Gov. Mike DeWine tested positive (and then negative) for Covid-19, but his state is doing “okay” suppressing the virus.

This week, it seemed as if Ohio’s coronavirus outbreak had reached Gov. Mike DeWine.

It was reported on Thursday morning that DeWine, who was supposed to meet with President Donald Trump later that day in Cleveland, had tested positive for Covid-19. He would stay home and get tested again, rather than accompany the president.

But then came the follow-up story on Thursday evening: A second test on DeWine was negative. He may never have been sick at all.

The whole thing was a little confusing and opaque — not a bad analogy, actually, to explain the state of Ohio’s outbreak. Early on in the pandemic, DeWine’s considerate public health approach was often contrasted with the Trump administration’s more bulldozing strategy. He was one of a handful of Republican governors — along with Maryland’s Larry Hogan and Massachusetts’s Charlie Baker — who faced outbreaks in the spring and appeared to take the threat seriously.

Today, Ohio is faring better than the summer’s worst hot spots. But the situation still isn’t ideal.

First, though, to clear things up on DeWine: The different results could be explained by the two different tests he took. The initial positive was from what’s called an antigen test: It can give results within minutes, by looking for certain proteins, but is generally less accurate than a diagnostic test that detects the virus’s genetic material. That kind of test, called a PCR test, was what DeWine took the second time, and it came back negative. So it seems plausible, if not certain, that DeWine’s first test was a false positive from the less accurate antigen test. DeWine and his wife were going to be tested again on Friday.

But really, that bizarre turn of events is just an excuse to explore the Covid-19 outbreak in DeWine’s home state (and mine), a focal point in the spring that has been overshadowed by the Arizona-California-Florida-Texas cohort.

Ohio is doing okay on Covid-19 compared to other states

After talking with some Ohio-based public health experts and looking at the data, Ohio’s current situation would best be described as “okay” — which was the take from Sara Paton, an epidemiologist at Wright State University.

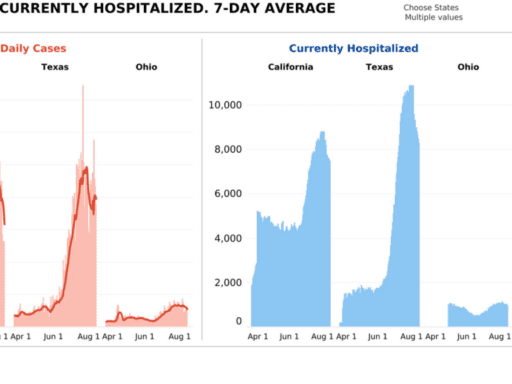

The state experienced a second wave of infections starting in late June and continuing through July. On June 1, there were 439 new cases reported; on July 1, there were 1,307. The state appears to have peaked on July 13 with 1,715 new cases. Ohio’s surge coincided with those in other states, but its outbreak hasn’t swelled to the same degree as those of some other large states.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/21708912/3SC_Pos_Hos__1_.png) Covid Tracking Project

Covid Tracking Project

Cases are more concentrated in the state’s three biggest cities — Cincinnati, Cleveland, and Columbus — leading to some of the same racial disparities seen elsewhere in the country. Black people are 13 percent of Ohio’s population but they make up 25 percent of Covid-19 cases and 19 percent of Ohio’s 3,618 deaths. As in most other states, nursing homes have suffered greatly, with long-term care facilities accounting for more than half of the fatalities.

But things are looking better. The number of daily new cases in Ohio has now dropped below 1,000 for more than a week. According to the Covid Exit Strategy dashboard, cases were down 17 percent over the past two weeks, and hospitalizations have dipped as well.

One measure of an outbreak’s saturation in a state, new cases per million people, bodes well for Ohio: It ranks in the bottom third of states, with 96. That’s still above the targets experts have set for states that want to safely reopen businesses and schools, but it’s better than most.

“I’m hopeful that those trends reflect people realizing that things aren’t normal and have gone back to taking precautions — like wearing masks,” William Miller, an epidemiologist at Ohio State University, told me.

One question that always arises when examining a state’s Covid-19 data: How well are they actually surveilling for the disease? On that front, Ohio is again doing better than most other states, even if its performance isn’t really exemplary based on the standards set by public health experts. For example, its positive test rate is down slightly to 5.2 percent; that is better than 30-some other states but a little above the target set by experts (5 percent or, preferably, less) for confidence that a state is catching most cases.

In Ohio, as in most places, getting timely test results has sometimes been a struggle. Local health officials in southwestern Ohio were recently reporting up to two-week delays. That is far too long from a public health perspective: Officials want results quickly so they can ask the infected person and anybody they have recently come into close contact with to isolate themselves so they don’t spread the virus to other people.

“Even areas with a low number of cases are more likely to be problematic if testing rates and timely results are low,” Zelalem Haile, an Ohio University epidemiologist, told me. “In such areas, the spread can be as high, and many cases will remain undetected.”

Still, across all of these metrics, Ohio looks better than the summer’s trouble spots. Texas and Arizona have triple its positive test rates. Florida has three times as many new cases per million people.

And Ohio’s outbreak appears to be plateauing, with no evidence of the kind of acceleration we’ve seen in Alabama and Mississippi, two new hot spots identified by experts.

DeWine has been an example of responsible Republican leadership

There are a few explanations for Ohio’s relatively stable coronavirus status quo, experts say. Some of them are structural, like lower population density and a high number of hospital beds per capita. Though at this point the virus has reached all 88 of Ohio’s counties, it can still be harder for an airborne virus to spread where people are more spaced out.

But experts also credited DeWine’s pandemic response and Ohioans’ willingness to adhere to social distancing guidance and wear masks. That has suppressed spread and allowed the state’s health system to handle the Covid-19 caseload.

The Ohio Hospital Association told me it developed surge capacity plans for the three major cities in cooperation with the state government, but they haven’t been needed yet. DeWine also deployed the state’s protective equipment stockpile in June, and hospitals did not report supply shortages during the recent spike in cases, the association said.

“He uses data and science for his decisions,” Paton said, “and is pretty transparent on what he is doing and why.”

The differences between DeWine, who was wearing a mask back in the spring, and Trump, who didn’t wear one until July, have been frequently drawn. The New York Times reported in April on DeWine’s “split from Trump” in the pandemic and the public’s rising approval of the governor.

That doesn’t mean Ohio’s response has been free from any problems or controversy. One Ohio prison had such a bad outbreak, there were more coronavirus cases than its supposed inmate occupancy, as ProPublica reported. DeWine got locked in a chaotic legal battle while trying to postpone the state’s primary elections in March. His top public health adviser, Amy Acton, stepped down in June after she was targeted by activists who opposed the state’s stay-at-home order.

But even there, the discord was between DeWine’s more cautious approach and the desire of conservative activists, much like Trump’s, to reopen the economy as soon as possible in an election year. The governor has allowed businesses to reopen with some restrictions, but he also issued a statewide mask order on July 23, earlier than the Democratic governors in Minnesota and Wisconsin.

“The reopening was inevitable. I believe the decision to reopen was based on evidence of adherence to the recommended guidelines by Ohioans,” Haile said. “Cases were far less than what was expected or projected from various models, which is another indication that guidelines were being followed allowing the curve to flatten.”

But in Ohio, as elsewhere, complacency poses a threat. Paton pointed out that social contacts in the state, as measured by the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation at the University of Washington, are not down as much as they have been in California, Florida, or Texas, which have been in more of a crisis mode than Ohio over the past month.

All it takes is a superspreader event or two for new hot spots to flare up and then spread could rapidly accelerate. The state may struggle with containing new outbreaks; NPR reported last month that Ohio had not hired enough contact tracing workers based on its estimated need to track Covid-19.

“Masks are only part of the solution. It would help Ohio more if people would social distance more. DeWine has made this point many times on his press conferences,” Paton said. “There have been a lot of Covid outbreaks in Ohio due to backyard barbecues, weddings, funerals, etc.”

So Ohio still has work to do. The virus certainly isn’t suppressed yet. The situation, like DeWine’s test results, is fraught and unpredictable.

But the governor’s leadership has put the state in a better position to succeed than most others. The public would seem to agree. Based on the polling, the Washington Post’s Amber Phillips wrote last week: “He’s now one of the most popular governors in America.”

Support Vox’s explanatory journalism

Every day at Vox, we aim to answer your most important questions and provide you, and our audience around the world, with information that has the power to save lives. Our mission has never been more vital than it is in this moment: to empower you through understanding. Vox’s work is reaching more people than ever, but our distinctive brand of explanatory journalism takes resources — particularly during a pandemic and an economic downturn. Your financial contribution will not constitute a donation, but it will enable our staff to continue to offer free articles, videos, and podcasts at the quality and volume that this moment requires. Please consider making a contribution to Vox today.

Author: Dylan Scott

Read More