And the rest of the week’s best writing on books and related subjects.

Welcome to Vox’s weekly book link roundup, a curated selection of the internet’s best writing on books and related subjects. Here’s the best the web has to offer for the week of March 8, 2020.

- The novel coronavirus is reshaping the world, and publishing along with it. Publishers Weekly has a list of all canceled and postponed literary events, plus the policy changes that publishers are making to cope with social distancing.

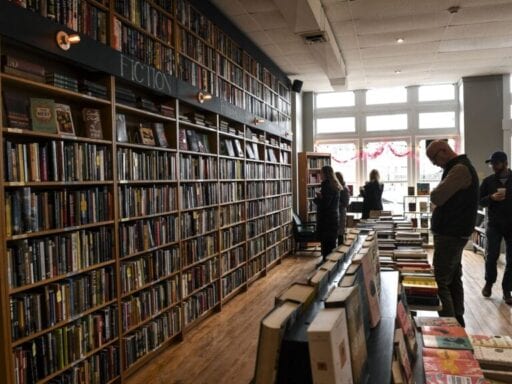

- At Slate, Laurie Swift Raisys tells us what it’s like to run an indie bookstore while everyone is staying inside:

It was the start of last week when the store just kind of became a ghost town. We live on Mercer Island, which is a town of 20,000 people. On days when we would usually have people coming in the store, we had no one. Hours would go by where maybe one person would come in, and it was a little bit frightening. As a business owner, you rely on the community and the people that come in and shop at your store in order to pay your bills and pay your employees. Last week was incredibly stressful, and this week has been very stressful, and I don’t really see an end in sight right now.

- If you’re concerned about your local indie, Josh Cook has a list of ways to support it safely at Publishers Weekly:

You know that book you want that’s coming out in August? September? Ordering it during a downturn doesn’t cost you any more than you planned to spend, and paying now gives the store cash when they need it.

- Meanwhile, books you should not buy: Amazon has been flooded with dubious and often plagiarized self-published books about the coronavirus, the Guardian reports.

- And at Slate, Ben Cohen explains how the plague influenced Shakespeare’s work:

Shakespeare ran hot and cold. His plays were not spread over the course of his career. They were clustered. “Once you start seeing those plays are really bunched, you start asking: Well, what accounts for a lot of plays in a very short period of time?” Shapiro says.

It was the oddest bit of circumstance in this case: a plague year. The plague closed London’s playhouses and forced Shakespeare’s acting company, the King’s Men, to get creative about performances. As they traveled the English countryside, stopping in rural towns that had not been stricken by the plague, Shakespeare felt that writing was a better use of his time.

- But there are also things that exist outside of the coronavirus realm. This week, Netflix has announced the cast of its forthcoming Baby-Sitters Club adaptation, and Seventeen has the photos. It looks like the series is reimagining Dawn away from her California girl florals into something funkier, but everyone else’s costumes are exactly the way you’d picture them from the books. Honestly, nothing else has brought me as much joy this week as this Claudia Kishi realness.

- At the Guardian, Peter Swanson trawls the pages of detective fiction for a few perfect murders:

What did I learn from making this list? That perfect murders, at least the artful kind we find in books, are all about concealment and misdirection. They have a lot in common with well-executed magic: it’s all about fooling the detectives (and the readers), making us look away from where the crime is happening. Agatha Christie’s The ABC Murders, another book on Malcolm’s list, is a textbook example: it appears as though a psychopath is bumping off victims according to the initials of their names, but the truth is something else altogether. Poirot, naturally, is not misled, and the world can be set to rights.

- At the Outline, Maris Kreizman — always required reading — explains why Hachette’s decision to cancel Woody Allen’s memoir was not censorship:

In an age in which bothsidesism in publishing has lended credence to climate-change deniers and conspiracy theorists, it’s time to admit that agendas have changed, especially when fact checking is not a built-in part of the editorial process. Books that may be commercially viable are not necessarily good simply because there is an audience for them (the French edition of Allen’s memoir will be published as planned). In an industry that is built upon the backs of young women, it’s infuriating that publishers haven’t seemed to care about denigrating the very people who work on their big books.

- The My Dark Vanessa conversation continues. At BuzzFeed News, Anne Helen Petersen profiles author Kate Elizabeth Russell:

“Whatever, and however, anyone wants to respond to Vanessa, I think it’s valid,” Russell told me. “Any reaction is valid. There are some that I might agree with more than others, but this book is an offering to readers. Everything in it is an offering.

“I had to write it in a way that would make that possible,” she continued. “Which means it had to be fiction. It had to be artifice. Because otherwise — how could I stand it?”

- At the Baffler, Jess Bergman analyzes the cool girl literary trend of the moment: books about alienated young women.

With this literature of relentless detachment, we seem to have arrived at the inverse of what James Wood famously called “hysterical realism,” describing a strain of fiction overflowing with eccentric characters and detail that, in its exaggerated vitality, depicts life as “fervid intensity of connectedness.” What these novels constitute instead is a kind of denuded realism. Rather than an excess of intimacy, there is a lack; rather than overly ornamental character sketches, there are half-finished ones. Personality languishes, and desire has been almost completely erased—except, of course, the desire for nothing. (“I wanted Klonopin,” Moshfegh’s narrator thinks. “I wanted Xanax.”)

- At The Cut, Matthew Schneier profiles the luxury publishing company Assouline. LOL, rich people:

The Assoulines do not carry themselves like inky publishers. They are charming, courtly, Fronch, living and working surrounded by art, fine cigars, and bourgeois-bohemian eclectic. Their office conference room is an homage to Seville, their favorite vacation destination, and is decorated with art and antiques from their pilgrimages there. Their stores once sold a scented candle meant to smell like cocaine. “I learned a lot about the theater of doing business” from them, says Richard Christiansen, who previously worked for Prosper as a creative director. “The importance of walking into an office, opening the door, and gasping because it’s so beautiful.” (He once learned the hard way not to sneak wine out of the boss’s office while burning the midnight oil; it cost a small fortune to replace the bottle.)

- Alexandra Styron is the daughter of William Styron, the white, gentile man who wrote Sophie’s Choice and The Confessions of Nat Turner. At the Atlantic, she remembers the debate over whether her father’s novels were works of cultural appropriation:

To say my father was pained by the experience would be an understatement. He went forth gamely at first, confident that he could defuse the situation simply by explaining his motives. He was a novelist, not a historian, with an intention to transcend facts in the interest of thematic weight and moral inquiry. But the anger he encountered was unrelenting, reflecting a national mood that went well beyond the parameters of bookstore chitchat. Even the ironic commentary was too hot to touch—at a panel in New Haven, a black man dressed down my father, then said to his companion, “Man, I wish LeRoi Jones had written that book!”

- At Wealthsimple, the great Karen Russell thinks through writing, motherhood, time, and money:

A secret hope of mine, which I now find hilarious: I imagined that once I had a child, I would become a faster writer. Faster, and also better. It’s hard for me to reconstruct the optimistic logic that led me to this hypothesis. I think I honestly believed that if I did not have the option to write badly, I would simply evolve, like that Lamarckian giraffe, into a more efficient creature. Instead, for a long time after my son’s birth, I stumbled through a hormonal fog. We still aren’t sleeping much in this house. Many days, I feel like my mind has become one of those crane hands you see at arcades and truck stops, grasping arthritically at the air above the sunken prizes.

And here’s the week in books at Vox:

- The coronavirus pandemic is a reminder of how much we need each other

- I called out American Dirt’s racism. I won’t be silenced.

- If God is dead, then … socialism?

As always, you can keep up with all our books coverage by visiting vox.com/books. Happy reading!

Author: Constance Grady

Read More