The Bay Area has shut down. Can it buy us the time we need?

Monday afternoon, I took the baby to the park. He is too little to appreciate it. He mostly stares at me, unless the sun is in his eyes, in which case he closes them. We go to the park for my sake. I like feeling like the kind of normal person who goes to the park with a baby and is not living in the middle of the apocalypse.

That same afternoon, six counties that make up the San Francisco Bay Area declared that their 6 million residents would, effective at midnight, be subject to a “shelter-in-place” law that bans nonessential activities and gatherings. Most businesses have shut down, except the ones that do the work necessary to keep society running, and essentially all leisure activities involving other people are now illegal. Grocery trips and trips for medical care and essential household supplies are allowed. Going over to your friend’s house is a misdemeanor. It’s one step short of a lockdown.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19819365/koios.jpg) Courtesy of Kelsey Piper

Courtesy of Kelsey PiperNo one really knows how this will end. The “shelter-in-place” law is for three weeks, through April 7, though the counties warn they might extend or shorten it, based on the facts on the ground. On Thursday night, California Gov. Gavin Newsom announced that a similar order will be put in place for the entire state. That order is in place “until further notice.”

In the meantime, the bookstore at the end of my block is now closed. Schools are closed. Most offices are closed. Bars are closed. Restaurants are only allowed to serve takeout.

I’d been avoiding those places for weeks now anyway, trying to do my part to slow down the spread of the coronavirus. But things I hadn’t been avoiding are banned now, too, like having a friend over for dinner, or meeting a friend at a trailhead for a hike. My roommate who is a nanny scanned the rules desperately trying to figure out if her job was prohibited. (Answer: child care for people doing essential work is permitted.) Sitting in the grass at this park with the baby would be permitted, as long as we didn’t come within six feet of anyone in the course of getting there. I suspect, nonetheless, it’ll be our last trip for a while.

The San Francisco Bay Area is the first place in the US to pass a shelter-in-place law to address the coronavirus pandemic. And it won’t be the last. Mayor Bill de Blasio has warned New Yorkers that they should expect one soon.

At least they get a warning — for us in the Bay Area, the Monday announcement was a complete shock. County and city websites buckled under a sudden surge in traffic. The San Francisco Chronicle says that as the news broke, 1 percent of the 6.3 million people in the Bay Area were reading their article explaining the orders.

We spent Monday night scrambling. A roommate’s boyfriend lives alone, and would be prohibited from all human contact for the three weeks as the rules are written. And it might be longer. But if we move him in by midnight, that’s allowed, right? Another roommate’s boyfriend cancels a visit. Two friends come by for a last hug. One of them lives alone, too. Will he be okay? Depends on how long it is.

We’re not angry at the county government. We’re proud of them, mostly. We’re stressed, scared, and uncertain, but optimistic we can stem the growth in case numbers before our medical system is overwhelmed like other medical systems have been. We’re hoping our community’s doctors and nurses won’t collapse on their feet from too many 24-hour shifts if these measures are sufficient. They have to be. Right?

Life under the new law

Midnight arrives.

We’re “sheltering in place” now.

It’s weird how much being locked down feels different from staying home voluntarily. We’d decided weeks ago we should avoid others, do our part in preventing this pandemic from overrunning hospitals. But now that it’s required, it’s stressful.

It’s even more stressful to imagine what will have to happen if these measures aren’t sufficient. It might be years before things can return to normal.

On Tuesday morning I went out for a walk to look at my city under “shelter-in-place.” The walk is permitted as long as I don’t go within six feet of anyone. “It is a crime (a misdemeanor) not to follow the Order (although the intent is not for anyone to get into trouble)”, says the FAQ from my county.

The sidewalks aren’t six feet wide; I think I am technically committing a crime when my neighbor walks past me, walking his dog.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19819378/Image_from_iOS__1_.jpg) Courtesy of Kelsey Piper

Courtesy of Kelsey PiperThe park, which is usually full of children, has only two. There are people about, but not many. Aside from the bookstore, the stores nearby generally fall under the “essential business” category — laundromats, convenience stores, gas stations, Subway, a dry cleaning place. They’re open but empty. It’s unclear what percentage of businesses count as “essential.”

Meanwhile, there is not a whiff of enforcement. The police department in my city, Oakland, is understaffed and has been facing unrelated tumult. If enforcement is needed, I suspect it’ll have to be the National Guard. It’s a terrifying thought, even though I know they’re on our side.

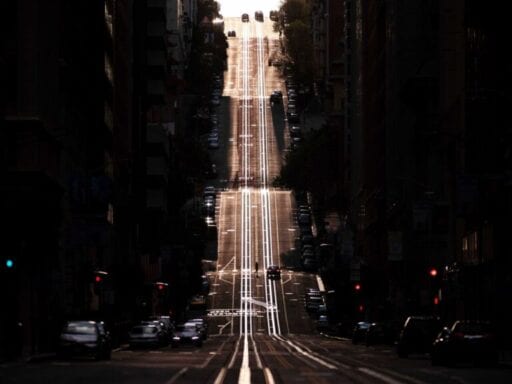

The streets aren’t empty, but they’re quieter than usual. A friend posts an image from Google Maps of traffic congestion in the Bay, the highways usually a nightmarish red at rush hour and not much better the rest of the time. “‘bay area all in green for st. patrick’s day,” she writes.

Nonessential employees should be home. Reality is more complicated.

Hours before we are to shelter in place, some friends get emails claiming that their employers are essential services and that employees must show up to work. A friend works for an enormous conglomerate whose health care department makes coronavirus tests — definitely essential services. But his office of about 80 people works on something completely different. “Colleagues are expected to report for their regular shifts,” the company emailed him.

The Bay Area is full of tech companies like this where it is questionable whose services within them are essential. Elon Musk emails Tesla employees to tell them that the factory will remain open. He says it’s “totally ok” if they want to stay home (though their supervisors clarified they’ll have to use their sick or vacation time). Musk thinks the coronavirus panic is overblown. Why’s Tesla an essential service when so many other companies are not? (In fact, the county told Tesla it was not an essential service, and the company has now said that it will shut down on Monday. Tesla did not respond to a request for comment from Vox.)

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19819430/GettyImages_1008732800.jpg) Mason Trinca for The Washington Post via Getty Images

Mason Trinca for The Washington Post via Getty ImagesBecause there is so little clarity, people on Facebook are asking each other what’s allowed and what isn’t, and sharing advice about the process for wrongful termination claims if someone is fired for trying to get their company to take the orders seriously.

There’s a sense of patriotism, of courage, of civic duty, but it’s stifled and poorly directed. We want to serve our country, but we don’t know how. We want to save our neighbors, but we don’t know how. On many of the most critical questions, the experts don’t know either.

I try to imagine our county officials, facing immense human suffering from the shutdown and immense human suffering from the pandemic, trying to figure out which tragedy would be the smaller tragedy once all the bodies are counted. I’d expected them to be paralyzed by the decision and default to inaction. They didn’t do that, and I’m grateful.

Fighting to flatten the curve

I check Bay Area coronavirus cases. Even if the shelter-in-place order works perfectly, the numbers won’t start declining yet. Italy’s lockdown happened on March 9. New cases continued to surge for five or six days — the average incubation period of the virus. Now, a week later, new case numbers seem to be flattening. Maybe we can pull off the same thing before our hospitals are overwhelmed. (As of Thursday, there are 51 new cases in the Bay Area.)

My friend with cancer has her doctor’s permission to take out her own sutures from her recent surgery, if hospitals get overwhelmed. But maybe they won’t. Maybe we can extinguish this thing. California has a population similar to that of South Korea. Perhaps we can turn things around like they did.

There is so much we don’t know about this virus and the situation it has put us in. We don’t know how many cases are asymptomatic. We don’t know how many people in the US have the virus but haven’t been tested yet. We don’t know if people who have recovered already have immunity at all, or how long it lasts if they do. There are so many unknowns that ought to shape our response and change what tradeoffs we’re willing to make.

On Tuesday, Stanford School of Medicine’s John Ioannidis (who is, I assume, under shelter-in-place restrictions, too) argued that since we know so little, we should hesitate with such drastic restrictions. I disagree. With this order, we have bought ourselves three weeks. In three weeks we’ll know more. Some of these terrifying uncertainties will have resolved themselves into information we can use to keep our communities safe. And we’ll have manufactured more medical devices and protective equipment that can keep sick people alive and doctors and nurses safe.

We might be able to stop the virus in its tracks, for now, and give our world time to figure out its next steps.

I can’t pretend that it’s comfortable or secure or reassuring here in the Bay in this moment — but I hope that the rest of the country is ready to follow us.

Sign up for the Future Perfect newsletter and we’ll send you a roundup of ideas and solutions for tackling the world’s biggest challenges — and how to get better at doing good.

Future Perfect is funded in part by individual contributions, grants, and sponsorships. Learn more here.

Author: Kelsey Piper

Read More