“Any one of us could unknowingly be a superspreader.”

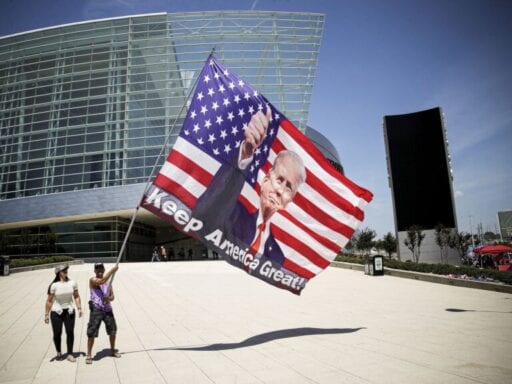

This Saturday, thousands of people are expected to gather inside the BOK Center in Tulsa, Oklahoma, a city where Covid-19 cases have risen steeply since May 31, at a rally for President Donald Trump’s reelection campaign. There may not be room for physical distancing in the arena, which can hold 19,000 people. Each person who registered has signed a waiver to say they will not sue Trump if they get sick with Covid-19.

The city’s top health department official has warned that a large indoor gathering like this in the midst of a pandemic is unsafe. The organizers have promised to hand out masks, but people aren’t required to wear them. They plan to screen people for fevers at the door, but that will likely miss asymptomatic people who are infected but not feeling sick.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/20042954/Screen_Shot_2020_06_18_at_8.19.29_PM.png) Tulsa Health Department

Tulsa Health DepartmentGiven that this coronavirus tends to spread when people are in close, indoor quarters for extended periods, there is a very real risk this rally will turn into a massive “superspreading event,” where many attendees — and people they later come into contact with — will be infected.

On average, people with the coronavirus infect about two other people; most pass the virus to just one other person, or to no one else at all.

But some people go on to infect many more — often before they even get symptoms. Many of these transmission chains begin with superspreading events, where one person (usually in a crowded indoor space) passes the virus to dozens of others. Early contact tracing studies suggest these events have been a large driver of transmission around the world. By some estimates, 10 percent of people have been causing 80 percent of new infections.

Some of the largest superspreading events have happened aboard ships, including Navy carriers and cruise ships. But they are also happening on the ground in smaller settings, including at a church in Arkansas.

In early March, a 57-year-old pastor and his wife, who both felt fine, attended a series of church events over three days, and the pastor returned for an additional Bible study group a few days later. Soon after, they each started developing symptoms and eventually tested positive for the coronavirus. But it had already spread. At least 33 of the other 92 event attendees later tested positive for Covid-19, and three of them died. These cases then spawned more than two dozen other illnesses — and another death — in the community.

A recent preliminary Centers for Disease Control and Prevention report analyzed all of the 3,184 confirmed Covid-19 cases in Japan through the beginning of April. The researchers found that 61 percent of cases could be definitively traced to clusters of spread outside the household, such as at restaurants, bars, event venues, and workplaces. And this is likely an undercount due to limitations in contact tracing.

What causes these superspreading clusters, and why are they such a key driver of this pandemic? Is it something about the people themselves who start them? Or is it more about the settings where these events take place? Or a combination?

Thankfully, we are learning more about superspreading events, and this insight can help dramatically slow the spread of the coronavirus, and save lives — all while potentially allowing more people to return to less risky activities. That is, if policymakers implement the guidance, and people follow it. “If you could reduce superspreading, you could have a massive impact on the pandemic,” Elizabeth McGraw, director of the Center for Infectious Disease Dynamics at The Pennsylvania State University, told Vox in an email. Let’s walk through it.

Why is the coronavirus so good at superspreading?

To understand what might kick off a superspreading event, let’s review some basics about how this virus, SARS-CoV-2, spreads. Researchers have found that it often spreads through microscopic droplets created when an infected person coughs or sneezes — or even speaks — and another person breathes them in. These disease-containing droplets are a large part of the reasoning behind staying at least 6 feet away from people and wearing a mask in public.

But scientists are finding that the virus likely also spreads through even tinier, longer-lasting particles from breathing or speaking (or flushing a toilet) called aerosols. These are so small they can linger in the air after an infectious person has left — and may contain infectious virus particles for up to three hours. And they may be a key element to superspreading events: An infected person could seed a poorly ventilated indoor space with virus without even getting physically close to all the people they end up infecting.

Superspreading also appears to be more likely with SARS-CoV-2 because people typically have the highest level of the virus in their system (making them infectious) right before they develop symptoms. (This is very different from other severe coronaviruses like SARS and MERS, where people were most infectious seven to 10 days after they started feeling sick, when they were more likely to be in isolation or in medical care.) So thousands of people with active Covid-19 infections continue to go about their lives not knowing that they could be spreading the disease.

This has meant that, as some researchers noted in a preprint, “most transmissions are front-loaded” toward the beginning of the illness. As another team of researchers who analyzed cases and contacts in Taiwan noted in JAMA, people actually had a much lower risk of spreading the virus after five days of symptoms. This might be in part because sick people are less likely to go out, whether because they don’t want to spread their illness or because they simply don’t feel up to it.

But it also has to do with a person’s “viral load” — an amount that actually tends to go down as symptoms wear on. A May study of samples collected from patients, published in Clinical Infectious Disease, suggests that people who had symptoms for more than eight days might not actually be very infectious.

All of this makes it so much more likely for people to be spreading the virus — sometimes to very large groups of people — unwittingly.

“I think the virus’s biggest weapon has been that it can be spread by asymptomatic or presymptomatic people,” McGraw says. “This, in combination with insufficient testing of people in the community, has meant that it can move from one host to the next while we are unaware.”

This coronavirus’s uneven spread is calculated by its “dispersion factor” (sometimes abbreviated as “k”): what proportion of cases cause the bulk of transmissions. An even dispersion rate would mean most people cause the same number of secondary infections.

We still don’t have an entirely firm k factor for Covid-19, and a lot of the research is still in the prepublication phase and has not been peer-reviewed. But preliminary estimates, such as one co-authored by Adam Kucharski, an infectious disease dynamics expert at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, suggest that about 10 percent of infected people cause about 80 percent of the virus’s spread.

Another early, non-peer-reviewed study from Israel put the local k factor at between 1 and 10 percent of infected people causing 80 percent of new infections. And a preliminary analysis of superspreading events in Hong Kong put their estimates at around 20 percent of infections causing 80 percent of local transmission.

All of this shows how important superspreading events have been in the virus’s spread. But it doesn’t fully explain why they are happening — or how to stop them.

Are certain people more likely to be superspreaders?

Scientists are learning that a person’s likelihood of kicking off a superspreading event probably depends a little bit on biology and a lot on behavior.

Some individuals seem to develop higher amounts of the virus in their system, upping their odds of transmitting it to others.

And given that the amount of virus in the body tends to shift over the duration of infection — rising until around the onset of symptoms, then declining — the chance that someone is a likely superspreader changes over time.

Finding out whether some people are predisposed to be superspreaders will take more time and research, McGraw says.

But what we have been learning is how individuals’ behavior could increase the chance they spread the virus to many others — or not. “We do know that wearing masks, keeping up physical distancing, avoiding crowds, and isolating upon becoming sick or testing positive can prevent superspreading,” she says.

The new CDC report out of Japan found 22 people who likely started clusters of cases. (Half of them were 20 to 39 years old.) And for 16 people, the research team could figure out when transmission occurred, which is important because it showed that 41 percent of them didn’t have any symptoms when they spread the virus. In fact, of the superspreaders, only one had a cough when they infected others.

This points to an important nuance in thinking about how some individuals might be sickening a disproportionate number of others. “We should not think about superspreaders as villains,” McGraw says. “Any one of us could unknowingly be a superspreader” — especially given what we know about how much it spreads when people are feeling just fine.

But that means we can probably also avoid becoming a superspreader. How? By doing things we already know can limit the spread of the virus: “Wear a mask. Wash your hands. Keep your distance, and respect the physical space of others,” McGraw says.

As the pandemic has worn on and become increasingly politicized, many people in the US are now resisting continued precautions, leading to mask rebellions, large gatherings — and much greater chances of new superspreading events. The upcoming Trump campaign rally in Tulsa is just the latest and largest example. As the top public health official there said in a press conference Wednesday, “I know so many people are over Covid, but Covid is not over.” And indeed, according to Covid Exit Strategy, Oklahoma’s new daily cases are up 125 percent over the past 14 days.

“I see an increasing number of people not wearing masks in public as restrictions ease,” McGraw says. “I find it disappointing. I worry that our focus on personal freedoms in the US, rather than being more community-minded, is going to prolong the outbreak and lead to more deaths than necessary.”

Why superspreading is more common at concerts than in libraries

Although we know that individuals’ behavior plays a role in superspreading, what might be even more important for these events is where they happen.

Researchers have been tracking many superspreading events around the globe, and there seem to be recurring locations no matter what the country. In addition to those we have heard most about, like prisons, food processing plants, and elder care facilities, there have also been numerous large superspreading events at bars, churches, offices, gyms, and shopping centers.

These are also places, though, that are now reopening around the country and likely contributing to the upward swing of cases in many states. As Kucharski notes, “Identifying and reducing risky events and environments could make a substantial dent in transmission.” Not reducing these events has the opposite effect on the number of cases.

For example, as South Korea started to reopen in early May, one infected person who attended five nightclubs caused at least 50 new infections.

And a preliminary study of infection clusters in Hong Kong found that the largest one documented so far, which resulted in 106 Covid-19 cases, was linked back to exposures from staff and musicians at a series of bars. Seventy-three of the people in this cluster caught the virus at the bars (including 39 who were customers), who then spread it to others in the community.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/20042338/Social_spreading.png) Epidemiology

EpidemiologyA team of researchers at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine has been collecting data on these superspreading events in a public database. The largest ones — including two that resulted in more than 1,000 cases each — happened aboard ships. Hundreds of cases also have originated from single individuals in close contact with others in worker dormitories, food processing plants, prisons, and elder care facilities.

But next on the list are an outbreak tied to a single person at an indoor-outdoor shopping market in Peru who likely infected 163 other people; an indoor-outdoor religious service in India where one person likely sickened 130 others; and an indoor-outdoor wedding in New Zealand where a single case sparked 98 more.

Only one of the 22 cluster location types the team analyzed in a preliminary study was an outdoor setting (building sites in Singapore; four clusters were linked to these sites, causing a total of 95 infections acquired directly from the sites).

These findings line up with other preliminary research that calculated closed environments to be almost 20 times more likely to spur additional coronavirus infections than open-air ones.

It’s not just being indoors that seems to matter. There are other reasons certain venues are more prone to superspreading.

As we’ve learned from studying events, like the infamous March church choir practice in Skagit County, Washington, during which one person infected an estimated 52 of 61 people (two of whom died), loud talking and singing “can spread more virus than talking at a normal volume,” McGraw says.

Indeed, the recent analysis out of Japan found that “many Covid-19 clusters were associated with heavy breathing in close proximity, such as singing at karaoke parties, cheering at clubs, having conversations in bars, and exercising in gymnasiums.”

Even looking more closely at cases from these locations can give us clues about what makes superspreading more likely. A CDC report from South Korea detailed 112 new Covid-19 infections that came from aerobic dance classes (like Zumba) in one city. Interestingly, an instructor who infected dance class participants also taught yoga and Pilates classes, but none of those participants got ill.

“We hypothesize that the lower intensity of pilates and yoga did not cause the same transmission effects as those more intense fitness dance classes,” the authors noted. “The moist, warm atmosphere in a sports facility coupled with turbulent air flow generated by intense physical exercise can cause more dense transmission of isolated droplets,” thereby making the virus more likely to spread.

These hubs of contagion also are helping us learn what activities might be safer, like seeing small groups of people, from a distance, outdoors.

“There’s increasing evidence that certain environments, like socially distanced picnics with a few other people, are far less risky than crowded, close-knit interactions, like large gatherings indoors,” says Kucharski, who is also the author of a forthcoming book called The Rules of Contagion.

What should we be doing to limit superspreading?

Superspreading can be both a curse and a potential blessing in a disease outbreak. It means that having everyone on full lockdown is not necessarily essential to keep the disease in check when it is not already circulating widely in a community — if (and that’s an important “if”) we can determine the highest risks for superspreading and prevent them. That’s the blessing. The curse, Kucharski says, is “if risky situations are missed or undetected, it means transmission could persist.”

Not only that, but there is also the danger that, as the authors of the one early report note, “If a superspreader is infected, the disease may spread to other superspreaders.” This seems entirely possible, especially given that people surrounding an original superspreader were probably already engaging in behavior (like attending a crowded public location) that would make them more likely to be a superspreader, too.

Superspreading events also can strain other systems in place, like contact tracing, to contain the virus, increasing the odds that further infections will continue to spiral in the community. Just as a sudden spike in cases can surpass the capacity of health care systems, a big jump can also surpass local capacity to track and notify contacts of the infected to isolate and get tested.

But now that we have data from recent superspreading events, we could theoretically prevent future ones.

The good news is that the science suggests we can. But it depends on government, businesses, and individuals to put these lessons into practice.

For example, in addition to physical distancing measures, limits on capacity, and requiring mask-wearing, governments and businesses could also take into account other details we are learning about superspreading events, like loud environments that encourage more droplet-filled speech. For example, as Colorado shifts to allow bars to open and indoor events to take place this weekend, it could establish guidelines to limit noise levels (by, for example, not allowing loud music) so that people don’t need to yell or talk loudly.

Some current efforts to prevent superspreading — like taking people’s temperature before they enter a building — are not failproof, however.

Even if a business, day care, or large-scale event checks everyone’s temperature before they enter, “it won’t necessarily pick up everyone who is infectious,” Kucharski says.

McGraw agrees, noting that it “is really only going to catch a subset of people” who have the virus. For example, some infected individuals never develop a fever, or “their fever rises and falls over a single day” or changes through the illness, she says.

One company that has tested more than 30,000 people for Covid-19 recently reported that just 12 percent of people with positive tests had a fever of 100 degrees or higher. And only 37 percent even had a cough.

NEW results out of San Francisco. @Color tested 30,000 people who signed up. About 300 (1.3%) were positive. Out of those:

-30% asymptomatic when tested

-37% cough

-32% headache

-12% feverTHUS:Screening for a fever at workplaces, restaurants, airports isn’t very effective (1/2)

— Amy Maxmen (@amymaxmen) June 16, 2020

One thing that will help reduce these events is more contact tracing and testing. These tools would also help us learn more about the nuances of superspreading and prevent more of it in the future. If those 10 or 20 percent of people who would have sparked 80 percent of the new infections instead only passed the illness on to one or two other people, we could be in a much different place, and soon.

A first step is following the lead of infectious disease experts, who know well what potential superspreading situations to avoid. McGraw says, “Right now, I would not go to a gym, an indoor restaurant, or big, crowded events like rallies, concerts, nightclubs, etc.”

What would she feel comfortable doing? “I might dine outside, if the tables were spaced apart, and I felt like the customers and restaurant staff were taking precautions.” Just this past week, she went camping with her family, but she chose campgrounds following CDC guidelines. “For other places, like parks and beaches, my advice is to be prepared to leave if they get crowded and you cannot safely distance,” she says.

For his part, Kucharski cites the simple guidelines Japan has put out: avoid, when at all possible, the “3 Cs” — closed environments, crowded places, and close-contact settings.

And it’s a reminder that large, entirely optional indoor events, like political campaign rallies (for any candidate), seem exceptionally dangerous right now — not just for those who attend, but also for those they might come into contact with later.

Katherine Harmon Courage is a freelance science journalist and author of Cultured and Octopus! Find her on Twitter at @KHCourage.

Support Vox’s explanatory journalism

Every day at Vox, we aim to answer your most important questions and provide you, and our audience around the world, with information that has the power to save lives. Our mission has never been more vital than it is in this moment: to empower you through understanding. Vox’s work is reaching more people than ever, but our distinctive brand of explanatory journalism takes resources — particularly during a pandemic and an economic downturn. Your financial contribution will not constitute a donation, but it will enable our staff to continue to offer free articles, videos, and podcasts at the quality and volume that this moment requires. Please consider making a contribution to Vox today.

Author: Katherine Harmon Courage

Read More