading those a lot when I was first starting to work on this. Those are Westerns, and they’re set in Arizona. They’re animals, so obviously it’s a cartoon. It’s very fictionalized. It’s funny to even call it fictionalized. But it’s also this really interesting space of gender play. Krazy Kat uses different gender pronouns at different times. This is something that [the author of the comics,] George Herriman, talked about. There’s a really good Gabrielle Bellot essay that talks both about gender fluidity and Krazy Kat, and then also about George Herriman himself and his own racial identity and how that influenced Krazy Kat, too. Everybody should read this essay!

From Krazy Kat, and some other stuff too, I was trying throughout to find a balance. There are very serious issues in this book, but also a sense of play and fun and a sense of joy. The characters are in dark circumstances and there’s danger. But I mean, the scene you mentioned where they’re draped in flowers, they’re dancing, they’re singing — I wanted to have that be a part of the book, too.

I wanted to also talk a little about the historical Hole-in-the-Wall Gang, and I think especially Billy the Kid. You have a fantastic riff on him with the character of the Kid. How do you think about the relationship between your outlaws and their historical counterparts?

So first of all, there were at least two outlaws, probably more, who went by the Kid. There’s Billy the Kid, and then there’s the Sundance Kid from Butch Cassidy. I feel like maybe they even knew Billy the Kid. I’d have to double-check that. Jesse James was definitely affiliated with the Hole-in-the-Wall Gang. This isn’t a very long era, when the outlaws who are famous to Americans were swashbuckling around. It’s not a very long period, and so the people that you know of, often they know each other.

It comes down to play. The Hole-in-the-Wall Gang were real people. Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid were real people. They did real crimes. But they’re also part of our national mythos. And that’s what I wanted to play with.

What happens if the myth is a little different? What would it look like if this outlaw gang of Western lore looked a little different than it does — in some of our histories, I should say. There’s a big tradition now of doing this, not necessarily with outlaws.

After I had finished the book, because I tried really hard not to read any Westerns while I was writing it, I was looking back, like, what have I missed? There’s been a big movement to look at this myth of the Western, and to be like, “What did it leave out?” I keep bringing up How Much of These Hills Is Gold because it’s a wonderful book. It’s not about Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, but there are outlaw tropes in it. It’s about the gold rush, and it’s got a family that includes people who are immigrants, and what that means.

There’s a larger tradition right now examining, “What does the American history that some of us were taught in school leave out?” And I think fiction writers are starting to do that, too, in really interesting ways. Ever since I finished the book, I’ve been blown away by this cool emerging tradition that I didn’t even necessarily know about when I was writing.

This is kind of a selfish question, but I am so curious: How did you find time to write a whole novel while also being a reporter and doing tons of work there, and also having a small child? Like, do you sleep?

Part of the key is I wrote almost all of this before I had my son. I started it before I got pregnant and then was working on it while I was pregnant. Then, obviously, there was a lot of urgency. I was like, “I’ve really got to get this done, and it’s closing in on the ninth month.”

I was really close. I was like, “I probably only have like a week more work.” And then he was born a week early! So that part took me the next six months, just about.

Wow, how inconvenient of him!

I know. I mean he’s very cute, but everything is way slower, obviously. But it’s also been really interesting. I had him when I was finishing up and when I was doing edits, and that informed a lot of the book, too. Especially the stuff about pregnancy or not-pregnancy. But talk to me in five years and see if I’ve gotten anything else done!

To some degree, it’s an effort of compartmentalization. I try to have a different brain space when I’m doing fiction. I used to do it in a different physical space, but I don’t go to different physical spaces very often these days.

But more and more, the journalistic work and fiction work complement each other. Especially the stuff I already knew about reproductive health and reproductive justice and midwifery was really helpful in this book. So in that way I’m glad that these two careers could dovetail a little bit.

Author: Constance Grady

Read More